As there's something of a forest theme this weekend on theartsdesk, with the Royal Opera House's If-A-Tree festival curated by Joanna McGregor with Scanner, and a report from this year's Borneo Rainforest World Music Festival, and here, a diary of an extraordinary trip I took in 2003 to sample the culture and music of the Pygmies deep in the heart of the Central African Republic.

Day 1: The Beauty Contest

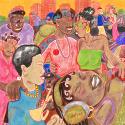

The Miss Bangui beauty contest takes place at the Palais de l'Assemblée, an edifice built by North Koreans, where the Central African Republic's parliament used to meet. Since democracy was suspended following a recent coup, they have found other, more entertaining uses for the building. There are soldiers with Kalashnikovs on either side of the stage and girls strutting their stuff in traditional African wear as well as formal and casual Western clothes. Number 10 has won the title but Regis Sissoko and I suspect a fix because for elegance, style and sheer beauty, we agree that No 16 should have claimed the prize of a trip to Paris.

To be honest, lovely as the girls are, I'm more concerned with bonding with Sissoko, the fixer and music promoter who will take me deep into the forest to meet the Aka pygmies. In a place like this you need a Sissoko figure who knows where it's safe and where it's dangerous and who needs bribing and how much.

We had flown to the capital of the Central African Republic via Paris and Chad. The Air France aeroplane couldn't land because of fog and circled the airport for an hour. The Jehovah's Witness missionary next to me on the flight said Bangui airport has no radar and started to pray.

When we land, my glasses immediately steam up in the heat and impossible humidity (Bangui, pictured left). There are soldiers wearing cool blue sunglasses looking chic as well as deeply sinister, and there's mayhem in the terminal. Fortunately Sissoko - who, last we heard, was stranded by bad weather in Libreville, Gabon - guides us through the chaos and installs us in the Hotel Sofitel.

When we land, my glasses immediately steam up in the heat and impossible humidity (Bangui, pictured left). There are soldiers wearing cool blue sunglasses looking chic as well as deeply sinister, and there's mayhem in the terminal. Fortunately Sissoko - who, last we heard, was stranded by bad weather in Libreville, Gabon - guides us through the chaos and installs us in the Hotel Sofitel.

I feel like I've walked into Graham Greene's The Comedians. The place has seen better days, and its dubious guests include diamond dealers and soldiers you really wouldn't want to offend. Deals are whispered in the bar, while slinky hookers tout their trade. The man from the Foreign Office, while advising me not to travel there, had said that Bangui was "morally dangerous" - the Aids rate in Central Africa means that misbehaving with one of the girls would be like playing Russian roulette.

I first heard their extraordinary and haunting music in the Seventies on classic records by the musicologist Simha Arom. The Hungarian composer György Ligeti became obsessed by the complex polyrhythms and irregular multi-part vocalising of the pygmies, which became a great influence on his own work. Far from being primitive, the music of the pygmies is as advanced as anything in the Western canon. It may well be that only now are we actually catching up musically in the West with the complexities of this ancient music. All of which was a great excuse to visit them. I only wished they lived somewhere less volatile and violent.

Day 2: Brand Loyalty

Day 3: Nuns and Troops

Day 4: First Contact

There's a commotion at the mission. A large and deadly mamba snake has been discovered in Sissoko's room and his brother, who has been driving us, has killed it and cut off its head. Sissoko seems weirdly unfazed. "You could die slipping in your bathroom, after all. C'est le destin."

There's a commotion at the mission. A large and deadly mamba snake has been discovered in Sissoko's room and his brother, who has been driving us, has killed it and cut off its head. Sissoko seems weirdly unfazed. "You could die slipping in your bathroom, after all. C'est le destin."Day 5: River Serpents

The main way of punishing bad behaviour (the worst crimes seem to be stealing and incest) is to ignore the wrongdoer, a painful punishment in such a close community. At worst, a pygmy can be banished into the forest, where they find it impossible to survive alone. But mostly conflict is avoided, partly because, as a nomadic people, a group can split off and join another pygmy group. At certain times of year, larger groups of pygmies will gather; it's here that marriages are usually arranged.

The main way of punishing bad behaviour (the worst crimes seem to be stealing and incest) is to ignore the wrongdoer, a painful punishment in such a close community. At worst, a pygmy can be banished into the forest, where they find it impossible to survive alone. But mostly conflict is avoided, partly because, as a nomadic people, a group can split off and join another pygmy group. At certain times of year, larger groups of pygmies will gather; it's here that marriages are usually arranged.Day 6: Jungle Charms

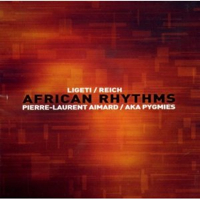

Pygmy culture is changing, although the fundamental structure seems strong. Superficial things change - when Arom visited these people 30 years ago, they all wore cloth fashioned from bark; now many wear T-shirts and jeans, some picked up during dates they played in Europe a few years ago. The tour was the brainchild of classical pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, who released an extraordinary disc (pictured left) that includes the music of the Aka pygmies and the piano music of Ligeti. Arom worried that appearing abroad might affect them adversely but it's noticeable that they take it in turns to wear these clothes and don't seem to have much of a sense of personal ownership.

Pygmy culture is changing, although the fundamental structure seems strong. Superficial things change - when Arom visited these people 30 years ago, they all wore cloth fashioned from bark; now many wear T-shirts and jeans, some picked up during dates they played in Europe a few years ago. The tour was the brainchild of classical pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, who released an extraordinary disc (pictured left) that includes the music of the Aka pygmies and the piano music of Ligeti. Arom worried that appearing abroad might affect them adversely but it's noticeable that they take it in turns to wear these clothes and don't seem to have much of a sense of personal ownership.Day 7: Forever Changes

Day 8: The Long Echo

- Find the Aka Pygmies music on Amazon

- The original article was printed in The Observer in September 2003

Add comment