If one were to stop at the title, My Life as a Courgette – from the French Ma vie de Courgette and unsurprisingly renamed for those insular Americans as My Life As a Zucchini – could be too easily dismissed as a juvenile or childlike frivolity. And that would be to under-estimate this French-Swiss, Oscar-nominated, stop-motion animation, which is one of the more profound, touching and daring family films of recent years.

Based on the French novel Autobiography of a Courgette by Gilles Paris, it follows the fortunes of a nine-year-old boy, Icare, nicknamed Courgette by his alcoholic mother, maliciously or not we’ll never know since the film opens with the lonely lad accidentally killing his single parent, while playing with one of her empty beer cans.

When Courgette is sent to an orphanage, where he meets the fellow victims of a variety of social problems – drug addiction, mental illness, crime, child abuse and deportation – the story seems primed for the usual descent into state-sponsored despair. But just for once these kids are in safe hands.

The film’s Swiss first-time director, Claude Barras, studied illustration with the intention of becoming an illustrator for children’s books, but changed course when he met and was trained by the animator Georges Schwizgebel. He then teamed with the Belgian writer/director Cédric Louis, with whom he made a number of short animations.

Barras’s screenwriter for Courgette, Frenchwoman Céline Sciamma, already has a formidable reputation as a writer/director of three feature films, the perceptive, atypical coming-of-age dramas Water Lilies, Tomboy and Girlhood.

The pair spoke to theartsdesk about their collaboration.

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: Gilles Paris’s book was aimed at adults. Why did you decide to broaden the audience, and turn this tough subject into a family film.

CLAUDE BARRAS: To be completely honest, my producers said that if we made the film only for adults we would have a hard time finding the financing. At the same time, I had noticed that there was not much diversity in children’s films, which are mainly about entertainment. Maybe we think we need to constantly entertain children, because we’re ashamed of the world we’re offering them. But since I love Ken Loach’s films and the Dardennes brothers' films, I thought perhaps I could make a social realist film for children.

The main subject is violence, so it’s important to talk about violence and show what the children have been confronted by. It’s a delicate subject for kids, but it’s something they are confronted by in everyday life – in the playground at school, what they see on television and on the internet. And I thought that to tell a story that breaks this chain of violence, and brings hope, was a beautiful thing to try to do.

CÉLINE SCIAMMA: Claude was always telling me it’s "Ken Loach for kids".

Ken Loach doesn’t hold back from criticising the state. But I understand that the film is lighter than the book, less critical of the childcare system in France.

SCIAMMA: I don’t know about less critical, because the book was also a tribute to social workers. And social workers have said about the film that yes, this is how it is in an ideal way, when the system works it can be like that. We’re not making a fantasy world. And each of the kids in the film has a profile that is very harsh, yet true, all kinds of abuses are being represented. So we’re not being shy.

BARRAS: In cinema orphanages are typically depicted as places of abuse, and the outside world as that of freedom, for example in The 400 Blows, or The Chorus. In My Life As a Courgette that pattern has been reversed: abuse is suffered in the outside world and the orphanage is a place encouraging appeasement and reconstruction. After some time immersed in a foster care centre, I realised the importance of treating the theme with great care, because the homeis at the heart of the relationship that these children, who have been lacking in affection, maintain with the adult world.

Presumably a key challenge was to take this initially bleak material and present it in a way that wouldn’t disturb or confuse young audiences?

SCIAMMA: It was all about the beginning of the film – because at the beginning you have to kill the mother and make a point about the boy’s social background. I didn’t continue with the writing until I found a way to do that. When I had the idea of this little kid playing a game with empty beer cans, I realised ‘this is the film’.

It’s about synthesising emotions, avoiding contrasts. For instance, if you take a strong narrative in animation, like The Lion King, there are these very sad scenes – with that film around the death of the father – and then scenes with kind, funny animals. We didn’t work that way, a light scene and a heavy scene. Our narrative is about telling all the emotions at the same time.

Almost treating the young kids as grown ups?

SCIAMMA: Of course. The goal of the film was to take children very seriously as characters, in the writing, and to take children very seriously as an audience, believing in their intelligence.

What did you want youngsters to get out of it?

SCIAMMA: A sense of solidarity. It’s a movie about friendship, I think it’s a tribute to tolerance, to being welcoming, which is quite an issue today. It’s about how you can love and be loved, even when you’ve had a very wrong start in life. It’s also about what a family is, or can be, how we bond.

How did you get together on this?

BARRAS: I read the book 10 years ago and fell in love with it. There was a six-year period in which I was developing the idea, while working on other projects. After these six years I met a producer who agreed to do the project, then the producer put me in contact with Céline. I’d just seen Tomboy (pictured below) a few months before, and so was immediately enthusiastic.

In the book there are 20 children and I chose seven to tell the story. But I’m not a scriptwriter. I’d written a first version, then gave Céline entire freedom to do what she wanted. She kept some ideas, but simplified the story, made sure that each of the children had some time, added subtleties. Céline knew how to strike the right balance between humour and emotion, adventure and social realism.

SCIAMMA: Reading Claude’s first draft and the book I felt a strong connection between my work and this material, because it’s not just about youth, but youth at the margin. And there’s a strong social context to it, you can still be political and make propositions.

Claude, are you principally the director, or also one of the animators?

BARRAS: I do practice animation sometimes, but I’m not very good at it. My main role is director and character design.

So how did you set about the character design for this? Does it reflect previous work?

BARRAS: I’ve collaborated in the past with an illustrator, Albertine, who makes very joyful work, very colourful. I also did all this work with Cédric Louis which is more similar to what Tim Burton does, the dark aspect of his design. But Tim Burton’s films have a lot of fantasy in them, whereas, as I said, I think my film is closer to social realism. Another source of inspiration is Nick Park’s Creature Comforts, which is a masterpiece. I see in Courgette a mix of all these different elements.

What to do think the choice of stop animation lends to the storytelling?

BARRAS: I think it’s extremely simple and easy to convey emotions to the audience with this form. It’s both easy for the viewer to see the expression changing and for the animator who’s manipulating the puppets, who can change the whole expression with one move.

These faces remind me of emoticons. I think they balance a very realistic, tough story, bring some softness to it and perhaps some hope.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for My Life as a Courgette

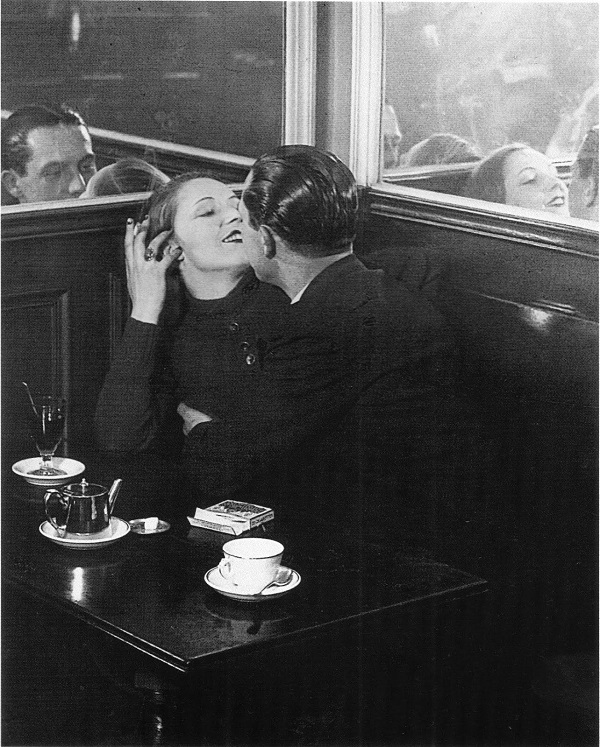

Brassaï: Lovers in a Café on the Place d'Italie, Paris (1932)

Brassaï: Lovers in a Café on the Place d'Italie, Paris (1932) Constantin Brancusi: The Kiss (1916)

Constantin Brancusi: The Kiss (1916)