First Person: violinist and music director Bjarte Eike on bringing the Playhouse to his 'Alehouse Sessions' | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: violinist and music director Bjarte Eike on bringing the Playhouse to his 'Alehouse Sessions'

First Person: violinist and music director Bjarte Eike on bringing the Playhouse to his 'Alehouse Sessions'

Barokksolistene's freewheeling spirit of delight returns to the Southbank tomorrow

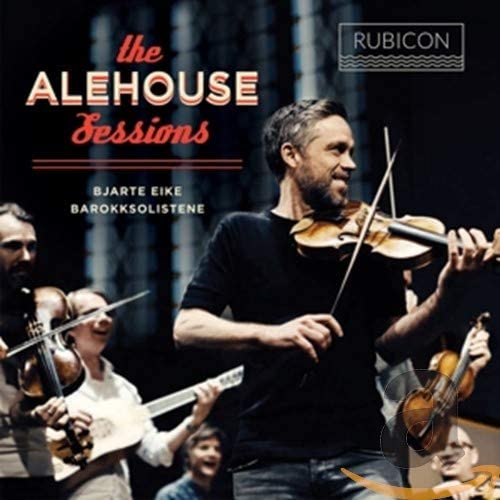

History first. The 17th century London of Oliver Cromwell and its puritanical quest to curb all creativity – banning music, closing down theatres, restricting alcohol and all the rest – provided an incredible backdrop for Barokksolistene’s project The Alehouse Sessions. How music survived with its tunes and tales, in song and dance, has for me been a true revelation.

The out-of-work court musicians mingling with the locals at London’s many public drinking houses created a huge amount of wonderful music. Defying prohibition and censorship, human creativity survived with creative people just being creative. New musical genres emerged, hybrids of traditional (folk) and composed (art) music, with catches (the drinking songs of "serious" composers) and bawdy ballads, using music as political satire. The public houses thus became true free spaces for artists and audiences alike.

During the Restoration that followed Cromwell’s Commonwealth, audiences were so hungry for the arts that theatres couldn’t be built fast enough. But after years of political divisions and civil war, Charles II, now on the throne, had very limited resources for culture, so public houses continued to flourish as the mainstay for musical entertainment.  Some taverns and inns, having a bit more space than the typical smaller alehouse, turned their backrooms into music houses. Ticket sales and subscriptions soon followed, paving the way for the first public concert halls. Some pubs went even further, building small theatres and raked seating. On these stages a mixture of plays, music, dance, opera and jesting were presented in masques, dumbshows, etc. These performances were probably closely related to the "stage jig", a type of short comic drama that immediately followed a full-length play in the early Elizabethan theatres of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

Some taverns and inns, having a bit more space than the typical smaller alehouse, turned their backrooms into music houses. Ticket sales and subscriptions soon followed, paving the way for the first public concert halls. Some pubs went even further, building small theatres and raked seating. On these stages a mixture of plays, music, dance, opera and jesting were presented in masques, dumbshows, etc. These performances were probably closely related to the "stage jig", a type of short comic drama that immediately followed a full-length play in the early Elizabethan theatres of the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

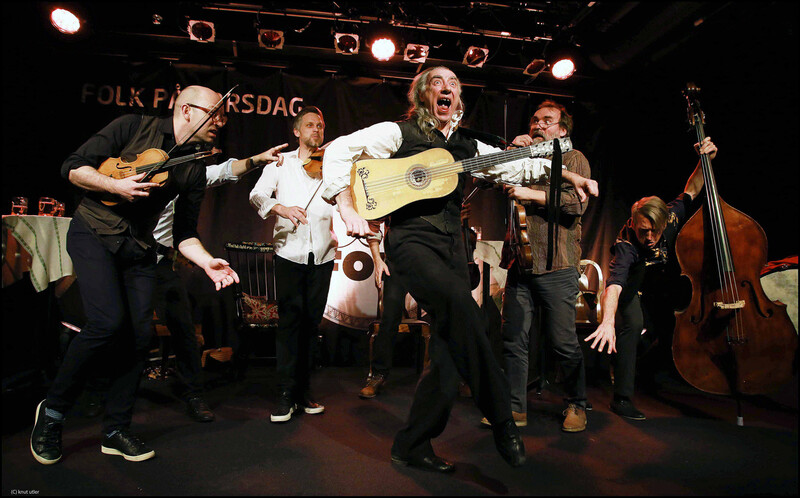

These theatrical jigs, also called "Elizabethan jigs", might include songs sung to popular tunes of the day, and would also feature dance, stage fighting, cross-dressing, masks and elements of pantomime. Jigs drew their plots from folk tales, jest books and Italian novellas and were often bawdy, sometimes satirical, but always with an emphasis on dancing and physical comedy. These sung dramas, or playlets, were populated by an assortment of traditional stock characters and tricksters, such as rustic clowns, fools and bawdy wenches (action scene pictuted above by Matthew.Long).

Performers like Richard Tarlton (died 1588) and Will Kemp (c.1560–1603) had made these jigs enormously popular and, though these light popular entertainments were banned in 1612, their reputation was insuppressible. One of the most famous and most popular tunes listed in John Playford’s The English Dancing Master (1651) is called "Kemp’s Jig".

And so a tavern’s backroom saw the happy marriage of Shakespeare, commedia dell’arte and juggling, with music by Purcell, folk tunes and sea-shanties. After a century dominated by the misery of civil unrest, plague and prohibition of everything remotely fun and pleasurable, audiences were hungry for entertainment! They were ready for a real party!

For years, I have had a real interest in exploring what it means to be a performing musician, to be on a stage. How should I behave when I have a violin in my hand? What is the difference between being a performing musician and a performing artist of any other kind? Why should I have to limit myself to only instrumental music? Could I consider myself more as a general performer, rather than just a musician? And what is the goal of the projects that take endless time to create?

For years, I have had a real interest in exploring what it means to be a performing musician, to be on a stage. How should I behave when I have a violin in my hand? What is the difference between being a performing musician and a performing artist of any other kind? Why should I have to limit myself to only instrumental music? Could I consider myself more as a general performer, rather than just a musician? And what is the goal of the projects that take endless time to create?

The music itself is important, of course, but what about the communication with the audience? How can a "normal’"concert be turned into a special event – something unique that only happens once – in a particular room, at a particular time – involving everyone present on and off stage?

"Showmanship" is not usually a favourable description of a musician’s character. But why is that? Surely, in our time, with everything the world has to offer within the touch of a screen, through the internet, streaming, social media, etc, shouldn’t creating the ultimate and authentic show, setting up true engagement between stage and audience, be the main goal of a live stage performer?

For me, there is no other way, and through the various shows we have created with Barokksolistene, we have gained a world of experience around the encounter between audience and performer.

Integrating elements of improvisation – both musical and theatrical – with storytelling and semi- staged scenes from operas, we dare to take risks: inviting audiences to sing with us, and letting them become the rhythm section. To involve, engage and explore has become the mantra of our BaS performances.(another live action scene pictured below by Knut Utler)

Increasingly over the last few years, we have become more theatrical with fully staged productions. We have been involved in multiple different versions of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas for various companies in Scandinavia, and the common thread of these diverse productions is the BaS musicians led by myself as the musical director, all always off-book and integrated as a part of the staging itself.  Towards the end of 2019, just before the pandemic, we staged a production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Haugesund Theatre in Norway. Together with stage director Erlend Samnøen I created a new script. Six prominent Norwegian actors and the BaS team from The Alehouse Sessions infused Shakespeare’s comedy with the atmosphere of the alehouse/playhouse world. The loft of Haugesund’s Staalehuset was transformed into a stage, with the audience invited in for drinks and a show – mixing the theatrical lockdown of Cromwell’s London with the story of MSND.

Towards the end of 2019, just before the pandemic, we staged a production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Haugesund Theatre in Norway. Together with stage director Erlend Samnøen I created a new script. Six prominent Norwegian actors and the BaS team from The Alehouse Sessions infused Shakespeare’s comedy with the atmosphere of the alehouse/playhouse world. The loft of Haugesund’s Staalehuset was transformed into a stage, with the audience invited in for drinks and a show – mixing the theatrical lockdown of Cromwell’s London with the story of MSND.

With the musicians appearing as the Athenian orchestra, the fairies and the Mechanicals, as well as themselves, the music became the central nerve to the story. The musicians created live soundscapes, mixed with music by Purcell (mainly from The Fairy-Queen), other Baroque composers and folk melodies, along with our own compositions. I appeared as Puck, Philostrate (master servant of Theseus, and the conductor of the court orchestra), and as the evening’s toastmaster, thus being the link between stage and audience, reality and make-believe, dreaming and waking, narrator and actor.

We performed excerpts of this show at one of our alehouse gigs in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at the Globe in London with the Norwegian text, which didn’t deter the London audience from going completely ballistic...

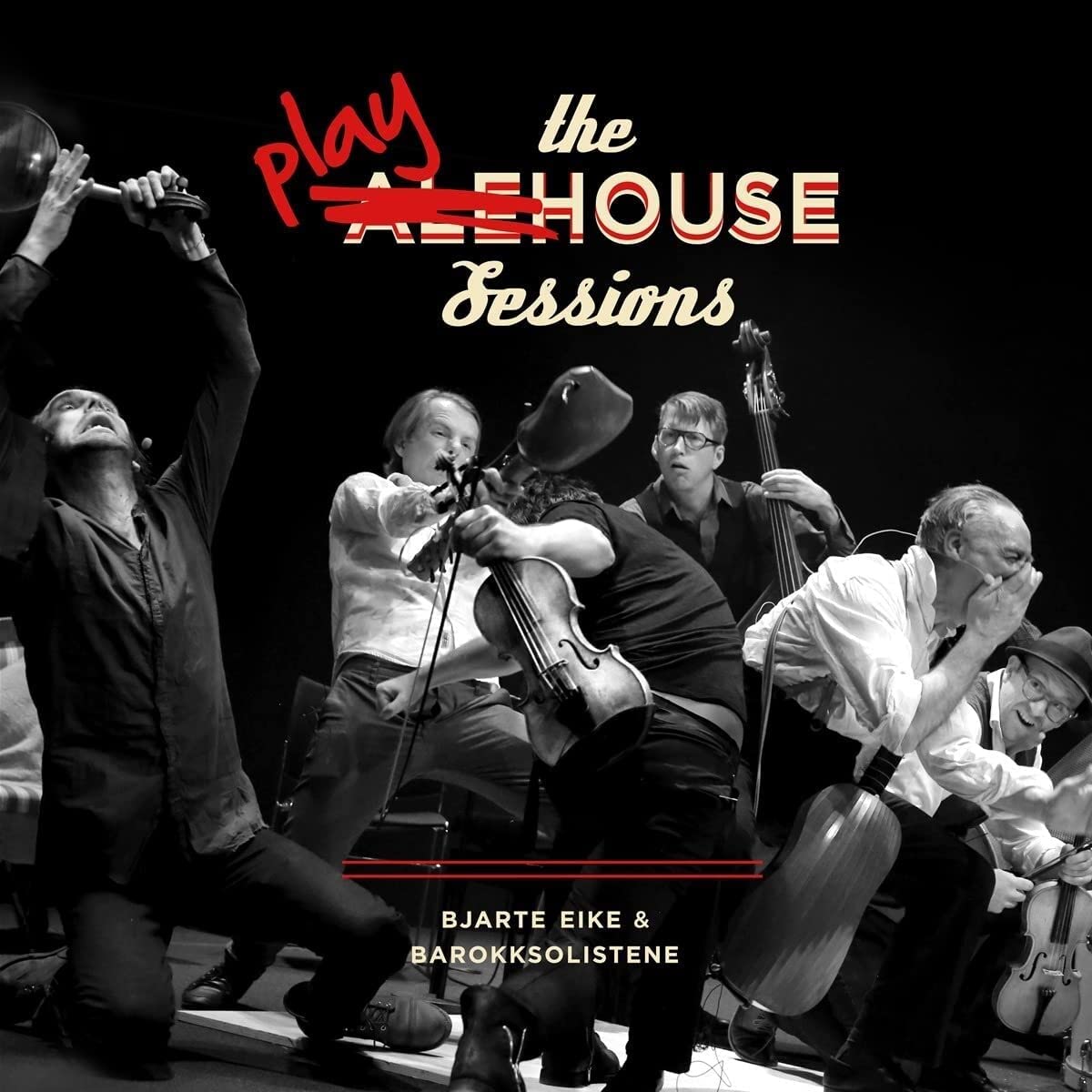

With these, and many other experiences behind us, it was inevitable that our next recording project would be The Playhouse Sessions: a follow-up to the irrepressible The Alehouse Sessions, without being a predictable Volume 2. It needed to expand on the narrative of the alehouse, to explore staged music, and dig deeper into Purcell, Shakespeare and broadside ballads. It has also given me the opportunity to compose my own music to familiar and unfamiliar texts and to update our storytelling.

What genre is the music in The Alehouse/Playhouse? The simple answer is that it defies borders and classification! It becomes a theatre of its own, using storytelling, humour, surprises, improvisation, touching melodies and much more.

My fascination for old melodies and the sound of historical instruments is still very much alive today. But I keep on wanting to expand, explore, challenge freely and creatively, while still using the discipline and expressions found within the early music field as tools of the trade. And with the unique constellation of the extremely curious, inventive and imaginative musicians we have in BaS, it simply isn’t enough just to reproduce scores or assimilate the way other early music ensembles approach the same kind of repertoire.

I wanted our new album to reflect how we work on stage. For instance, we recorded ourselves singing the choruses – playing and singing at the same time. We use several lead singers that join the ensemble – either singing or playing – when not doing the lead vocals. We always do our own arrangements of the music, and spend a lot of time fine-tuning/improving these through workshops, improvisational exercises, etc.

I wanted our new album to reflect how we work on stage. For instance, we recorded ourselves singing the choruses – playing and singing at the same time. We use several lead singers that join the ensemble – either singing or playing – when not doing the lead vocals. We always do our own arrangements of the music, and spend a lot of time fine-tuning/improving these through workshops, improvisational exercises, etc.

On this recording, I have also composed two of the pieces in their entirety. They are both from A Midsummer Night's Dream. In the play, both of these scenes are indicated as being sung, but as there is no surviving melody, I composed my own. Surviving Shakespearean melodies and broad-side ballads have been newly arranged and become distinct BaS versions, and we’ve of course included plenty of music by Henry Purcell. We also had to include some foot-stomping alehouse tunes (not previously recorded), and of course a real pub song for the singalongs.

In live settings, I see "The Playhouse" not as a new project, but rather a branch that grows out of the Alehouse tree. It gives me possibilities to highlight certain aspects - all depending on the situation we are in. So, in a staged production, or performing in a theatre, the narrative might be from the Playhouse - with elements from the Alehouse - And when performing in settings where it is more natural to do "The Alehouse Sessions", I might include stories and pieces from "The Playhouse". I see them more as part of the same project.

With our experiences of Covid, travel bans and general restrictions still fresh in mind, it is time for the Alehouse boys and girls to stand up from their alehouse barstools, move into the backroom and take their place on the makeshift stage – presumably with their glasses still in hand. Time to to party like it’s 1699!

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Add comment