theartsdesk in Lucerne: Simón Bolívar Meets William Tell | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Lucerne: Simón Bolívar Meets William Tell

theartsdesk in Lucerne: Simón Bolívar Meets William Tell

Venezuelans set the Swiss alight for Easter

Glaciers melted early this year when a Venezuelan army of well over 100 generals arrived in central Switzerland. The Swiss spring coincided with their visit, a gentle thaw with bees buzzing confusedly around the primroses, snowdrops and winter jasmine; but the first appearance of the now stellar Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela at the Lucerne Easter Festival was more like the violent icebreak Stravinsky said he had in mind for The Rite of Spring.

Abbado in Lucerne tends to bring out the superlatives. Transfixing even in his upbeat, the dapper Italian belied his 76 years and the fallout from his near-death illness, now some years in the past, with a hell-for-leather speed for Prokofiev's adoration of the pagan gods that would have taxed any orchestra. But the Sinfónica de la Juventud Venezolana Simón Bolívar, to give it the full name adopted in Lucerne, has now emerged from its rainbow-coloured chrysalis to become one of the top orchestras, regardless of age and origin.

In fact it's probably no longer so young; many of the players grew up with their star conductor, Gustavo Dudamel, in the fabulous educational sistema of 250,000 young musicians from all walks of Venezuelan life, instigated by the inspirational José Antonio Abreu and now giving a lead to the rest of the world. They could probably drop the "Juventud"; the sistema will continue to bring to light great players of the next generation. But they certainly haven't lost the passion which goes hand in glove with a new precision to make world-class music worthy of Lucerne.

The wealthy and beautiful town at the heart of Switzerland's lakes and mountains has its own superstar in the summer - the Lucerne Festival Orchestra which gathers for three weeks only, revitalised by Abbado in 2003 and made up of many of the world's best players, from members of the Hagen and Alban Berg quartets and cellist Natalia Gutman to a core of musicians from the Gustav Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Their Mahler is a miracle, and it was watching their first DVDs of Mahler and Debussy from Lucerne that convinced me I had to go and see them live.

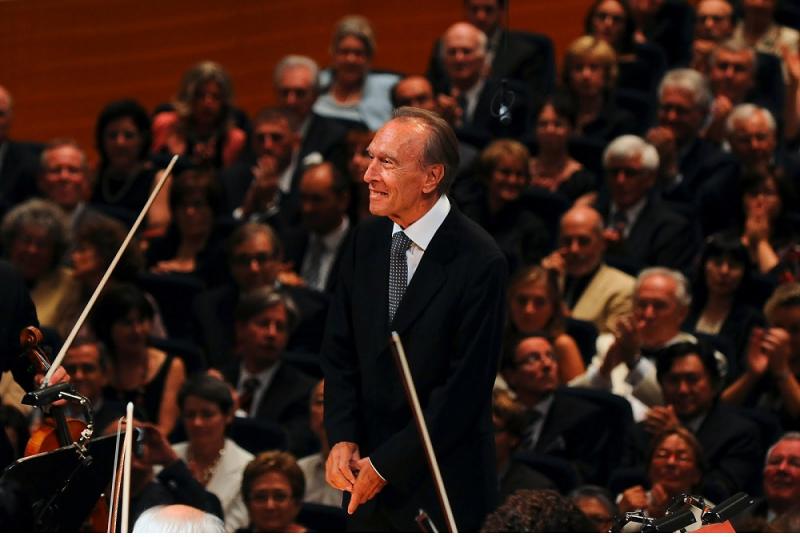

Abbado (pictured right with the Venezuelans in the first concert, photograph by Georg Anderhub) is now extremely selective in what and where he conducts. He still has the interests of the young very much at heart. It's because of that, and also because his doctor has told him the European winters make him lose too much weight following his illness, that he now spends the first two months of each year with the Simón Bolívar musicians in Caracas.

Abbado (pictured right with the Venezuelans in the first concert, photograph by Georg Anderhub) is now extremely selective in what and where he conducts. He still has the interests of the young very much at heart. It's because of that, and also because his doctor has told him the European winters make him lose too much weight following his illness, that he now spends the first two months of each year with the Simón Bolívar musicians in Caracas.

I spoke to orchestral contrabassoonist Aquiles Delgado, who grew up in the sistema with his pal Dudamel, backstage after the third in a chain of very different Lucerne concerts. He admires his friend Gustavo's long-term loyalty to the orchestra and his continued intensive training now that he's a superstar; and he points out that every conductor is an individual who brings something special to working with the orchestra. But he knows, as does Dudamel, that Abbado's current dedication has to be the best thing in the world, "because he now conducts so few orchestras, and he's chosen us. He's now in the last moments of his career, at the top of his Everest, and he knows more about music than any living conductor. That means we have to give to him everything we can. It's frightening because what he says he wants we have to do. Right from the first rehearsal he changes everything, not with many words, but with eyes and hands - dynamics, colours. And then in performance he changes even more. I don't know how, but we find a way. And because he lets you be free to show what you can do and he trusts you, it works."

Until Abbado came along, the Simón Bolívars had tended to stick to the big romantic works, delivered with panache, plenty of volume and a very distinctive sound from the Latin American brass section. He set them the task of Berg's Lulu Suite, a bigger challenge even than the Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky works flanking it in the first concert. It sounded like the most refined Debussy, bright and delicately sensuous, crowned by a stunning Lucerne debut from light but expressively intense soprano Anna Prohaska (pictured above with Abbado). Prohaska also gave us a swooningly lovely encore in Pamina's lament "Ach, ich fühls" from Mozart's Magic Flute, taken by Abbado at an authentically fleet speed which allowed her to unfold long melismas in a single breath.

Until Abbado came along, the Simón Bolívars had tended to stick to the big romantic works, delivered with panache, plenty of volume and a very distinctive sound from the Latin American brass section. He set them the task of Berg's Lulu Suite, a bigger challenge even than the Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky works flanking it in the first concert. It sounded like the most refined Debussy, bright and delicately sensuous, crowned by a stunning Lucerne debut from light but expressively intense soprano Anna Prohaska (pictured above with Abbado). Prohaska also gave us a swooningly lovely encore in Pamina's lament "Ach, ich fühls" from Mozart's Magic Flute, taken by Abbado at an authentically fleet speed which allowed her to unfold long melismas in a single breath.

Abbado's Tchaikovsky Pathétique Symphony was, predictably, a bel canto miracle of Italianate phrasing, the first movement's big melody an operatic aria without words. But even here I hadn't bargained for the sheer weight and, where necessary, elegance of the sound, with 12 double basses inscaping Tchaikovsky's final faltering heartbeat. To go from that to Dudamel's comparatively brash performance of the fraught fantasy-overture Francesca da Rimini the following evening was to discover Cinderella after the ball, having exchanged her splendid ballgown for practical working clothes. But Dudamel (pictured above in Lucerne, photograph by Georg Anderhub) is also a very serious maestro, no flashy boy wonder, and his interpretation of Strauss's Alpine Symphony in the second half was beautifully judged, with no expressive overkill on a firmly paced expedition up the mountain so that the phenomenal articulation of the Simón Bolívar could let rip with the torrential rain in the storm on the way down. They have big mountains in Venezuela, of course, but the players had experienced a Swiss alp for themselves on a previous visit to Lucerne, just to add a dash of authenticity.

Abbado's Tchaikovsky Pathétique Symphony was, predictably, a bel canto miracle of Italianate phrasing, the first movement's big melody an operatic aria without words. But even here I hadn't bargained for the sheer weight and, where necessary, elegance of the sound, with 12 double basses inscaping Tchaikovsky's final faltering heartbeat. To go from that to Dudamel's comparatively brash performance of the fraught fantasy-overture Francesca da Rimini the following evening was to discover Cinderella after the ball, having exchanged her splendid ballgown for practical working clothes. But Dudamel (pictured above in Lucerne, photograph by Georg Anderhub) is also a very serious maestro, no flashy boy wonder, and his interpretation of Strauss's Alpine Symphony in the second half was beautifully judged, with no expressive overkill on a firmly paced expedition up the mountain so that the phenomenal articulation of the Simón Bolívar could let rip with the torrential rain in the storm on the way down. They have big mountains in Venezuela, of course, but the players had experienced a Swiss alp for themselves on a previous visit to Lucerne, just to add a dash of authenticity.

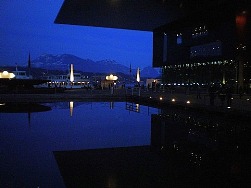

The concert auditorium lies at the heart of Jean Nouvel's KKL (Concert and Congress Centre Lucerne) complex (pictured left on the first evening of the Easter Festival), a fabulous construction with a spacious covered terrace looking out over the mountains and mirroring the waters of Lake Lucerne, which Nouvel brings inside the building via the water channels alongside the walkways. Some players I know have reported difficulties with the hall acoustics, not being able to hear their colleagues when the sound travels over the players' heads. But we all agree that as a spectator, at least, you can hear every detail, not least the most discreet cough on the other side of the auditorium. Aquiles described to me the "crystalline quality, which is very difficult because you can't hide anything. Gustavo encouraged us to really listen to each other in the Alpine Symphony, which is especially tough under those circumstances." It would have been hard on the players to demand an encore either after this or following Abbado's Tchaikovsky Sixth the previous night.

The concert auditorium lies at the heart of Jean Nouvel's KKL (Concert and Congress Centre Lucerne) complex (pictured left on the first evening of the Easter Festival), a fabulous construction with a spacious covered terrace looking out over the mountains and mirroring the waters of Lake Lucerne, which Nouvel brings inside the building via the water channels alongside the walkways. Some players I know have reported difficulties with the hall acoustics, not being able to hear their colleagues when the sound travels over the players' heads. But we all agree that as a spectator, at least, you can hear every detail, not least the most discreet cough on the other side of the auditorium. Aquiles described to me the "crystalline quality, which is very difficult because you can't hide anything. Gustavo encouraged us to really listen to each other in the Alpine Symphony, which is especially tough under those circumstances." It would have been hard on the players to demand an encore either after this or following Abbado's Tchaikovsky Sixth the previous night.

For that you had to return to the family concert on Sunday morning conducted by budding protégé of El Sistema Christian Vásquez, when parents and children lucky enough to snap up the 20 euro, kids-go-free tickets had replaced the elegantly dressed and rather frosty cream of Swiss high society. A violinist I know living in Lucerne felt sorry for the flag-waving Venezuelan settlers in the audience, doubting whether they ever got this kind of vital fix outside the Bolívars' visit. At least they got it at length, with Argentinian Ginastera's pulsing, colourfully-scored ballet dances as well as substantial native fare from Márquez and Castellanos. A serious tone was struck up at the start of the concert by the cello ensemble in Rossini's Overture to William Tell, the hero who pledged national resistance at the Rütli meadow near Lucerne; at the other end of a lively hour or so, players donned their trademark colourful jackets before hurling them into the audience and jigged around to the expected strains of the Mambo from Bernstein's West Side Story.

I really needed to adopt a child to qualify for admission, so I took my goddaughter's 13-year-old sister, who lives in Zürich. I asked her to write a short critique, so here are a few undoctored words from Maddy Dunscombe:

"The beginning of the William Tell Overture was wonderfully magical. It gave the feeling of suspense to what might happen next. Sinfónica de la Juventud Venezolana Simón Bolívar was probably the most awe-inspiring, lively and thrilling orchestra I have ever heard. One could really see how they put their life and soul into their instruments, in order to capture the audience. They did!

"The beginning of the William Tell Overture was wonderfully magical. It gave the feeling of suspense to what might happen next. Sinfónica de la Juventud Venezolana Simón Bolívar was probably the most awe-inspiring, lively and thrilling orchestra I have ever heard. One could really see how they put their life and soul into their instruments, in order to capture the audience. They did!

"I felt myself nearly pulled into the notes they played, and wanted to jump up and dance to the more rhythmic pieces. The orchestra played with such joy and enthusiasm. They left me utterly speechless!"

This is true: I know, because we had to strike out for a good 10 minutes along the lake before Maddy, clutching her Venezuela jacket, came out of her trance. Having delivered her to her father over lunch at Lucerne's Rathaus, I spent a reflective afternoon among the pre-Easter, purple-veiled splendours of the Hofkirche and walked a long way along the lake catching rainbows over the distant Mount Rigi before heading back to the concert hall for a very different event: two Beethoven cantatas I never, apart from a movement or two, want to hear again played with verve by the Concentus Musikus Wien under its ever-youthful 82-year old-guiding spirit Nikolaus Harnoncourt.

Maybe a more authentic Lucerne Festival spirit was on display here, but I found it hard to adjust. Not a view shared by the Venezuelan players in baseball caps and jeans who took up a few empty seats among the grey suits of the parterre, and who were the first to rise to their feet at the end of the concert. As for me, I hope to be back in the summer for Abbado's Mahler Ninth with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra - another predicted wonder of the musical world. I wouldn't travel anywhere else just to hear a concert, but Lucerne is special.

- The Lucerne Summer Festival runs from 12 August to 18 September

- Find Claudio Abbado and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra on DVD on Amazon

- See theartsdesk's European Festivals 2010 Round-up

Watch the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra under Dudamel at a previous Lucerne Festival, playing the Mambo from Bernstein's West Side Story:

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James’s Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James’s Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Add comment