theartsdesk Q&A: Abel Selaocoe | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Abel Selaocoe

theartsdesk Q&A: Abel Selaocoe

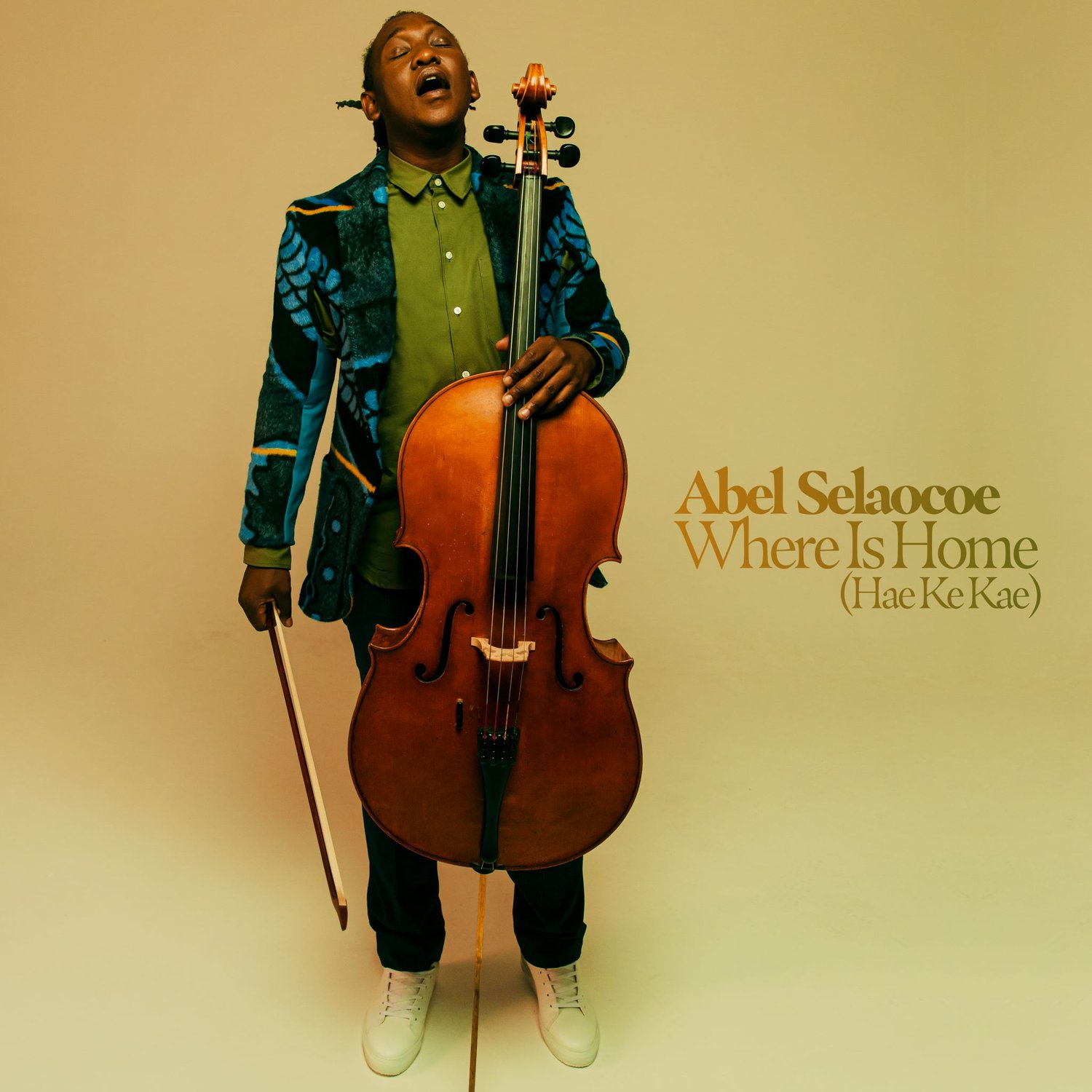

The South African cellist and rising star of World and Classical on the music, life and history embedded in his debut album 'Where Is Home'

South-African cellist Abel Selaocoe is about to begin his third major concert in London in under a year. As the support artist for kora player Ballake Sissoko and cellist Vincent Segal at the Roundhouse in January, he received a lengthy ovation for his 30 minute set, having demonstrated an uncanny ability to play the audience as dexterously as he plays his cello.

A few months later, he appeared with the Manchester Collective at the Southbank Centre, performing some of the pieces that make up his debut album on Warner Classics, Where is Home, alongside works by Stravinsky, Vivaldi and Elizabethan English composer Picforth. In January, his excellent three-part series Cello Retold was broadcast on Radio Three.

This weekend, he launches Where is Home at the Queen Elizabeth Hall with a 12-piece orchestra that comprises a string trio, kora player Kadialy Kouyate, his own Chasaba trio of Irish bassist Alan Keary and djembe player Sidiki Dembélé from the Ivory Coast, and Alice Zawadzki on vocals. To all this Selaocoe adds his own cello, voice, and body percussion, and a touch or two of audience participation, to make the concert experience truly a performance in the round.

Where is Home spans Sarabandes from Bach’s Cello Suites through a Platti Cello Sonata to Apartheid-era hymns in Zulu and a tribute to Tanzanian traditional musician Hukwe Zawose. Alongside them are self-penned pieces sung by Selaocoe in Sesotho, one of South Africa’s 11 languages, while a closing “Ancestral Affirmation” features the voices of his own family.

Selaocoe’s music unifies different sound worlds by identifying and drawing out the improvisatory spirits resident in both South African vernacular and sacred music and in the music of the European Baroque. Here he talks about identifying his musical homes, the moveable feast of combining the composed and the improvised, and his journey from Soweto Township to the Southbank Centre via the Royal Northern College of Music in his current home city of Manchester.

Tim Cumming: What does "home" mean to you?

Home comes in many forms, and that’s the idea of the album, that everyone should be exploring what that is and finding out, on that journey, what it means to them. It’s finding the spaces that empower you, and nurture you. It’s not always a geographical space. It could also be the things you do to keep yourself alive and healing. It’s about looking for those things that are nurturing and that also challenge you to feel that you’re progressing as a human being.

What are the musical traditions that you would call home?

I’m a contemporary of my influences. I grew up learning classical music from such a young age; from nine I was already playing the cello, learning the fundamentals. Bach, Baroque music. That was the ground foundation we learnt music upon. At the same time, our home was full of African culture. There was always singing. Hymnal music was one of the biggest things. Spiritual ancestral music was also a huge thing.

By saying I’m a contemporary of these things, I have to allow them to live in one space, otherwise I feel I’m always switching, but the older I become the more attuned I come to the idea that these things have formed a DNA of their own, that they belong in the same space together.

Moving in the album through different sonic spaces, is quite natural, and I have to find ways Baroque music can speak to African music, thinking about four-part harmony, about the people who came with the language of Haydn, of Bach and those hymnal chorals, and my father singing the same bass lines, but in our language. Finding the fabric that binds those things together is very important to me, so I’m always looking for ways. I’m crazy about African violins, and transporting their language to the cello, and also transporting the voice to the cello.

There’s a lot of voice work on the album, as well as cello – how have those two disciplines evolved and do they influence each other?

It’s part of the same process. Most of the ideas that came in terms of the compositions came from the voice at first, and then translating that to the cello was a simple process. The soul holds the voice first before it’s attached to anything else. You sing a melody before it comes, a rhythm before it comes, then you translate it to the rest of the world.

I’m a product of my influences or of what I am around. Some of the cultural spaces I have come into use a type of expression of the voice where it’s not throat singing, but more a collective voice that is extremely low. The kids who go to initiation school, who finally become men, all sing in this low voice, and that has always stayed with me. From that influence I started searching for something that was connected to this low kind of singing. There are women who throat-sing on the eastern Cape, and overtone sing, especially for boys going to initiation school. So with those influences, where do I put that into my space, and I think the cello and its range works perfectly with it. It can be a communal voice, between the cello and the throat-singing.

When did you first start on the cello?

It started with family. My brother was a key inspirer. He was a bassoon player, learning at a school in Soweto. And that’s played a huge role in shaping what I am and what I ended up being to this day. I went everywhere with my brother, and he took me to the music school. He already knew about self-expression within music, and he thought, ‘we need something that can give you the range to sing whatever you want’. So he gave me the gift of choosing the cello. From then on, we knew we could express anything through our instruments.

You studied at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester?

The RNCM was a place for experimentation, a place to fail a lot, to make a lot of mistakes, and to learn classical music at its core. Shostakovitch, Bach, you name it, at an extremely high level. The professor was extremely open-minded. She said, ‘bring your culture here, bring yourself here. We’re saturated with cellists who are all doing the same thing’. So to be allowed to do this in an institution like the RNCM was a gift that I’m not sure I would have gotten anywhere else.

Is there the same distinction between vernacular and formal music in African music, as there is in European?

Yes absolutely. The cello does not come from that world and it requires the person who is taking this instrument through this world to be a curious being, to be asking questions, all the time. Spending time with the amazing percussionist Sidiki Dembele has been a godsend, because he would speak the rhythms and then I would have to find my own way of putting those rhythms onto the cello. The griot culture they’ve learnt is not a part of my system, and for the cello to be at home in those places, the only way to be and the only demeanour to assume, is curiosity.

How is composition and improvisation combined on the album?

Improvisation permeates the whole thing, for instance when we play the Platti sonata. Baroque takes the same form as jazz – you have a chart, you have really minimal information of what to do, of the melody and the chords, and we play with an incredible oboe player, who will take this and really make it who she is. So this is a land of improvisation, and understanding the culture you are coming from.

At the same time, the ability to create a unique voice is up to you, not to what’s written. So that, mixed with kora playing, where both kora and cello were played in their own royal courts, and probably at the same period, have this structure, while at the same time they have this land of improvisation.

The cello and the kora have to have a dialogue, because they’re almost cut from the same cloth, but from different sides of the world. When you think about how it is made, the strings are similar, the body is extremely similar, the size for creating resonance for both instruments is very similar, and the culture is parallel and speaks to each other in a lot of ways. We’d improve between the movements, and the kora also played some of the continuo arrangements – the accompaniments for the sonata. So the worlds are mixing but we have to be true to the composer and to ourselves, and understand when to do it and when not to do it.

Is your album a long-prepared statement, or more an in the moment expression of where you are now?

It’s about where I’ve been, where I am now and where I want to go. Some of the music, like “Ancestral Affirmations”, which is full of prayer and chant, takes me back to before I was born. I wanted that on the album, the idea of that kind of home existing, and finding a space for the cello in all this rhythmic music was very important. That’s been my journey for quite sometime.

And that’s my real home, that’s my father singing there, and my sister. Before we leave or when we arrive at home there has to be a hymn – there’s no arrival or leaving without a hymn.

- Abel Selaocoe’s Where is Home (Hae Ke Kae) is on Warner Classics

- He plays at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on Sunday

- More Q&As on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment