Translating terrorism is tricky. Russian director Kirill Serebrennikov’s The Student is an adaptation of a play by the German writer Marius von Mayenburg which was staged in London two years ago under its original title, Martyr. One exchange in this story (which is set in and around a school) references what might happen if Christian extremists pursued their beliefs with a fervour we associate more with militant Islam. The two concepts don’t quite combine in English as they did in Russian, which used the title (M)Uchennik, a play on the two words which caught the associations of both.

Serebrennikov is known in his homeland as much as a stage director as for his film work – The Student is his sixth feature, and premiered at Cannes last year – and he first staged the play at the theatre which he runs in Moscow (casting partly repeats). He has not only adapted the work for screen, but clearly shaped the German original into a Russian context, most notably that of the Orthodox religion. It gives a sharp accent to an issue – the relation between state and Church, of concurrent official ideologies – that has become particularly acute in Russia this century.

Exact references, to both Old and New Testament, appear as screen titles

All of which makes the film’s teenage protagonist Venya (Pyotr Skvortsov, sulkily intense, main picture) something of a contradiction. His adolescent rebellion, against both his mother and the school authorities, can’t be dismissed in the usual way because his protests are on fundamentalist religious grounds, and he cites the Bible, chapter and verse, to prove his points (exact references, to both Old and New Testament, appear as screen titles).

His single mother (Julia Aug), perpetually exhausted and working in three jobs, clearly loves him, but doesn’t have a clue what to do with a son who’s become practically a stranger (a normal teenager, in her book, would be “collecting stamps and jerking off all the time”). More enterprising is the approach taken by the school’s progressive biology teacher Elena (Victoria Isakova, giving a highly intelligent performance; pictured, below, left, with Julia Aug, right), who sees Venya’s stubbornness as some sort of cry for help, and initially tries to approach him more sympathetically.

But the dynamic between the two moves towards conflict. When she teaches sex education – including information about homosexuality, another highly sensitive issue in Russia these days – he strips naked and rampages around the classroom, meeting her explanations about contraception with fire-and-brimstone injunctions to “be fruitful and replenish the earth”. Lessons about Darwinism are countered by his dressing in a guerrilla costume and preaching creationism.

But the dynamic between the two moves towards conflict. When she teaches sex education – including information about homosexuality, another highly sensitive issue in Russia these days – he strips naked and rampages around the classroom, meeting her explanations about contraception with fire-and-brimstone injunctions to “be fruitful and replenish the earth”. Lessons about Darwinism are countered by his dressing in a guerrilla costume and preaching creationism.

Even the priest who is attached to the school is defeated by the phenomenon, his attempts to co-opt the teenager into the official structures of religion countered by accusations about the Church’s venality, its attachment to palaces and Mercedes rather than its duty to “bring fire to the earth”. The things notably lacking in Venya’s worldview, however, are charity and love, highlighted particularly in his interaction with Grisha (Alexander Gorchilin, pictured below with Skvortsov), the bullied outcast of the class who latches on to his charismatic contemporary for his own reasons.

Venya sees Grisha not as a friend but almost as a disciple (which was, in fact, an alternative title for the film). Grisha has one leg shorter than the other, so Venya doesn’t hesitate to call him a cripple (Christ, we are reminded, sought out the cripples and the outcasts). Trying to extend the shorter leg becomes something of a ritual test of faith, as Venya intones “Grow, leg” over his companion’s half-naked torso; for the other boy, hands and half-naked torsos hint at something else altogether. The disillusionment will be painful.

Scenes like that reveal that The Student has plenty of very dark comedy, although you’d need an audience on the right wavelength to extract it (and some may well be lost in translation). The antics of the school’s headmistress and some of her proteges are conveyed with a pronounced degree of satire. Serebrennikov’s first significant feature, Playing the Victim, from a decade ago, another adaptation from the stage, also had a central figure who didn’t fit into the world around him, and was also gloriously rich in black comedy – but the mood in his new work is somehow darker, more desperate.

Scenes like that reveal that The Student has plenty of very dark comedy, although you’d need an audience on the right wavelength to extract it (and some may well be lost in translation). The antics of the school’s headmistress and some of her proteges are conveyed with a pronounced degree of satire. Serebrennikov’s first significant feature, Playing the Victim, from a decade ago, another adaptation from the stage, also had a central figure who didn’t fit into the world around him, and was also gloriously rich in black comedy – but the mood in his new work is somehow darker, more desperate.

It’s felt especially in a very uneasy score from composer Ilya Demutsky, which uses strained, sometimes atonal string writing to intersperse episodes and set the emotional tone (it’s much more nuanced than repeated closing use of Slovenian heavy-metallers Laibach’s anthem “God Is God”). There’s something somehow detached to Vladislav Opelyants’ cinematography, too, working largely with long shots and controlling colour and light impeccably. Filmed in Kaliningrad, Russia’s enclave on the Baltic, there’s virtually nothing that identifies the location as specifically Russian – rather it’s a somehow generalised small-town atmosphere, visually interchangeable perhaps for Scandinavia or other coastal northern climes.

That quality – of being very Russian in spirit, while presenting an environment that in itself is not distinctly Russian at all – could not help but recall Andrei Zvyagintsev, especially his first film, The Return. And comparisons for The Student are also appropriate with Zvyagintsev’s latest, Leviathan. Both films are saying that something is somehow very much not right in the society in which they are set, but whereas Leviathan unfolded on an almost epic scale, Serebrennikov’s film speaks in a more minor key, its dramatic action more muted (and its script, arguably, on the wordy side). The Student doesn’t make wide assertions about morality, instead it probes – teases, even – around issues of values (religion being, after all, among the deepest of all). It’s an uneasy film, one that leaves a somehow bitter taste behind.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for The Student

That means he hardly knows his younger sister Suzanne (Léa Seydoux) at all, and is meeting sister-in-law Catherine (Marion Cotillard) for the first time, though she and her husband Antoine (Vincent Cassel) have named one of their children after him. These two female characters are the ones that come closest to him: Cotillard’s character is especially sensitive, as she instinctively understands the issue – even if her words “Combien de temps?” lose much of their acuity in translation – that does finally remain unspoken.

That means he hardly knows his younger sister Suzanne (Léa Seydoux) at all, and is meeting sister-in-law Catherine (Marion Cotillard) for the first time, though she and her husband Antoine (Vincent Cassel) have named one of their children after him. These two female characters are the ones that come closest to him: Cotillard’s character is especially sensitive, as she instinctively understands the issue – even if her words “Combien de temps?” lose much of their acuity in translation – that does finally remain unspoken. Nathalie Baye plays Martine, the matriarch. Though it’s the entire family that is on the edge of a nervous breakdown, we certainly sense where it came from. Dolan has a record of harping on mothers – his debut film was titled I Killed My Mother, his most recent one just Mommy – but actually that isn’t the dominating relationship here, rather it’s the whole entity that is under cruel scrutiny. (Nathalie Baye with Gaspard Ulliel, pictured above right.)

Nathalie Baye plays Martine, the matriarch. Though it’s the entire family that is on the edge of a nervous breakdown, we certainly sense where it came from. Dolan has a record of harping on mothers – his debut film was titled I Killed My Mother, his most recent one just Mommy – but actually that isn’t the dominating relationship here, rather it’s the whole entity that is under cruel scrutiny. (Nathalie Baye with Gaspard Ulliel, pictured above right.)

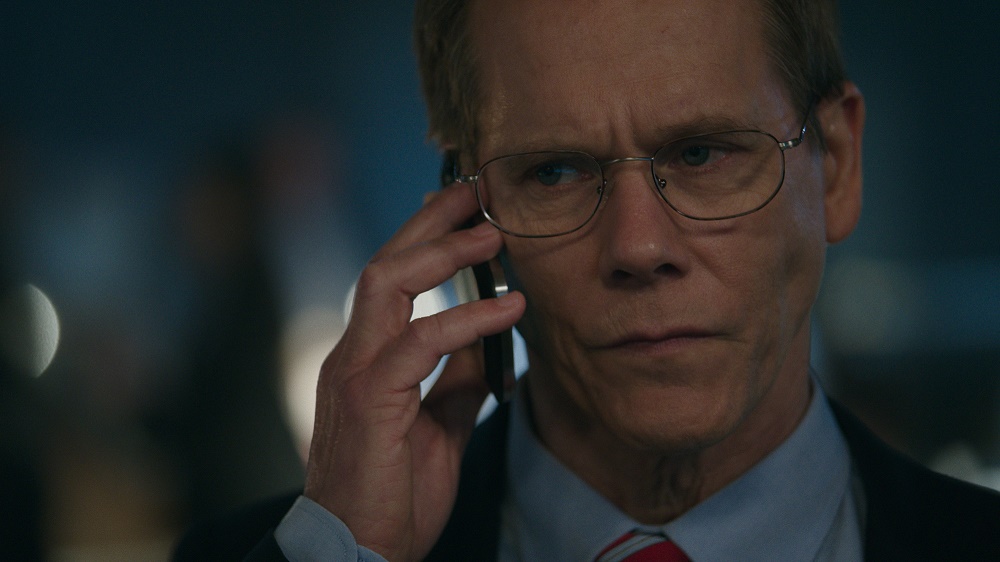

The script also chooses to zoom in on the domestic lives of the Tsarnaev brothers, the perpetrators of the atrocity. The older brother Tamerlan has a wife and a small child, and is clearly of a more ideological bent. “[Martin Luther] King was a fornicator,” he sneers. “But I’m a fornicator,” reasons his doubting kid brother Dzhokhar, who has a penchant for videogames and fast cars. But the main focus, the glue holding the centre together, is fictional police sergeant Tommy Saunders (

The script also chooses to zoom in on the domestic lives of the Tsarnaev brothers, the perpetrators of the atrocity. The older brother Tamerlan has a wife and a small child, and is clearly of a more ideological bent. “[Martin Luther] King was a fornicator,” he sneers. “But I’m a fornicator,” reasons his doubting kid brother Dzhokhar, who has a penchant for videogames and fast cars. But the main focus, the glue holding the centre together, is fictional police sergeant Tommy Saunders ( Director Peter Berg licks the story along at an efficient pace, imparts a powerful sense of a city under siege in the overhead camerawork, and wrings tears in a final reveal involving the actual participants. Dramatically, though, for all the immense effort of the manhunt, not quite enough is at stake in Patriots Day. There is some alpha dog dick-waving between the FBI and John Goodman's police commissioner (“this is my fucking city,” he hollers). And that's about it.

Director Peter Berg licks the story along at an efficient pace, imparts a powerful sense of a city under siege in the overhead camerawork, and wrings tears in a final reveal involving the actual participants. Dramatically, though, for all the immense effort of the manhunt, not quite enough is at stake in Patriots Day. There is some alpha dog dick-waving between the FBI and John Goodman's police commissioner (“this is my fucking city,” he hollers). And that's about it.

While Katherine makes herself increasingly crucial to an initially hostile set of colleagues

While Katherine makes herself increasingly crucial to an initially hostile set of colleagues

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe).

It’s not only physical slightness that sets Chiron apart: he’s treated as an outsider by his more aggressive contemporaries for another reason, one which they sense but he himself has not yet registered. The film opens with the latest of what we guess is a series of rejections, but this one ends on a more positive note with Little befriended by Juan (Mahershala Ali). Of Cuban descent, Juan may be a community hard man and drug dealer, but he shows only kindness to this resolutely silent youngster, first feeding him and then taking him home to his girlfriend Teresa (Janelle Monáe). The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.

The defining moment of the succeeding section also takes place at the sea, as Chiron and Kevin talk on the beach (pictured above, Jharrel Jerome, left, with Ashton Sanders): Chiron once more risks trust, relaxing the barriers of self-protection that he has constructed around himself (“I cry so much sometimes I might turn to drops”, he poignantly reveals). The cruelty is that hurt will again follow revelation, culminating in an act of self-assertion that will change the course of the young man’s life, sending him away from his home environment.