Interview: Michael Winner on collecting Donald McGill | reviews, news & interviews

Interview: Michael Winner on collecting Donald McGill

Interview: Michael Winner on collecting Donald McGill

As the seaside postcard makes it to the Tate, a famous collector explains the allure

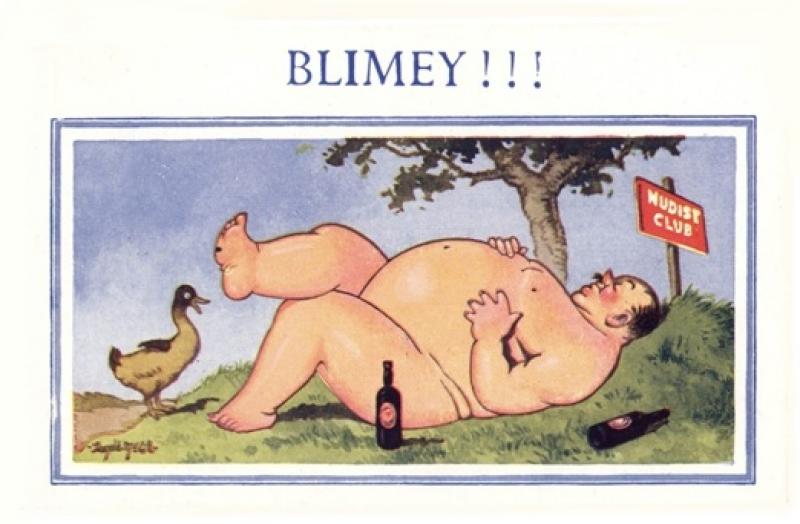

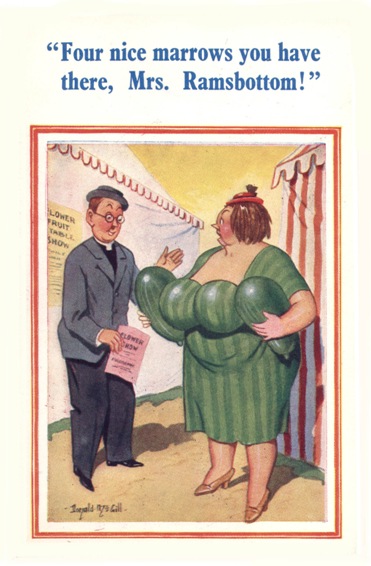

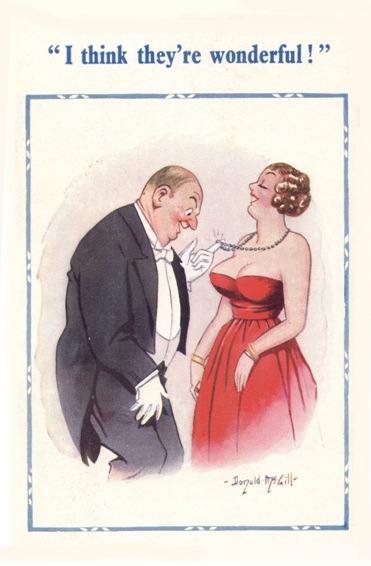

This week a new exhibition with no pretence to seriousness opens at Tate Britain. Rude Britannia: British Comic Art is a comprehensive tour of a great national tradition: having a laugh in a line drawing. The show covers the boardwalk from Gilray and Cruikshank to Gerald Scarfe and Steve Bell. It also includes the work of a cartoonist and illustrator whose world view, more than any other, now seems deliciously quaint and old-fashioned: Donald McGill.

It's not widely known that the greatest collector of McGill's in this country is the film director and bon viveur, Michael Winner. A couple of years ago he put his McGills on the market, and I went to meet him to find out precisely why the man who made Death Wish, Death Wish II and indeed Death Wish III had a soft spot for the saucy dauber of seaside postcards.

Winner's house on the southern edge of Holland Park in London is in what was once a wealthy artists' ghetto. Luke Fildes, one of several Victorian painters domiciled in this quiet row of villas, painted Edward VII there. Nowadays Jimmy Page lives next door. And beyond him is the recently reopened Leighton House. When Winner shuffles off his mortal coil, the road will offer tourists a choice of houses to visit: he is leaving his, designed by Norman Shaw, to the nation, with its bulging collection of art. There’s not a spare patch of bare wall in the bedroom, on the grand staircase, in the receptions, in the loos. And the projection room is lined floor-to-ceiling with photos of all the stars from the owner’s years as a film director: Winner with Brando, Winner with Welles, Winner with OJ…

Winner's house on the southern edge of Holland Park in London is in what was once a wealthy artists' ghetto. Luke Fildes, one of several Victorian painters domiciled in this quiet row of villas, painted Edward VII there. Nowadays Jimmy Page lives next door. And beyond him is the recently reopened Leighton House. When Winner shuffles off his mortal coil, the road will offer tourists a choice of houses to visit: he is leaving his, designed by Norman Shaw, to the nation, with its bulging collection of art. There’s not a spare patch of bare wall in the bedroom, on the grand staircase, in the receptions, in the loos. And the projection room is lined floor-to-ceiling with photos of all the stars from the owner’s years as a film director: Winner with Brando, Winner with Welles, Winner with OJ…

If there are two themes to Winner’s extensive collection, they are Venice – there are canal views up and down the house – and children’s literature. He has sundry originals by Edmund Dulac, EH Shepherd and Arthur Rackham. But until recently there were some works in the collection which had never seen the light of day. Over many years Winner gathered nearly 200 signed colour-washed illustrations by Donald McGill. It may well have been the largest private collection in the world. But he somehow never found the space to show them all off and they were eventually sold through the Chris Beetles Gallery in central London.

“Only one was ever displayed,” Winner told me. “It was two girls with big bosoms. They were saying something quite funny to each other. I didn’t have anywhere to put them, so I kept putting them in a drawer and they sat in a drawer for 25 years, some of them, wrapped up in black plastic bin liners. And of an evening I'd take them out like Fagin taking out his jewellery and look at them and put them back in. It seemed to me, that’s no life for a work of art. It’s not right. If I’m not getting the full value…”

The full value will surprise anyone reluctant to see McGill’s saucy cartoons as art. Winner’s pricier McGills went on sale for £2,500, which represents a plentiful return on 20 quid. “When I bought my Rackhams and Dulacs and Donald McGills they weren’t considered art. ‘You say you’ve bought a Donald McGill? Well, he’s rubbish. What did you pay?’ ‘Twenty pounds.’ ‘You’re mad.’”

Now that just about anything goes, McGill can legitimately be seen as a documentarist who took the pulse of a nation gagging to shed its own innocence.

Now that just about anything goes, McGill can legitimately be seen as a documentarist who took the pulse of a nation gagging to shed its own innocence.

Winner first came across McGill as a child in Brighton and Bournemouth during the war. “You’d look at them and have a titter. If you are a child, anyone with big bosoms with an innuendo is naughty. And particularly as there wasn’t much of it then.” In 1941, George Orwell wrote a deadly serious analysis of McGill’s hugely popular seaside art. As he cast a desiccated eye over images of nubile girls, randy males, big-buttocked housewives in bathers, befuddled vicars and Scots in kilts, he concluded that they were all about British repression.

“Well, we were an unbelievably repressed society,” says Winner. “Here was this neat little man, conjuring up these quite bawdy images, and people bought them in the millions. How many artists would sell 350 million prints of their work? I doubt if anyone’s done it.”

It seems amazing that McGill got away with depicting men and women clutching phallicaly huge pink sticks of rock, and the fact is that he didn’t. After the war, when the government was having a fit of the vapours about society’s slackening morals, McGill fell foul of the Obscene Publications Act and was successfully prosecuted in 1954. He was nearly 80 by then. Three years later he gave evidence to the House Select Committee set up to amend the 100-year-old law. He died in 1962. His grave in south-east London was unmarked. “It’s ridiculous!” says Winner. “So I said I will put a gravestone in for him. I’ll pay for it.”

Winner began collecting art in the early 1960s. “I used to go to the auction rooms and look over the dealers’ shoulders. And the dealer had marked his catalogue, saying £200 for a Dutch painting. I would think, well if he’s put 200 I will go 220. So the dealers hated me. You didn’t need much money in those days. I bought a Canaletto for £400 in 1963. It was a fake. They are crooks now, the auctioneers – but there they actually put on the catalogue, ‘Canaletto, a view of the Rialto Bridge, Venice.’”

He is a litigious collector. He successfully got his money back when Christie’s flogged him a bronze that wasn’t, as they claimed, by Reginald Frampton. “I put them on notice. I said, ‘You’re in big trouble, fellas.’ In the end, after threatening to go to court, I got the money back and bought this from Christie’s which is real.” He fondles a bronze Peter Pan that definitely is by Frampton.

Winner flicks the lights on and off as we pass through an impressive array of rooms. There are 46 of them. He likes his art to cheer him up. “That’s a bit gloomy,” he says a couple of times. Hence all the children’s illustrations. “I’m totally childish. I just think they take you back to a simpler and nicer world. That’s the Benjamin Bunny.” There indeed on a patch of wall between two door jambs is a tiny water colour by Beatrix Potter for which, without having actually seen it, he recently shelled out £32,000 - as much as he has on anything.

As you’d expect of a man who trawled the auction rooms for postcard art by Donald McGill, Winner is hardly an academic collector. A 17th-century portrait of the Countess of Abingdon frowns down on Winner from behind his desk. I ask who she was. “Fuck knows,” he says, switching off the light. “Some snotty cow who could afford Peter Lely. If that’s a real Lely.”

- Rude Britannia: British Comic Art at Tate Britain until 5 September

- Donald McGill Museum website

- View Michael Winner's full collection of Donald McGill originals

- Read theartsdesk review of Rude Britannia: British Comic Art

- Visit theartsdesk gallery of work from the exhibition

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment