Watching Matthew Holness’ debut feature Possum, you’d be forgiven in thinking he was a tortured soul. Lead character Phillip (played by Sean Harris, pictured below) is a lean marionette of a man, prone to horrific flights of fantasy involving a human-headed spider puppet.

French director Michel Hazanavicius made a name for himself with his OSS 117 spy spoofs, Nest of Spies (2006) and Lost in Rio (2009), set in the Fifties and Sixties respectively and starring Jean Dujardin as a somewhat idiotic and prejudiced secret agent. But it was with The Artist in 2011 that he hit the jackpot, marrying his gift for period recreation with a story of genuine depth and warmth.

Very early in his career, Andrew Haigh worked as an assistant editor on such Ridley Scott blockbusters as Gladiator and Black Hawk Down. He didn't actually meet Scott in person until years later, when the eminent director had no recollection of him.

It’s about time Juliette Binoche and Claire Denis teamed up: the legendary French actress, Gallic film royalty known by her countrymen and women as La Binoche, with one of the country’s most unique directors, both talented and formidable women who have very much forged their own paths in the cutthroat world of the film industry.

Just like waiting for a bus, there are now two collaborations between them, made in quick succession: the second, a science fiction co-starring Robert Pattinson, is in post-production. The Arts Desk met Binoche in Paris to speak about the first.

Let the Sunshine In has the ring of schmaltzy romcom or some feel-good, self-help musical; it hardly bodes well. And yet this is Denis (pictured below), whose work – Chocolat, Beau Travail, White Material, 35 Shots of Rum, the aptly named Bastards – doesn’t dabble in popcorn frivolity, but tangible, often painful reality; even her vampire film Trouble Every Day had the disturbing stench of believability.

Thus the new film, which involves a middle-aged, divorced artist, Isabelle (Binoche), and her desperate search for ‘one real love’. Through the course of the movie she considers numerous suitors, each clearly unsuitable, at least two of them married, Isabelle throwing her heart, soul and body at them, with humiliation and disappointment the reward. Though she has a 10-year-old daughter, we see the girl onscreen just once, as she’s driven away by her father. Isabelle’s focus is herself and her fear that her love life is behind her; and for someone who is seemingly successful and intelligent, and old enough to know better, she’s rather foolish about it all.

With its romantic theme, Let the Sunshine In is closest to Denis’ Vendredi Soir, an offbeat, touching love story involving a man and a woman who meet in a traffic jam. But the new film is edgier, more pessimistic and, actually, funnier. Denis has co-written the script with the French author Christine Angot, and the pair are so on the money in their characterisations and situations that the result is variously sad, discomforting and enjoyably ridiculous, with Isabelle and her amours equal targets; the writers also shoot a few well-aimed arrows at the pomposity of the Parisian art world. Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

Denis has surrounded her star with some accomplished male foils, not least Gérard Depardieu as a clairvoyant to whom Isabelle turns in the film’s wondrously bonkers final scene. This is another first, since the pair haven’t acted together before, the encounter lent added spice by the knowledge of Depardieu’s unsolicited criticism of Binoche in 2010, when he told a journalist: “I would really like to know why she has been so esteemed for so many years. She has nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

She shows plenty opposite him, but that’s no surprise. And this is Binoche’s show. Gaudily dressed in mini-skirt and leather boots, her make up overdone, invariably on the verge of welling up, her Isabelle teeters on the edge of nonsense. Yet Binoche also reveals shards of integrity, intelligence, passion and some self-deprecating humour in her character. Despite her spectacular signature laugh, the actress has done relatively little comedy, though this confirms a gift for it.

The suggestion is of a full-blooded individual thrown off-kilter by romantic panic. It’s a raw, real, winning performance, in an off-beat, female-centred film, talky in that way that many failing relationships are, and speaking quite boldly about the problems that women of a certain age may have to find love, or at least a half-decent male companion. DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this?

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: What attracted you to this?

JULIETTE BINOCHE: I know something about the difficulty of love. I was touched by the writing, because it's rare to have a script that is so well-written, which feels real. And it was my first time with Claire Denis. To have the complicity of those two women, Claire and Christine, putting together those fragments of love, was very appealing.

But we didn't know it was going to be that funny. When I saw the film the first time people were laughing a lot, and I was laughing as well. The second time I saw it I was crying. The film can be taken very differently. It depends how you feel, what kind of distance you have.

Why do you think the character is so unlucky in love?

I think she's trying to find a solution outside of herself, for her lack of love, her need, which is what we all tend to do. What I've learned going through life is that you've got to find some place in you that is at peace, first, in order to then attempt a relationship. But it takes courage. And it takes time also.

I don't believe that suddenly everything is resolved because you're in a couple. When I was a young lover I thought you really had to meet your alter ego, the other part of yourself. Now I don't think that exists. True love, the one that stays forever, is in you. It takes a while to understand that. That's why you suffer so much. When you're not expecting everything from the other person, then I think that things can happen, in a different way.

The film also touches on the way that social differences can affect relationships.

That's a big question, and not an easy one. Can love survive social differences? It’s a very important subject to the writer, Christine. She had been through that kind of situation. So what she writes about it is very explored, lived, and I felt that in the writing. For the man who I meet when dancing, Claire decided to cast Paul Blaine, because he was more fragile in a way, and that was very intelligent. I felt the difference somehow. It brings something special to the film.

What did you bring of yourself to this character?

Everything.

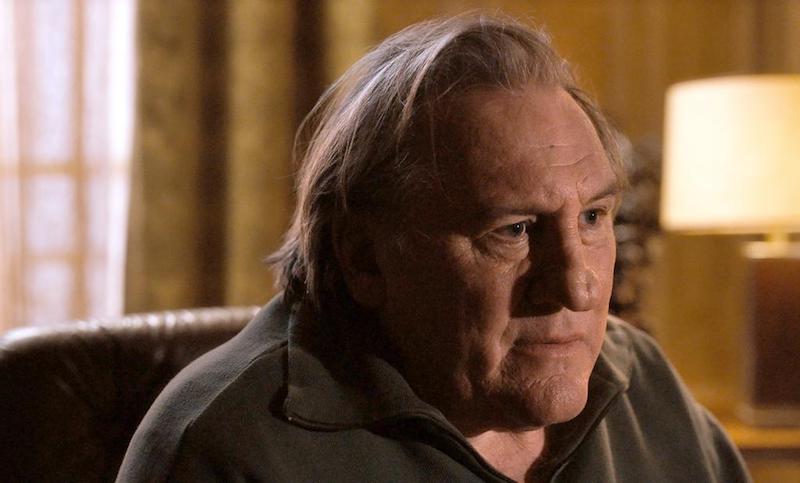

The film ends with Depardieu’s clairvoyant (pictured below) Have you ever looked for those kinds of answers?

I've been to a psychic, in my twenties especially. I understand the thirst for it, wanting to know the truth. When you're hesitating about something or someone, you think it's going to help you. It does help in a way, if it defines what you're feeling already, but I find it dangerous, because anybody can tell you anything and then you go for it. It's all crazy, I think. Your belief system, that's what's most important. You need to trust your intuition.  Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set?

Did Depardieu apologise by the way, for his criticism of you? Any humble pie on the set?

No. But I didn't need an apology. Actually three months after his declaration I saw him by accident in the street. I went to him and I took him in my arms and I said ‘Gerard why are you so mean to me? What have I done to you?’ And he said 'No, no, no, I'm saying stupid things, don't believe them.’

He then said, ‘I'm fed up that you're working with perverse directors’. I asked him who he was talking about. And he said, ‘Well, Leos Carax and Haneke’. But then he said that [Haneke's] The White Ribbon is actually a good film. After we separated I thought, ‘Well he's made films with Pialat, he's made films with Blier! I think he was just caught out by meeting me like that.

You know, the first time I ever went on a film set it was Danton [which starred Depardieu, in 1983]. I was just 18, still in high school. A friend of my father's was working on the film and invited me to watch the shooting. I was excited. And Gerard came to me, very open, and he said ‘What are you doing here?’ I said I was to be an actress. He said, ‘Work on your classics’. He was very cute and generous. So when suddenly years later his declaration happened, I was shocked.

So many of the scenes in the film feel raw, immediate. Did you try different ways of playing them?

No, because we didn't have a lot of time. We shot the film in five weeks. Very quick. Even the Depardieu scene is one day. So I had to make sure that I knew my text. Then you just throw yourself into the scene.

How did you find the experience of working with Claire Denis?

It was beautiful. It was like watching a painter. It was not always the logical way, she would go one frame, one shot at a time, working in steps, more than having the general idea of it and knowing exactly which shot she wanted. It was moment to moment, which I liked. I was learning by seeing her see.

Also she has such respect for human beings. She loved all the characters. There was no hierarchy, it was a very moving way of going through a film.

And you’re working with her again?

Yeah, in one year we've made two films together. That’s never happened to me. Science fiction. Nine actors in this space, coming from very different places. It was exciting.

Is there a different spirit on set when working with a female director?

I've never really felt that, because you work with the sensibility and the intelligence of someone. The complicity is not sexual. There's a seduction that's happening between the actors and director, but the seduction has to do with the fact that we need to create this fire between us, so that we can go into the work together, see if we need another take, never losing time. You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?

You’ve been working now for some 30 years. How do you stay challenged or engaged?

I’m always trying to find something new, that I’ve never done before. Repetition feels like near death. Creation is about the new. Something is going to happen but you don't know what. So you're moving towards that moment.

Life gives me things, I say yes or no. Or I create encounters. Abbas Kiarostami [Certified Copy, pictured above] and Bruno Dumont [Camille Claudel 1915, Slack Bay] were directors I was dreaming about working with – so you have to pick up the phone or go to that person and say it. Sometimes it's that’s simple.

So what was the challenge in this film?

I think it was the writing, because it was already there, I just had to put my hand in the glove. That was a new kind of situation for me. Most of the time we are really trying hard as actors because the writing, the script is not precise. But with Christine it's been felt, it's been lived.

When a script is not well written it's usually because it comes out of the head and not out of experience, and you really feel it when you’re acting and learning the lines. But on this one I felt lifted by the writing, and by the actors.

You’ve done nudity before, but not often, and this film goes straight into a long nude scene. Are you ever comfortable with such scenes?

You kidding me, I'm fucking scared! But I'm doing it. I think you've got to go into your fear, that's the challenge of it. So you can learn something from it, and change the fear eventually. Singing is very frightening to me, because I’m not a singer, and I’ve discovered how to put emotion into the singing. And the same with dance. But I'm frightened like anybody.

- Let the Sunshine In is released in cinemas on 20 April

Overleaf: watch the trailer to Let the Sunshine In

The second thing I noticed about Miloš Forman, who has died at the age of 86, was the spectacular imperfection of his English. All those decades in America could not muffle his foghorn of a Bohemian accent, nor assimilate the refugees from Czech syntax.

Clio Barnard has quietly been building a reputation as one of Britain’s most human storytellers. Her debut feature The Arbor was a mesmerising look at the life of playwright Andrea Dunbar, blurring the line between documentary and performance.

Daniel Day-Lewis doesn’t look like a 60-year-old retiree. He’s wearing a striped T-shirt under a dark blue shirt, light brown trousers which descend no further than mid-calf and boots laced high above the ankle he could easily have worn as a young actor in My Beautiful Laundrette. Ditto the earring. He remains as thin and sleek as a whippet. Only the silvery stubble of his hair betrays the march of time.

In 2016 the Bristol Old Vic turned 250. To blow out the candles, England’s oldest continually running theatre summoned home one of its most splendid alumni.

Gareth Tunley, director of the psychological drama The Ghoul, and Alice Lowe, one of its stars, are a duo with eclectic tastes. They share a background in comedy, but cite everything from punk to surrealism and the occult as influences on Tunley’s directorial debut, which was produced by Ben Wheatley.

Olivia Williams’s first film was, (in)famously, seen by almost no one. The Postman, Kevin Costner’s expensive futuristic misfire, may have summoned her from the depths of chronic unemployment, but the first time anyone actually clapped eyes on her was in Wes Anderson’s Rushmore, in which Bill Murray most understandably falls in love with her peachy reserved English rose. Then came The Sixth Sense, in which with great subtlety she in effect gave two performances as the wife/widow of Bruce Willis, depending on whether you were watching for the first or second time.

The summons to Hollywood was quite an introduction for someone whose entire twenties had been missed by all but fans of poetic dramas dutifully exhumed by the RSC. Her career since then has been a shining example of the old adage that a well-planned acting career is a marathon not a sprint. When Williams, armed with a degree in English from Cambridge, started attending auditions various famous contemporaries were always ahead of her in the queue. Some now work a great deal less than she does. Her CV includes her readings of great icons – Jane Austen in Miss Austen Regrets, Eleanor Roosevelt in Hyde Park on the Hudson. She was the tragically betrayed sister in The Heart of Me (source: Rosamond Lehman) and, by complete contrast, the finally triumphant wife of a PM in The Ghost (source: Robert Harris). There was a tragic echo of her nursery teacher from Rushmore in the secondary school teacher she played in An Education who is eager for her pupil not to throw off her future for love. She has also joined the trail of British actors starring in major US TV series in Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse and Manhattan, which told the story of the Manhattan Project. She was back on the BBC in The Halcyon, as the chatelaine of a smart hotel in wartime.

In all this screen work, Williams has been an occasional visitor to the stage. Whenever she does go back, as often as not it’s to the National: the Princess of France in Love’s Labour’s Lost, Amy O’Connell, who dies after an abortion in Harley Granville Barker’s Waste, and now in Lucy Kirkwood’s Mosquitoes. In Kirkwood’s first play since the award-winning Chimerica, Williams plays a high-achieving physicist domiciled in Switzerland, lured thither by the Large Hadron Collider at Cern. Her sister Emily, played by Olivia Colman, a low-achiever stuck in Luton. Hark what discord follows (pictured below: the two Olivias in rehearsal). Olivia Williams talks to theartsdesk.

OLIVIA WILLIAMS: No because as an actor you’re constantly pretending you can do things that you can’t, be it speak a foreign language, dance, ride a horse, juggle. You find ways of looking like or sounding like or dressing as if you do know what you’re talking about, and you try and learn the lines well enough that it falls out of your body as it would out of somebody who does know what they’re talking about. Problems arise if anything goes in any way off piste. At the moment I’m struggling with logarithm and algorithm which I am sure are two very different things, and I swear I heard a physicist snort with derision when I stumbled over the line last night – and then you fall into a black hole, which is a relevant analogy in this play, and you can’t get out again. But it’s no more frightening than if you’re trying to pretend you can juggle and you drop a ball or when the horse turns left when you thought you were telling it to turn right – neck reining in the US works on the opposite principle to UK reins, which makes for disaster when acting on a horse on a precipice.

On Manhattan they found us physicists to talk to and they sort of rolled their eyes in an “I thought as much” way. Because actors don’t ask them about particle physics; we ask them what model of Birkenstock they wear to work or what they had for breakfast or whether they have time to brush their hair in the morning. You ask all the wrong questions for a physicist but the right questions when you’re trying to impersonate a physicist.

When reading the play it was fairly clear to me that you would be playing Alice not Jenny.

I’m very very offended by that. Nonetheless you are correct.

Is there a part of you that would love to be cast as the calamitous dimwit? When I did The Heart of Me I clearly stated in the audition that I wanted to be up for the Helena Bonham Carter ditzy arty sister with loose morals and a free spirit, not the uptight needed-a-good-shag-against-a-firm-surface sister. And recently when I was in Waste there were two roles I could have played – the earnest, possibly lesbian, bluestocking sister and the tragic party girl. I asked if I might be considered for tragic party girl. I owe it to the broadmindedness of Roger Michell that he agreed to cast me as Amy O’Connell. So on one occasion that has come to pass. Not one disapproving or over-educated phrase escaped her lips (pictured above: Williams with Charles Edwards in Waste, photo by Johan Persson).

When I did The Heart of Me I clearly stated in the audition that I wanted to be up for the Helena Bonham Carter ditzy arty sister with loose morals and a free spirit, not the uptight needed-a-good-shag-against-a-firm-surface sister. And recently when I was in Waste there were two roles I could have played – the earnest, possibly lesbian, bluestocking sister and the tragic party girl. I asked if I might be considered for tragic party girl. I owe it to the broadmindedness of Roger Michell that he agreed to cast me as Amy O’Connell. So on one occasion that has come to pass. Not one disapproving or over-educated phrase escaped her lips (pictured above: Williams with Charles Edwards in Waste, photo by Johan Persson).

In Mosquitoes you’re playing a scientist from a family of scientists and Jenny is the odd one out. That is somewhat analogous to your own position as the only non-barrister in a family of barristers. Do you ever wonder what would have happened if you’d gone into law or has the decision to veer away from the family trade felt right all the way through?

No, I’m constantly yearning for the barrister’s life. I consider it a stupid mistake on a regular basis. But the thing that convinces me that it wouldn’t have gone so well is I do have a zero capacity to read things I don’t want to read and lawyers do have to do a lot of homework. The only reason I learn lines is because I love acting. And if I don’t love something I really can’t do it. I’m just incredibly lucky that I manage to earn money doing something I love. It’s a terrible example to my children. I am constantly telling them to do things they don’t want to do when I know I never did and I never could. I think my greatest regret is I’m never cast as a lawyer. Never been a lawyer. I’ve actually been in an audition and given them my best lawyer and they go, “No, no, lawyers don’t do that.” And I’m like, “No they do, that’s exactly what they do!”. But I look forward to impersonating my parents one day. Maybe I’ll make it onto the Bench instead. Time for a TV series about judges.

Why do you love acting?

I’m just about as happy as I can be between action and cut and between curtain up and curtain down. I remember coming back from my first day of acting in The Sixth Sense. I’d been hanging around in Philadelphia for weeks and then I got to do a scene. I came off the set and the driver said, “Are you on drugs or something? You’ve got a dumb smile on your face.” And I said, “No, I’ve just spent the day acting. I couldn’t be happier.”

Although you didn’t go into law, you do have a very good degree from a very good place. Has it been useful to you, that immersion in English literature?

For the record it was a pretty average degree from a very good place. but that’s a good question. On immediately leaving that university and going to drama school I think I was given a hard time about it and I was resentful of that. “You come here with your Oxbridge ways” was the underlying tone. But the truth is that I did go there with my Oxbridge ways, and when I started acting professionally and watching other actors act I finally realised that a critical approach to the text is a massive handicap - you shouldn’t be finding fault with the text, or tracing its roots in the Indo-European tradition, you’re trying to be it. I learned so much from [the actress] Anastasia Hille – more about acting than anybody else. Her approach to the words was entirely emotional, and that needs to be your response. You need to stop judging it and incorporate it in the literal sense of the word – turn the text into a part of your body. Embody it.

But I have found as I got older that a facility with language, an understanding of how it’s constructed and connecting what I learned with what I’ve observed, feeds my pleasure in what I do. Lucy Kirkwood breaks down language and punctuation in a completely courageous way – it’s almost like doing a verbatim play where actors have to learn exact pauses and intakes of breath. But what you find with Mosquitoes is that it looks like it’s verbatim and all very naturalistic, then you realise it’s incredibly musical. It’s like jazz. I say that cautiously because there was a programme on Radio 4, which is the fount of most things interesting and truthful, about how the phrase “it’s like jazz” is overused and misused. But there is incredible syncopation and layering of different rhythms in Lucy's language. When you see it on the page it’s terrifying. I have a wonderful accent and voice coach called Jill McCullough and she has a learning technique where you click your fingers for a comma and clap your hands for a full stop. And that has made learning Mosquitoes – and I say this advisedly – like jazz. When were you last asked about The Postman?

When were you last asked about The Postman?

There was a nasty rash of conversations that came up over coffee in the rehearsal room. I was being asked by the young ones about my professional snog list which I still maintain is pretty impressive even though it only is appreciated by someone of our generation. To younger actors it’s just this list of old men that their grannies fancied. That was the last time I was asked about The Postman.

That phase when you were in three big films with Kevin Costner, Bill Murray and Bruce Willis was quite an introduction to the film industry. How do you now think of that phase of your career?

I had a great time and I can’t really believe it happened in some ways. It was like being kidnapped by aliens. I guess if you look at some of my contemporaries, I’m not there any more, I’m not in Hollywood, not living there and not fighting the fight. And yet rehearsing this play here and now I really can’t think of anywhere I’d rather be. I do genuinely believe that if that hadn’t happened to me I wouldn’t be doing this work now. I got incredible access and insight to amazing things (Carrie Fisher's Oscar party) and amazing places (dropped from a helicopter onto a snowy peak at Jackson Hole). I went from complete ignorance to working with some of the foremost people in their field and I would have been an idiot not to learn from that - to appreciate that.

The Sixth Sense was shot by Tak Fujimoto who shot Rosemary’s Baby. I made a film with Roman Polanski, seeing what lens he uses, where he puts the camera, how he constructs a scene. I’ve made a film with Wes Anderson. And just to be in the orbit of Bill Murray – he is an extraordinary man and an extraordinary actor and an extraordinary mind. I’ve worked with him twice in two inconceivably different films. I took Bill Murray to see Richard Briers in Ionesco’s absurdist play The Chairs on Broadway. Bill knelt at Richard’s feet in awe. It’s making me smile now, to remember it. And I learned about acting on film. Kevin was directing and acting in The Postman so he would haul me over to the monitor and show me my work and show me how to make it better. Absolute masterclass. Whatever you say about Kevin – you might not say anything about Kevin, never mind have an opinion on his oeuvre – but he knows how to work it on film. He knows what he’s doing.

You have done two big television shows in the States, Dollhouse and Manhattan, both of which were cancelled. Was two seasons enough for you in both cases?

You have done two big television shows in the States, Dollhouse and Manhattan, both of which were cancelled. Was two seasons enough for you in both cases?

Whenever I do a job I do it to be best of my ability. I might fight like a dog during negotiations not to go away from my family for four months of the year, and certainly I fight being trapped in feudal contracts that were made illegal in England around the time of Magna Carta. But once again I have been very lucky. I adored Dollhouse (pictured above) and was directed by Joss Whedon who wrote all my dialogue and I joined his crazy Whedonesque world – I had absolutely no idea of its existence, but a working knowledge of Comic Con and sci-fi is probably more relevant to an actor now than reading The Empty Space.

I loved Manhattan. I fought going to live in Santa Fe, but ended up galloping around the high desert with some fearless cowboys and I learned things about the atomic weapon that are very useful to an Eighties member of CND. I would not have missed it for the world and it was heartbreaking when it was cancelled. We needed another season of Manhattan. We shot the Trinity test but never made it to the dropping of the bomb, and I think it is a matter of some urgency that we remind ourselves of the consequences of atomic warfare. The fallout from the Trinity test is still killing people in New Mexico.

When you first start acting, a young woman’s drama is traditionally centred around finding a husband, and ends with her marriage. I suppose it is progress that in the middle period of my career, the drama followed me into marriage but seemed to centre on the fact that every single one of my husbands died – The Postman, Rushmore, [spoiler alert] Sixth Sense. I had to warn any man cast as my husband, “You’re not going to make it to the final credits.” I am grateful that great parts are being written for middle-aged women, but as you rightly point out, the drama now seems to centre on the fact that aged around 49, my character’s husband – if she has managed to find one and he’s not dead – is going to fuck somebody else.

- Mosquitoes is at the National Theatre until 28 September

Overleaf: Olivia Williams's filmography in pictures