Like his most famous creation, Billy Elliot, Lee Hall left his native North East to pursue what turned out to be a glittering career in the arts. Although I can’t speak for the fictitious Billy, Hall has certainly never forgotten his working-class roots, which continue to inform and inspire his work. This week sees the West End opening of The Pitman Painters, his highly acclaimed play based on William Feaver’s book of the same name which, following the original production at Newcastle upon Tyne’s Live Theatre, has enjoyed two seasons at the National Theatre, two UK tours and a season on Broadway.

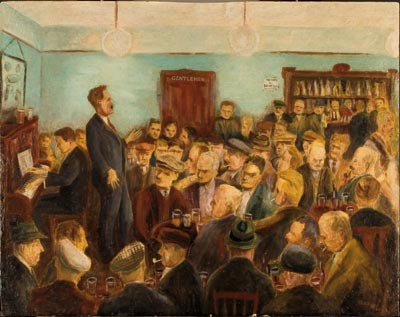

The Pitmen Painters is the true story of a group of miners from Ashington in Northumberland, who under the auspices of the WEA – Workers’ Educational Association – decided to study art appreciation. However, this was abandoned at the suggestion of their teacher, Robert Lyons, who persuaded them to take up painting and create their own work. The results were astonishing. The Ashington Group, as they became known, worked prolifically. They exhibited their work, which was collected by Helen Sutherland, one of the foremost collectors of Modernism at the time, were fêted by some of the most important artists of the day including Henry Moore, and were even treated to an evening of madrigals by the curator of the Tate. But every day they continued to work as before, down the mine (Pictured above: Saturday Night at the Club by Oliver Kilbourn, 1940.)

The Pitmen Painters is the true story of a group of miners from Ashington in Northumberland, who under the auspices of the WEA – Workers’ Educational Association – decided to study art appreciation. However, this was abandoned at the suggestion of their teacher, Robert Lyons, who persuaded them to take up painting and create their own work. The results were astonishing. The Ashington Group, as they became known, worked prolifically. They exhibited their work, which was collected by Helen Sutherland, one of the foremost collectors of Modernism at the time, were fêted by some of the most important artists of the day including Henry Moore, and were even treated to an evening of madrigals by the curator of the Tate. But every day they continued to work as before, down the mine (Pictured above: Saturday Night at the Club by Oliver Kilbourn, 1940.)

Hall was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1966 where he attended a comprehensive school, after which he went to Cambridge to read English. He came to writing rather later, but once he started, there seems to have been no stopping him. He has written several radio plays, several of which have been adapted for the theatre, such as I Luv You, Jimmy Spud (which was also made into a film called Gabriel and Me starring Billy Connolly), Cooking with Elvis and Spoonface Steinberg. This last was a truly audacious monologue spoken by a nine-year-old autistic girl who is dying of cancer – in one stage production it was performed by Kathryn Hunter, who was 42 at the time.

He has also penned several stage adaptations, such as Mother Courage for Shared Experience and Goldoni's The Servant of Two Masters for the RSC and the Young Vic and his screenwriting credits include Toast (BBC One), based on Nigel Slater’s autobiography, and War Horse, directed by Steven Spielberg and yet to be released. He will, however, always be most closely associated with the multi-award-winning film and musical productions of Billy Elliot, directed by Stephen Daldry, which, as he explains to theartsdesk, is intrinsically linked to The Pitmen Painters.

Looking back, I think I was amongst quite an extraordinary group of teachers, writers, theatre-makers

HILARY WHITNEY: How did your interest in theatre begin?

LEE HALL: I don’t really know. It must have been through school because my parents didn’t go to the theatre – the only time I remember going was to the pantomime – but I don’t think they ever watched any plays until they came to see mine. But whilst I was at school, there was a big movement of Theatre in Education and doing drama with kids – at least that was certainly the case in the North East. Dorothy Heathcote [former mill-worker-turned-academic who developed revolutionary ideas about using drama in education] was famously very influential and the main philosophy of all the teachers who used drama in education was about participation. We never, ever just put on a play; we either worked with a writer to put on a play – even at school – or more usually we’d devise work.

When I was about 13, along with some teachers, I wrote some songs for a musical about the cholera epidemic in Sunderland in 1831, so it seemed normal always to make stuff up and to learn through drama and for drama to be an expression of where you were and who you were. There was always a group of people you did it with and so it was much more about actual drama than theatre or literature or putting on plays. It was just something I did and because I enjoyed it, I joined the local youth theatre which was run on the same basis – you’d improvise and gradually a play would come out of it. During the miner’s strike we did a tour based around a Brecht play, The Fears and Miseries of the Third Reich, which we adapted into something relevant for the time. There was a great leader of the drama group, a writer called Steve Chambers, and he adapted it with us and looking back, I think I was amongst quite an extraordinary group of teachers, writers, theatre-makers who were very much wanting to come to working-class places – places that were deprived of a lot of cultural opportunity - and not just present art but make art with us.

As a result, there are several people from my school in the Pitmen cast. Trevor Fox, who plays Oliver Kilbourn, and Chris Connel who played that part before him, both used to go to my school and several of the company are also from the youth theatre I went to. I’ve known them since I was a teenager. So it wasn’t just me getting special education or these opportunities but a whole group of people. We come from a shared aesthetic and although we’ve all done things separately, we’ve all been formed through that experience and have the same attitude towards the work. (Pictured above: Ian Kelly, Trevor Fox, Brian Lonsdale, Deka Warmsley, David Whitaker and Joy Brook in The Pitmen Painters.)

As a result, there are several people from my school in the Pitmen cast. Trevor Fox, who plays Oliver Kilbourn, and Chris Connel who played that part before him, both used to go to my school and several of the company are also from the youth theatre I went to. I’ve known them since I was a teenager. So it wasn’t just me getting special education or these opportunities but a whole group of people. We come from a shared aesthetic and although we’ve all done things separately, we’ve all been formed through that experience and have the same attitude towards the work. (Pictured above: Ian Kelly, Trevor Fox, Brian Lonsdale, Deka Warmsley, David Whitaker and Joy Brook in The Pitmen Painters.)

It wasn’t until slightly later and through doing drama that I started to go to the theatre – because obviously I wanted to see what other people did - but doing it came first, rather than seeing it. That’s probably quite an unusual way round but it’s also quite good because even now I feel that I’m just doing what I’ve always done – making stuff up and working with a group of people. It’s like a hobby that I’ve done since I was a kid.

That’s rather like the pitmen in your play, isn’t it? They found the language to discuss art through the experience of creating their own work, rather than studying the history and theory of art.

Yes, they learnt from doing it and I think that’s why I was very attracted to the story of the pitmen because it was a sort of analogue for what we did. There was also the boisterous nature of the group combined with the sense of a common enterprise and trying to say something and understand the world through what you’re doing. It was very much part of how we made our work, a lot of which was based around Live Theatre [a theatre company specialising in new writing based in Newcastle upon Tyne], which was very influential. We went to see a lot of plays at Live Theatre because it was often North-Eastern writers writing about subjects that were very prescient to local people. It was very determinedly for everybody so its emphasis was on working-class people and their stories so we had a theatre that represented ourselves. We could go and we could see stories about our mums and dads and our families rather than seeing Chekhov and all of that – that came later.

It took me a while to realise quite how unique this micro-culture of Newcastle and the North East had been

So it was actually a very rich theatrical culture but one that didn’t seem very official. The RSC was posh theatre, proper theatre if you like, and it took me a while to realise quite how unique this micro-culture of Newcastle and the North East had been. There were some really interesting writers and practitioners who had been part of this. The two most influential ones I can think of were CP Taylor, who wrote Good. He would be writing a play for the RSC or a Play for Today, but also be working in a school, writing a play for them. He was the presiding influence over Live Theatre and there was also a guy who was a sort of elder statesman who died a couple of years ago called Tom Hadaway who, throughout all his life as a playwright, had been a fisherman and had a business selling fish, so the connection between people who worked and people who wrote and real life entering the theatre was a very porous one. Their plays were a very strong influence on us all and also they were very accessible. I never knew Cecil [CP Taylor] - he died before I really got involved - but Tom I knew quite well.

I think I was very lucky in having many mentors when I was very impressionable. A couple of years ago I might have described my narrative as being somebody from a comprehensive school who went to Cambridge and came out the other side saturated in dramatic literature, but now I realise that the influences that have lasted and have been crucial to my development were formed by the time I was 17 and were from Newcastle - actually working with writers and directors and actors right from when I was a kid. Again, I think that was quite unusual - it’s taken me a long time to realise that that isn’t normal.

So when you went to Cambridge what did you think you’d do? Did you think you’d be an actor or a director?

I guess I was interested in directing. I did direct a few plays when I was there, and I did a bit of acting as well, but I think that having always been part of this process of generating the material you would perform, I realised that just acting or just being a director and taking on somebody else’s work and putting it on was not what had motivated me in the first place, so gradually I got far more interested in writing and creating pieces of work.

So did you start writing at Cambridge?

No, I adapted – or I sort of adapted – an Aristophanes play that we did and that was the first time that I thought, oh, I quite enjoyed that. I liked the process of being at a desk and trying to work it all out. By the time I left Cambridge, I knew I didn’t want to be a director but I did know that I wanted to do something to do with theatre. I went back to Newcastle for a couple of years and did some work with some youth theatres - not very creative work, I have to say: a lot of organising and running sessions - and then I realised it was writing that I wanted to do. I think I was relatively late in coming to it, given that I’d been interested in drama from quite a young age. I was probably about 27 when I thought that I needed to give writing a proper go. I signed on the dole and decided to write some plays.

Didn’t your parents freak out – their Cambridge-educated son signing on?

I think they were very confused but I had a good sense that I thought it would somehow work out because I’d been saturated in thinking about it for years. I just thought, well, if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. But quite a few things came together at that time. When I’d been a student, I must have been about 20, I wrote some music for a production at the Sheffield Crucible and that’s where I first met Stephen Daldry who was there as a young director on a bursary. He had subsequently taken over the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill and I literally bumped into him in the street and re-engaged my friendship with Stephen and… (Picture above: Lee Hall and Elton John, who wrote the music for Billy Elliot The Musical, with the cast. Picture by David Scheinmann.)

I think they were very confused but I had a good sense that I thought it would somehow work out because I’d been saturated in thinking about it for years. I just thought, well, if I don’t do it now, I’ll never do it. But quite a few things came together at that time. When I’d been a student, I must have been about 20, I wrote some music for a production at the Sheffield Crucible and that’s where I first met Stephen Daldry who was there as a young director on a bursary. He had subsequently taken over the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill and I literally bumped into him in the street and re-engaged my friendship with Stephen and… (Picture above: Lee Hall and Elton John, who wrote the music for Billy Elliot The Musical, with the cast. Picture by David Scheinmann.)

That was quite fortuitous.

It really was. And he said, "Come and help out at the Gate," so I did. So when I was in this period of trying to work out how to be a writer, I was helping out there and through the Gate I met a theatre director called Kate Rowland who'd just become a radio drama producer. Kate suggested that I try and write for radio because it’s a very good place to start out as a writer – back then I think they used to produced 300 hours a year of drama – and so I thought, OK, I’ll give it a try, so all these things came together once I’d made the decision to write. I’d never heard a radio play in my life, I’d never listened to Radio 4 or anything like that, so I didn’t really know what one was, but I gave it a punt for my first play.

I had never in my life contemplated writing a screenplay, I literally didn’t know how to set one out

But you must have listened to a few before you wrote one?

No. I don’t know why, but I didn’t. I just wrote this play [I Luv You, Jimmy Spud] and Kate seemed to like it and then we made it with a lot of my friends who were actors who all came from this group in Newcastle and then I did another one and another one. It snowballed from there really, from my first radio play, because then somebody bought the rights to make it into a screenplay. I had never in my life contemplated writing a screenplay, I literally didn’t know how to set one out, so I went to the shop and bought a book and found out it had to be 120 pages long. Everything I’ve done really I’ve sort of stumbled into.

I spent quite a few years writing radio and film scripts – because somebody had got hold of the Jimmy Spud script in Hollywood and asked me to write some things for them and so I had this very weird career where I was writing radio plays as well as studio movies in Hollywood but still hadn’t got a play on and so I did a number of adaptations of plays for various people. There are several things I like about doing adaptations, one of which is that it’s really nice to learn from great playwrights and find out what they did it and how it works underneath the bonnet. Also, in the theatre, as a writer you’re on the other side of the interpretive artists – the director, the designer, the actors – all these people are on one side of the room and then there’s the creative person who’s making it all up on the other. It sort of has to be like that, a dialogue or tug of war between those two, but what’s great about doing adaptations is that you’re absolutely on the same side as the interpreters, you’re trying to find out how to put this thing on. Sometimes the writer, usually because they haven’t been able to articulate yet exactly what they are trying to say, is often in a defensive position about their work, whereas if you’re adapting something it’s a much freer process in the rehearsal room and it’s a very useful one.

Writing original plays takes so long that actually it’s very helpful to be in a rehearsal room with the group of people who are putting on the play. One learns so much from directors and actors, how they work, how they think, and I put myself into the rehearsal room as much as I possibly can because it’s very helpful for writing. And the more and more I go on, the more and more I understand that all writing is a massive collaborative process, especially for the theatre.

But it isn’t so much in television – well, British television at least.

The thing with television and film is that it’s all a bit chopped up and you do things in different bits because it costs so much to get everybody together at the same time in telly or film. That’s the beauty of theatre, that there’s the space that allows you to build something together and I’ve just been so lucky to have this group of Geordie actors I work with again and again. That’s an increasingly rare thing for a writer to have - a group of people that you’ve been on a journey with and have a common enterprise.

You must have your own kind of shorthand.

Yes, and we all know a lot about what people can do, so that’s very useful for me, to be able to write to their strengths but also, there’s a commitment to making something work because I think if you’re just meeting together for one production and then parting, there isn’t the same commitment to each other. You can’t make that up and once you’ve spent 10 – 20 years, now – in and out of each other’s creative lives, as well as our real lives, of course, that’s… I don’t know how it’s different, it’s probably different in a million different ways, but I realise that it’s a very rare and precious commodity to me and my work. (Pictured above: David Whitaker, Brian Lonsdale, Michael Hodgson, Trevor Fox, Deka Warmsley in The Pitmen Painters.)

Yes, and we all know a lot about what people can do, so that’s very useful for me, to be able to write to their strengths but also, there’s a commitment to making something work because I think if you’re just meeting together for one production and then parting, there isn’t the same commitment to each other. You can’t make that up and once you’ve spent 10 – 20 years, now – in and out of each other’s creative lives, as well as our real lives, of course, that’s… I don’t know how it’s different, it’s probably different in a million different ways, but I realise that it’s a very rare and precious commodity to me and my work. (Pictured above: David Whitaker, Brian Lonsdale, Michael Hodgson, Trevor Fox, Deka Warmsley in The Pitmen Painters.)

So when did you manage to get your first play on stage?

Cooking for Elvis was my first stage play which was an adaptation of a radio play that I wrote and I think that was in about 1987, and then several of my radio plays were made into stage plays, but I would say that The Pitman Painters is the first absolutely grown-up play that I’ve written for theatre which again, as a writer, it’s quite late – you know, to be in your forties before you write your first play. Of course, I’d done a lot of adaptations of both my own work and other people’s but although I’ve written a lot for the theatre, I’d never call myself a playwright. I’m more of a dramatist, because whatever I’m writing I deal with characters, dialogue and drama. But I do feel quite at home in the theatre. I’m very happy there.

I’m very intrigued by Spoonface Steinberg. Wherever did you get the idea from and did you ever think when you were writing it, oh, I’m not going to pull this off?

Well, it was very odd. I’d written the Jimmy Spud play and realised I was really writing about myself and my own childhood - a very fantastical version but my dad had been ill when I was a kid and I’d always wanted to write about that - so I made up this story about a kid who’s dealing with his dad’s illness but there was a theme running underneath it about faith and I started writing a quartet of plays about kids and faith. I knew that I wanted to write about a Jewish kid and I spent a week with a very famous avant-garde theatre director, an American called André Gregory, who was in the movie My Dinner with André, and he was telling me about the Hasids in Poland, their whole tradition and the works of Rabbi Nachman and Martin Buber and I got very fascinated by this mystical Jewish tradition and all these ideas came at once. It was like automatic writing - I wrote it over two days and it’s the only thing I’ve written quite that fast, so I never really considered whether it would work or not. As it was coming out, I knew it was absolutely barking mad to try and do a monologue with a nine-year-old for an hour as a stream of consciousness and had I stopped to consider it seriously when I was writing it, it would have seemed just too daft, but I didn’t. I thought Kate Rowland, the producer, was going to baulk at this ludicrous script, but she was brave enough to say, “OK, we’ll go and find a nine-year-old,” and was able to work with Becky Simpson and make this radio play which was very beautiful and arresting. It was quite potty when I look back on it but because it worked it also gave me the confidence to follow my nose. But to be quite honest, all of those things [the quartet of plays] seemed like the most natural things in the world to write. They didn’t seem odd when I was writing them at all.

So Spoonface Steinburg was a firm commission?

Yes. You do have to give a rough idea of what you’re going to do but when I got the commission, all I knew was that it was going to have a kid in it and it was going to be about Judaism and that was about it, but because I’d already had a couple of successful plays, they trusted that I would deliver something OK. But the beauty of radio is not that you get a commission, because there are many commissions in theatre and television, but that in radio you get a commission with a production attached so you know it really is going to happen. So you’ve got to learn how to deliver the scripts on time, you’ve got to learn the discipline of criticising yourself, getting a draft into shape, writing, rewriting, working with the producer, getting used to the casting process.

I’ve now learnt that getting the play on is just the first part of the journey and then inevitably I want to rework it

During my first few years of writing I wrote six or seven radio plays which I think would have taken me six or seven years for the theatre so it was a brilliant opportunity to just get used to being a proper grown-up writer because I think there’s a whole side of theatre, and especially TV, which is all about getting stuck in development. You go round and round and I don’t think, as a writer, you can really properly learn until you get in front of an audience. Many, many theatre people will tell you this but you don’t really know what you’ve got until the first night, the preview night, when people come and you suddenly see the whole thing differently. I’ve now learnt that getting the play on is just the first part of the journey and then, inevitably, I want to rework it and even now, I rework little bits of The Pitmen or Billy Elliot. I can only make very small changes now but for the first few years of both of those projects, I’d be constantly writing new scenes or changing things round and driving everybody mad but that’s one of the great things about having a group of people who trust you and you can trust because we share the work in that way. It’s something we’re trying to get right together and all of the people I work with are completely unselfish about the play being more than any one of us.

Had you heard of the Ashington Group before you read William Feaver’s book?

No, I hadn’t. I was on the Charing Cross Road in Shipley’s which has now sadly gone - it used to be this fantastic art bookshop - and found this book, The Pitmen Painters, and I took it off the shelf because it seemed like an oxymoron: how could this be? So I bought it, read the first chapter on the way home, realised it was a brilliant story for m e and I rang up Max [Roberts, artistic director of Live Theatre and director of the play] and I said, “I think I’ve found my play. I haven’t read the whole book yet, I have absolutely no idea what happens, but…” I just knew immediately. I think that more than the pitmen wanting to become artists, I was attracted to the idea of a group discovering and discussing art and I’d been looking for a play where you could talk about something. I’ve written a lot of screenplays and it’s very hard to have sustained talking in screenplays. You are always encouraged to take lines out, everything is in the subtext and nothing is very talky, so I was quite desperate to write something that could have a discussion. And of course it was set in the North East and so lots of things came together. It was very apposite for my interests. (Pictured above: Committee Meeting by Harry Wilson, 1937.)

e and I rang up Max [Roberts, artistic director of Live Theatre and director of the play] and I said, “I think I’ve found my play. I haven’t read the whole book yet, I have absolutely no idea what happens, but…” I just knew immediately. I think that more than the pitmen wanting to become artists, I was attracted to the idea of a group discovering and discussing art and I’d been looking for a play where you could talk about something. I’ve written a lot of screenplays and it’s very hard to have sustained talking in screenplays. You are always encouraged to take lines out, everything is in the subtext and nothing is very talky, so I was quite desperate to write something that could have a discussion. And of course it was set in the North East and so lots of things came together. It was very apposite for my interests. (Pictured above: Committee Meeting by Harry Wilson, 1937.)

You'd been commissioned to write a play for the opening of Live Theatre’s new building, hadn’t you?

Yes, I’d promised to write the first play for the new building and I had various ideas but none of them were really going to work so this came out of the blue and saved me. Thinking about it, I had vaguely heard of the Ashington Group, I must have seen them on the telly or something when I was a kid, although I must have been very, very young because there is one film of them from the very early Seventies and I must have seen that on the local news or something. But I didn’t really know very much about them and they had all died by then, so I contacted Bill Feaver and said, “I want to write a play about these guys.” Oliver Kilbourn had left Bill his archive and he lent me the notebooks the group had kept where they’d write down little comments about what Robert Lyons was saying and Bill also has a lot of their paintings and was just incredibly helpful and generous with his time.

But there must be some of their children and grandchildren around?

There are children around but they are not up in Ashington and quite a few of them now live abroad, so until we actually put the play on I never had the chance to talk to them. But through Bill and through other people in Ashington who did know them, I got a kind of sense of who they were. Of course, there were a lot more in the original group so I gradually boiled it down to what I thought were the representative, the strongest figures and I think that they were the figures that lasted the longest.

I knew that if you got the play right, it couldn't fail to be moving because actually what they were doing was quite extraordinary

The Pitmen Painters' title is a bit like that perfect film pitch, Snakes on a Plane - you understand exactly what it’s going to be about straight away, but it must have been quite difficult to write. It’s a fantastic premise, but it’s not actually that dramatic, is it? It’s very interesting, and crammed with ideas, but there’s not much in the way of action.

No, there isn’t and it was a very hard play to write because nothing happens essentially. It’s like watching paint dry! But I knew thematically that it was absolutely charged with a lot of things that are very current and that they were incredibly passionate and I knew that if you got the play right, it couldn't fail to be moving because actually what they were doing was quite extraordinary.

Yes, and after a long hard day at the pit.

And they did it for 40 years, which was an incredible thing. Their commitment to each other was unimpeachable and what they achieved was unique. There are some individual pieces of work which are very beautiful and very evocative and extraordinary - if you go to the museum on the site where their pit used to be, there are pictures all up to the ceiling - but really, the legacy in the whole of this mass of pictures is that it’s a unique record of working-class life. Of course, it’s a life now that is dying out but it’s certainly the one I grew up in - their pictures were just like my granny’s house and everybody in the company, they knew people like that.

I find it really touching the way they all scrubbed up and put their suits on to go to their classes.

I know, almost like going to church. I don’t think I ever saw my grandad, who worked in a factory, without a suit and tie on. So there is the pride and ritual of their coming together. I think that their group was highly unusual but also absolutely typical of what was happening through the unions and the WEA at the time - that whole movement about working-class self-improvement and education. There was also this idea that they mention in the play, praxis, which is that you learn about the world through what you do and that the theory and the practice is indeed the same thing. It’s a Marxist idea and I do think, going back to what we started talking about, that the practice of learning about the theatre and life was always for me the same thing. It was creative and I had fun but it was also learning about something and commenting on other people’s ideas. It was all part of this conversation that I was having with other people and myself and it seemed to me that they [the pitmen] were exemplary in that sense, that somehow they were creative in their criticism and their creative works were indeed very critical about the world. (Pictured above: Trevor Fox, Deka Warmsley, David Whitaker, Michael Hodgson, Brian Lonsdale and David Leonard in The Pitmen Painters.)

I know, almost like going to church. I don’t think I ever saw my grandad, who worked in a factory, without a suit and tie on. So there is the pride and ritual of their coming together. I think that their group was highly unusual but also absolutely typical of what was happening through the unions and the WEA at the time - that whole movement about working-class self-improvement and education. There was also this idea that they mention in the play, praxis, which is that you learn about the world through what you do and that the theory and the practice is indeed the same thing. It’s a Marxist idea and I do think, going back to what we started talking about, that the practice of learning about the theatre and life was always for me the same thing. It was creative and I had fun but it was also learning about something and commenting on other people’s ideas. It was all part of this conversation that I was having with other people and myself and it seemed to me that they [the pitmen] were exemplary in that sense, that somehow they were creative in their criticism and their creative works were indeed very critical about the world. (Pictured above: Trevor Fox, Deka Warmsley, David Whitaker, Michael Hodgson, Brian Lonsdale and David Leonard in The Pitmen Painters.)

Politics and art were very intertwined which I thought was very interesting, especially as it seems that for a long time, especially during the Blairite years, that class was supposed to be off the agenda – well, it was off the agenda and sometimes it was said that we had gone into this classless realm and for anyone who lives in this country to say that is just preposterous. Preposterous! What had been such a mainstay of so much dramatic and literary activity and culture, this idea of talking about class and representing what it was like to live, was being short-changed. I always felt passionately that people would want to talk and think about that because so much of our everyday existence is permeated by a lot of these divisions and I thought what was interesting about this group is that they were examining all that. Particularly interesting to me was that you had this teacher who was ostensibly, to them, very posh but there was this meeting of these two different cultures and something quite fantastic came out of it. I don’t think those guys could have done it without meeting and working with this person from another class and so I think it celebrates working-class life and culture in a way, I think, that is not often done. It celebrates its intellectual past and its traditions but – and this may not seem obvious but it is very important to me and the company - it is also celebrating what I saw happen to me, which was people deliberately trying to come and teach and change and make a difference. An important speech in the play is where Robert Lyons says to Oliver, “Art isn’t enough, you’ve got to go into the world and change things.” He basically says that the working class have got to get off their arses and make something in this realm because I think that if you exempt yourself from the realm of culture and just become a consumer of culture, we leave ourselves very vulnerable as a society.

There is a utopian spirit in theatre, and certainly in folk music, where what matters is the art and it’s a great leveller

Also their identity is so bound to the idea of their work being miners, isn’t it? When Oliver is given the choice to leave the pit, he says he wouldn’t know who he was if he didn’t work down the mine. Was he really given that choice?

That’s my main intervention in the real story. I kind of squashed it into an event but it was very clear that he made a positive choice to stay. But it seems to me that my journey and a lot of my friends’ journeys have meant that we have left our class. We don’t do working-class work – we do artistic work – and so we’ve done that thing of getting out of our class. But I think that my friends from Newcastle, I think they set themselves apart from a lot of other actors because they don’t feel middle class. They do middle-class work and they have slightly middle-class lives but, I think, they feel slightly apart from the ordinary acting fraternity. I think that’s also true of a lot of northern actors, certainly in Scotland and in Yorkshire and Manchester - actors who work there think of acting much more like an ordinary job and what was very interesting about the pitmen was that they couldn’t see why you couldn’t be a proper artist who was treated like a proper artist and still do whatever you do – whether you’re a judge or a bank manager or a pitman.

It’s always been considered absolutely normal to be a Reverend so and so and to write Tristram Shandy or be a hack journalist and be a novelist - white-collar work has always existed with creative work, it doesn’t seem a juxtaposition - but working-class people and creative work seems to be a very unusual thing and I think that the pitmen didn’t see that, they didn’t see why they couldn’t do both. I know that for me, another influential thing for my creativity was that I used to play the fiddle - I still play the guitar and mandolin and stringed things - but I was quite into folk music and what was interesting about that was, as not so many people could make a living out of folk music, most of folk music was played by people who did other jobs. You may be a bus driver or you may be a teacher or you may be something else and I remember, when I was about 12, going to hear this unbelievable flute player from Ireland and someone else mentioned he was a bus conductor from wherever he was from and I just couldn’t believe it. He’d just won the All Ireland Championships or something like that and it made a big impression on me – to discover that anybody could do art and could be part of that life, and folk music really is like that. And if anyone plays the fiddle or the flute that well, it’s possibly the most important thing in their life because that’s what defines them – their creativity, not their job.

But both folk music and the theatre are places where the class divisions are very blurred. What I love about a rehearsal room is that you might have a Lord’s son who’s been to Eton in one chair and a miner’s son in another and sometimes the miner’s son will have a posher accent than the guy who went to Eton. But in a very small way, there is a utopian spirit in theatre, and certainly in folk music, where what matters is the art and it’s a great leveller. I think that’s why I feel at home there because I think that all the complexities of class – I mean, they don’t disappear, there are always tensions, but the prime objective is to ignore all the stuff that’s unimportant because you’re trying to use whatever you can bring to make something else, to make something different that transcends all that. I do see theatre through rose-tinted spectacles in that sense because I think there is a democratic and utopian element there that’s very valuable and I want to be part of.

The mining community is so different to the one you portray in Billy Elliot - the idea of trying to improve yourself and wanting to find out about the world doesn’t exist.

That’s another one of the reasons I wanted to write the play – in a sense I thought of it as a prequel to Billy Elliot. I was trying to raise the question, rather than answer it, as to why there had been these guys, many of whom had managed to be part of a movement that had nationalised their industry, preserving it for the common people and the common wealth of the nation and then 40 years later, there was a boy who wanted to pursue high art who was pilloried at a time when the government was basically trying to crush the commonly held property for the nation and wrest it from the hands of the people into private ones. And reading and understanding that that moment just after the war, with the Labour government and all that was happening in education and that fantastic utopian will, inspired by certainly the socialist notion of how we might live and what should be held in common, seemed to have been smashed. (Pictured above: Josh Baker as Billy Elliot and Genevieve Lemon as Mrs Wilkinson in Billy Elliot The Musical. Photograph by Alastair Muir.)

That’s another one of the reasons I wanted to write the play – in a sense I thought of it as a prequel to Billy Elliot. I was trying to raise the question, rather than answer it, as to why there had been these guys, many of whom had managed to be part of a movement that had nationalised their industry, preserving it for the common people and the common wealth of the nation and then 40 years later, there was a boy who wanted to pursue high art who was pilloried at a time when the government was basically trying to crush the commonly held property for the nation and wrest it from the hands of the people into private ones. And reading and understanding that that moment just after the war, with the Labour government and all that was happening in education and that fantastic utopian will, inspired by certainly the socialist notion of how we might live and what should be held in common, seemed to have been smashed. (Pictured above: Josh Baker as Billy Elliot and Genevieve Lemon as Mrs Wilkinson in Billy Elliot The Musical. Photograph by Alastair Muir.)

And obviously - well, it was obvious to me, that it was a riposte to a lot of what I think is the wrong-headedness of New Labour’s view of the role of the state and the role of class and education. I felt very strongly that it was a way of raising some questions about what we have lost. Something’s gone completely wrong in the sense that more people are getting higher education and yet we are more and more dumbed down. There seems to be an incredible paradox about material affluence and… somehow, something went terribly wrong. Of course, with Billy Elliot, it was that great political intervention of Thatcherism and that brutal campaign [against the miners] but a lot of the thinking that went into the New Labour project threw out the baby with the bath water and I really lament how the working class have accepted culture being ripped from them. Now it is all about this process of becoming a consumer and you’re seen in this passive role and the one thing you have to be if you want to make art is active.

I think that, ultimately, what The Pitman Painters is about is summed up in the speech about an abstract work of art being a document of somebody’s labour, almost a very purist document of labour, and that labour is, in the Marxist sense, where value is. Because it is so abstract, you can only read what it is about when you strip away its powers of representation and are left with this very primal act of creativity - where the work of the artist and the work of the artisan meet. That seems to me to be an incredibly important idea to foster, given the huge forces that are trying to neuter everyone to become the perfect consumer – and, of course, the perfect consumer is always seen as an individual and not as a group because the group might support each other and people might start getting ideas of their own. Ordinary people can make art and they can make politics and they can make things better – and it seemed that these guys were metaphors for all of those things.

- All production photographs of The Pitmen Painters by Keith Pattinson

- The Pitmen Painters opens at the Duchess Theatre on 5 October

- Billy Elliot The Musical at the Victoria Palace Theatre is currently booking until 15 December, 2012

Add comment