The conundrum central to library music is that it was not meant to be listened to in any normal way. Yet, in time, this is what happened. What ended up on the albums pressed by companies like Bruton, Chappell, De Wolfe and others was heard by subscribers – the records did not end up for sale in shops or on the record players sitting in the nation’s homes.

Those receiving this music were from the advertising, film and television industries. They were looking for material which could feature in their productions without the need to book a recording studio and employ an arranger, composer, musicians or producer. It was an efficient and economical way to source themes and incidental music. Pay your subscription, take delivery of the albums, hear a track fitting the bill and make the deal to use it to accompany the visuals. Until these albums appeared in second-hand shops, few record buyers realised this world existed.

Awareness of the library music phenomenon increased during the mid-1990s, hand-in-hand with the easy listening trend. Digging into musical esoterica was at a previously unachieved height. At first it was the groovy, swinging material which ended up on compilation albums. Composer/players like Alan Hawkshaw, Keith Mansfield and Alan Parker became familiar names. Library albums were going for large sums. Weirder recordings were swiftly discovered: curios from the Bosworth Music Archive; material by oddball experimental/jazz composer Basil Kirchin. It was found that Jimmy Page and The Pretty Things had recorded for library organisations. There were French companies generating what is strictly known as “production music.” Italian ones too. This closeted, shadowy world generated a seemingly endless amount of music to be discovered. The real trick though, is to put shape on it. To find a narrative.

Awareness of the library music phenomenon increased during the mid-1990s, hand-in-hand with the easy listening trend. Digging into musical esoterica was at a previously unachieved height. At first it was the groovy, swinging material which ended up on compilation albums. Composer/players like Alan Hawkshaw, Keith Mansfield and Alan Parker became familiar names. Library albums were going for large sums. Weirder recordings were swiftly discovered: curios from the Bosworth Music Archive; material by oddball experimental/jazz composer Basil Kirchin. It was found that Jimmy Page and The Pretty Things had recorded for library organisations. There were French companies generating what is strictly known as “production music.” Italian ones too. This closeted, shadowy world generated a seemingly endless amount of music to be discovered. The real trick though, is to put shape on it. To find a narrative.

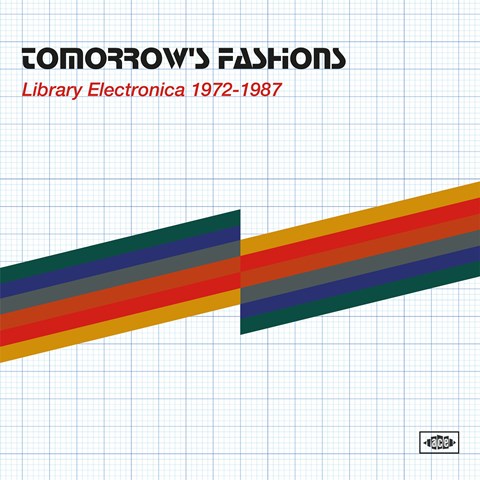

Which is where Tomorrow's Fashions - Library Electronica 1972-1987 steps in. Compiled and annotated by author and Saint Etienne member Bob Stanley, it looks at exactly what its title says. He opens his introductory essay thus: “Nothing said new or modern or futuristic quite like a synthesiser in the 70s and 80s. If you were shooting an advert and you wanted your product or your company to appear forward-thinking and ahead of the game, then you would want something electronic, something out of the ordinary. When TV producers and advertising directors started searching for music that sounded like 'Tubular Bells' – and then Tomita, and later Jean-Michel Jarre – music libraries such De Wolfe, Bruton, Parry and Chappell had to have the tracks readily available.”

The compilation's 24 entrants include tracks credited to the suitably mechanoid Tektron and Unit 9. There is also the more prosaic Soul City Orchestra. Best of all are the fantastically handled Wozo and Rubba. Behind these lay names such as Simon Park (Soul City Orchestra), and John Saunders and Monica Beales (Wozo: Saunders also traded as Astral Sounds). Rubba were Karl Jenkins and Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine. Tektron was Trevor Barstow. The original albums with this music had sleeves featuring illustrations of, yes, synthesisers. And a bird in flight over a forest, cloud formations, crashing waves or twigs – pretty new agey. Some Tron-sque imagery too. One cover, Bruton’s Tomorrow's World album (1982, pictured left), shows human interaction with a computer screen this-far from the core concept of the David Cronenberg film Videodrome, released the next year. The period covered by Tomorrow's Fashions edges into when digital music technology arrived. Sampling is generally absent. Mostly, this is an analogue world.

The compilation's 24 entrants include tracks credited to the suitably mechanoid Tektron and Unit 9. There is also the more prosaic Soul City Orchestra. Best of all are the fantastically handled Wozo and Rubba. Behind these lay names such as Simon Park (Soul City Orchestra), and John Saunders and Monica Beales (Wozo: Saunders also traded as Astral Sounds). Rubba were Karl Jenkins and Mike Ratledge of Soft Machine. Tektron was Trevor Barstow. The original albums with this music had sleeves featuring illustrations of, yes, synthesisers. And a bird in flight over a forest, cloud formations, crashing waves or twigs – pretty new agey. Some Tron-sque imagery too. One cover, Bruton’s Tomorrow's World album (1982, pictured left), shows human interaction with a computer screen this-far from the core concept of the David Cronenberg film Videodrome, released the next year. The period covered by Tomorrow's Fashions edges into when digital music technology arrived. Sampling is generally absent. Mostly, this is an analogue world.

Tomorrow's Fashions is sequenced with care so it’s a linear, satisfying listen. It is not a pot-luck grab bag. The opening track is Simon Park’s “Coaster” (1982). With human drums, it glistens, is gently funky and exhibits a mind-set close-to the roughly contemporaneous Human League instrumental “Gordon’s Gin.” The earliest track is Sam Spence’s “Leaving” (1972). It pre-figures what Jean-Michel Jarre would be up to; considering this, it’s spooky that Spence had studied at the École Normales de Musique de Paris. “Leaving,” with its bargain-basement Tangerine Dream vibe, also ended up as a German single in 1973. Any such external musical connections with this material are, of course, imputed, implied, but a prime goal of library music was to tap into and co-opt current stylistic zeitgeists. This is how it would get to be used. Take Rubba’s fantastic “Space Walk” (1979), which is along the lines of both Jean-Michel Jarre and Space (the French synth-disco combo, not the Liverpool band).

While the endlessly fascinating Tomorrow's Fashions - Library Electronica 1972-1987 deftly opens the door on what's been a less familiar aspect of library music which aesthetically ripples through recent-ish labels like Ghost Box and Warp it also, perhaps more importantly, confirms that while these composers and musicians operated out of the public eye without any recognition, they did draw from the wider world. The music itself proves this, that these often shadowy figures and their creations were no further from the latest flavours in popular music than what was on sale at the high street’s hippest record shops. How extraordinary it is, then, that what’s heard here has taken four or five decades to reach today’s retail outlets.

- Next week: Sex Pistols – Looking For A Kiss In Kristinehamn. Ripping document of Rotten and Co's 1977 tour of Sweden

- More reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Add comment