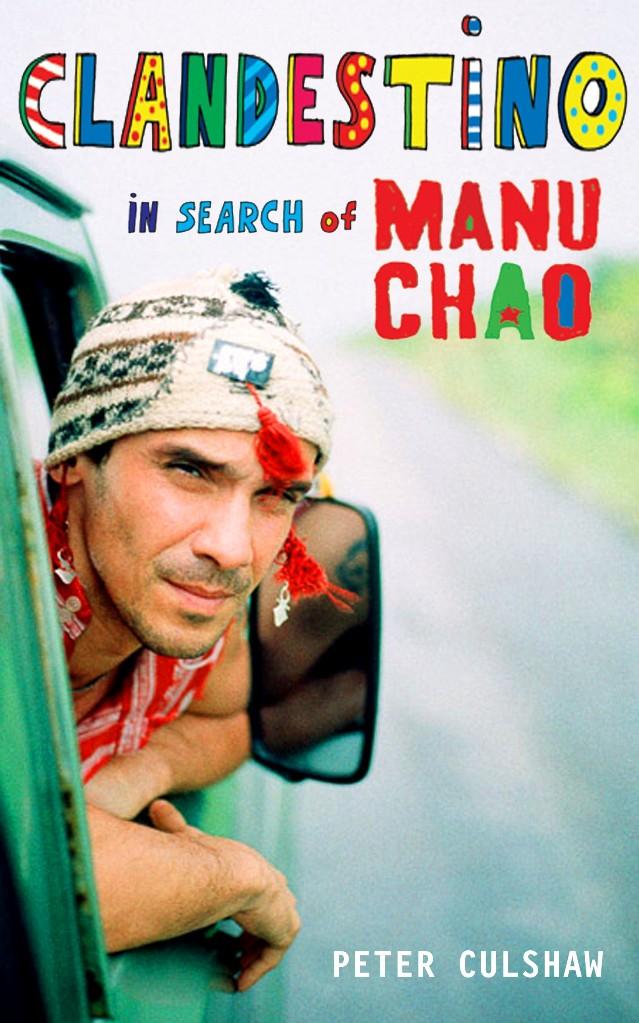

Manu Chao isn’t exactly a household name in the UK. In much of Latin America and Europe, however, he’s an iconic figure who is probably the closest thing to Bob Marley there is, a symbol of hope for the dispossessed. He’s a somewhat elusive figure, a wandering artist who for years never had his own place, a mobile phone or a watch, forever on the move, addicted to travel. In the title song of his 1998 multi-million selling classic Clandestino he sings of how “to run is my destiny... lost in the grand Babylon.” The song is not just autobiographical, but is also about the hypocrisy of Western countries who try to ban immigrant workers while at the same time benefitting from their illegal status by paying them pitifully low wages.

Clandestino seemed to look both backwards to a time when songs meant something, when people thought music could change the world, and forwards to a new globalised pop. At the cross-fade of the millennium, it sounded perfect – a radical pop masterpiece that united, irresistibly, a European and South American perspective. Chao was born in Paris to Spanish parents, hearing boleros at home and rock'n'roll in the streets.

If I’d been more up to speed on French rock music, I would have been less astounded by Clandestino. Manu Chao’s previous outfit, Mano Negra, had been the biggest band in the history of French rock, with legions of followers in Europe and in South America, where they still have a mythic status. When asked the meaning of anarchy on Argentine TV, they trashed the studio, and woke up famous.

Plenty of people agree with their manager Bernard Batzen when he claims that had the band actually promoted their albums properly, instead of going off on quixotic missions like a four month boat trip around Latin America, or a rail trip through the guerrilla chaos of Columbia in 1992, described at the time as “less like a rock’n’roll tour, more like Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow," they would have been as big as U2 or Coldplay.

I didn’t know I was making a record. It was pure therapy

But Mano Negra broke up, bitterly, before their best-selling album Casa Babylon was even released (See video above). For three years, between 1992 and 1995, Chao was plunged into an often suicidal depression. He went missing-in-action, a nomad who often thought of suicide, playing the bars of Rio and Tijuana, experimenting with peyote in Mexico City, entertaining children of insurgents in the Chiapas (he sampled the charismatic activist Subcommandante Marcos on Clandestino), slowly returning to relative sanity after a motorbike ride from Paris to the greenness of Galicia with his father, the writer Ramon Chao. But if he was a depressive, he was a manic one, and while he was unable to stay in one place he was continually writing songs. As he says, “Clandestino was the result of that time – I didn’t know I was making a record. It was pure therapy.”

Manu felt it was likely to be his last record, and most music professionals thought it would have little commercial success. The trajectory of the album was most unusual – it was only a year after its release that it got into the French top ten. Rather than slipping away, it never left the charts for the next four years.

Virgin’s modest and low-key marketing of the album, with its anti-consumerist aura, turned out to be perfect; people discovered the album for themselves. It initially became the soundtrack of choice for backpackers in hip beach destinations like Koh Samui in Thailand and Puerto Escondido in Mexico – its bitter-sweet quality perfect for the moment the sun goes down, echoing the transitoritory nature of life. The record is full of a Manu neologism: malegria – happy sadness. Eventually it was huge hit, especially in mainland Europe and South America, selling over five million copies (and probably the same again if you count the pirated ones).

Once it became clear that it was a success after all, Virgin committed to the follow up Proxima Estacion-Esperanza, and Manu assembled a crack band. Almost immediately they played to a crowd of over 100,000 in Mexico City. One thing he did do, as he had promised himself he would do if he ever got a chance to “use the microphone” again, was use his fame to promote causes he believed in. In stops across South America, he publicised fights against water privatisation in Bolivia, or supported community radio stations in Argentina, or became one of the best known opponents of globalisation at the 2001 G8 meeting in Genoa, even though he says “There’s nothing so corrupt as to be a leader.” Many leaders have, however, tried to co-opt him – he was on the way to meet Hugo Chavez when he asked that the car turn back. He is suspicious of the Bonos and Bob Geldofs who hobnob with Presidents (and, anyway, he doesn’t really believe that politicians have much real power any more). The current dialectic is between neighbourhood action and power of the mafias – be they drug, bank or corporate mafias.

When it came to writing my book on Manu, it was the chance to publicise some of his political causes that that appealed to him more than a conventional rock star biography. In fact, the book ended up as two books in one – the first his back story, through the fascinating alternative 1980s in Paris (where he was managed by a porn star called Marc Winandy with “the biggest dick in the business”), followed by explosive success, those insane boat and train tours and his breakdown and lost years.

The second half of the book is an on-the-road gonzo portrait of Manu when I was summoned, often at a moment’s notice, to Buenos Aires at a psychiatric asylum (pictured right) where Manu recorded with some inmates, to Mexico, where gigs were cancelled due to drug gang outrages, to Madrid with prostitute activists. (One of his best songs, “Me Llaman Calle”, [see video below] is about working girls whose bodies are for sale but whose hearts aren't. When it won song of the year he got a bunch of them to accept the award. Cue massive publicity.) Then there was the time I went with him to the Algeria Sahara for a film festival at a Polisario refugee camp in Tinduf (where, surreally, I ended up playing bongos with Javier Bardem).

The second half of the book is an on-the-road gonzo portrait of Manu when I was summoned, often at a moment’s notice, to Buenos Aires at a psychiatric asylum (pictured right) where Manu recorded with some inmates, to Mexico, where gigs were cancelled due to drug gang outrages, to Madrid with prostitute activists. (One of his best songs, “Me Llaman Calle”, [see video below] is about working girls whose bodies are for sale but whose hearts aren't. When it won song of the year he got a bunch of them to accept the award. Cue massive publicity.) Then there was the time I went with him to the Algeria Sahara for a film festival at a Polisario refugee camp in Tinduf (where, surreally, I ended up playing bongos with Javier Bardem).

While Manu hasn’t released a big album for seven years, he has put out recordings on the internet and has numerous albums – including the splendidly titled The Worst Of the Rumba Volume One - which he could release if was inclined. Numerous remixes emerge all the time. But in the current music business, where all that is solid melts into air, it’s tricky to know the best thing to do with your music. He’d probably be happy to put it all out for free – his management and record company are, understandably, less sanguine about that approach.

Someone called him a “post-European trickster”, another, absurdly perhaps,“the last free man”

On this weekend's Loose Ends on Radio 4 it was implied that I was an obsessive. “Who are you going to stalk next?” was the question. The obsession was probably more with trying to figure out Manu’s contradictions: a shy guy who plays stadiums, an anti-globalisation activist who is a global star, a millionaire back-packer. Someone, too, who is at least trying to keep some integrity. When offered a million dollars for a bank ad, he turned it down, while his ex-heroes Iggy Pop and Johnny Rotten take the ad money. He refuses sponsorship for gigs. Someone called him a “post-European trickster”; another, absurdly perhaps,“the last free man”. He is, in spite of all the contradictions, a positive force in the world.

- Next weekend theartsdesk will be running an extract from one of Peter Culshaw's on-the-road adventures with Manu Chao.

- Peter Culshaw’s book Clandestino: In Search of Manu Chao (Serpents Tail) is published on 9 May. Available through Amazon or good booksellers

Follow Peter Culshaw on Twitter

Watch the video of Manu Chao's classic song "Clandestino"

Add comment