Ian Bostridge, Antonio Pappano, Wigmore Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Ian Bostridge, Antonio Pappano, Wigmore Hall

Ian Bostridge, Antonio Pappano, Wigmore Hall

Schubert's Schwanengesang sung with meticulous elegance and dramatic integrity

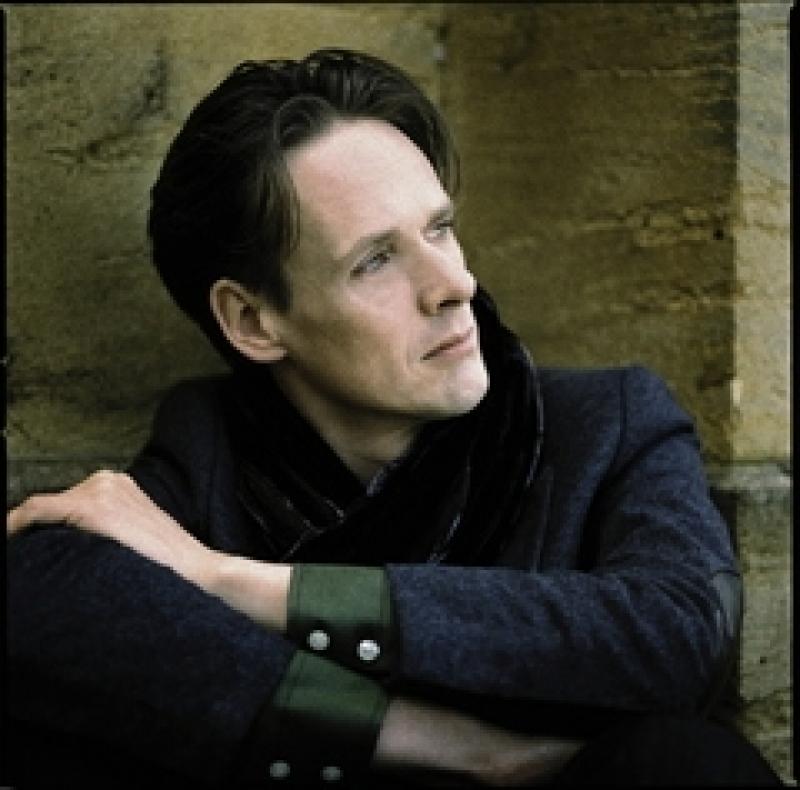

Ian Bostridge is one of those artists – Andreas Scholl is another – whose technique is so suited to the recording studio, his recordings so ubiquitously loved and lived-with, that the opportunity to see him perform live has become one of conflict.

Last night’s performance of Schubert’s late songs – the programme released on CD by Bostridge and Antonio Pappano last year – saw this battle played out for the favour of an adoring capacity crowd. Cracks and breaks there were, even some bizarre straining in the lower register, but the honesty and terrifyingly committed vulnerability on show was, on balance, more than compensation for the loss of studio sheen.

A soldier sleeps among his comrades, dreaming of his beloved; a man stands transfixed outside the house that once belonged to his love; a would-be lover calls to a fishermaiden, urging her to come ashore to his arms. Schubert’s Schwanengesang is not a song cycle in any conventional sense, rather a set of variations on an emotional theme. More reflective than Die schöne Müllerin, less starkly monochrome than Winterreise, it’s a work well suited to Bostridge’s particular expressive talents.

With Covent Garden’s music director Antonio Pappano moonlighting at the piano, he negotiated his way along the delicate paths of Schubert’s late songs with the meticulous elegance that has become his trademark. Restrained, inward, but never unemotional, Bostridge is one of the most generous of musical interpreters. In a contest between vocal beauty and dramatic expression, he will consistently opt for the latter, ego set aside for the greater good of the music itself.

It’s a brave approach, and one that paid off particularly in Schubert’s more histrionic atmosphere pieces. His rendition of “Der Doppelgänger” – Heine’s chilling vision of a man contemplating his own helpless enslavement to memory – was uncomfortable in exactly the right way, raw and daringly edgy of tone. His ability to invest a consonant with emotion is second to none, and even tuning – so often treated in rustic fashion as a binary of correct/incorrect – becomes in his hands a far broader spectrum, exploiting the emotive and harmonic power of manipulating pitch to the extreme ends of its in-tune range, drawing attention to Schubert’s own harmonic experimentation.

Yet Bostridge’s attention to detail can also work against him, as was evident in the many briskly jaunty numbers within the cycle. Such is his desire to convey the nuances of text and musical intention that – as with Bryn Terfel – you occasionally lose the over-arching line of a phrase. Combined with some rather bulging moments of vocal production, the effect can at times becomes a little too emphatic, a little too studiously micro-managed. It also has impact on broader interpretational gestures. The subversion and irony present in so many of the poems and their musical settings (much stressed in Richard Stokes’ excellent programme notes, which urged us to reconsider traditional interpretations of classics such as “Ständchen” and “Das Fischermädchen") didn’t quite translate in performance, caught behind the filter of Bostridge’s earnest sincerity.

Others have praised Pappano’s accompaniment unreservedly, but while his sympathy and musical partnership with Bostridge was evident, I couldn’t help feeling that his technique was hindering him from fully realising his understanding of the music. His use of the sustaining pedal in particular seemed bizarrely indiscriminate, masking the clarity of Schubert’s dense piano writing, and jangling in its broad-brushstrokes approach with Bostridge’s fastidious attention to detail.

There are faults to be found, particularly under the glare of the concert hall lights, but it’s hard to shake the gut sense that, sitting in a Bostridge recital, you are listening to Lieder as they ought to be sung. Others may possess a greater range or greater vocal power, but for musical understanding Bostridge is still unsurpassed.

- See the Wigmore Hall's plans for next season

- Bostridge and Pappano repeat their performance at the Wigmore on 31 May. Book tickets here

- Find Ian Bostridge CDs on Amazon

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Comments

...