After the Dance, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

After the Dance, National Theatre

After the Dance, National Theatre

It's hard work bringing Rattigan's bunch of lost souls to life

A pall of ennui hangs over the 1930s drawing room of the National’s latest Rattigan revival, as deadly as the boredom its burnt-out party people all dread.

Three of the five leads in Thea Sharrock's production deal as well as they can with Rattigan's sometimes implausible psychology. He was 28 when After the Dance opened in June 1939, a short-lived success to follow the froth of French Without Tears, so unless he was unnaturally precocious in his world-weariness, I doubt whether he could really have understood the mid-life crisis of characters 10 years older than himself.

It all glided into action timelessly enough, once we got past the unnecessary mood music and the audience's readiness to laugh uproariously at every line. The wealthy Scott-Fowlers have been giving parties for the last 12 years in their large but oddly comfortless London flat (ruthlessly evoked by the brilliant Hildegard Bechtler, even if she's used to grander and sometimes more abstract designs). They've been holding court since the mid-Twenties, still trying to keep things the same. There's a licensed jester - Adrian Scarborough, typically not putting a tragi-comic foot wrong from the minute we discover him under a newspaper on the ample sofa - and an impoverished cousin (John Heffernan) employed to type up the husband's less-than-sparkling monograph on the King of Naples.

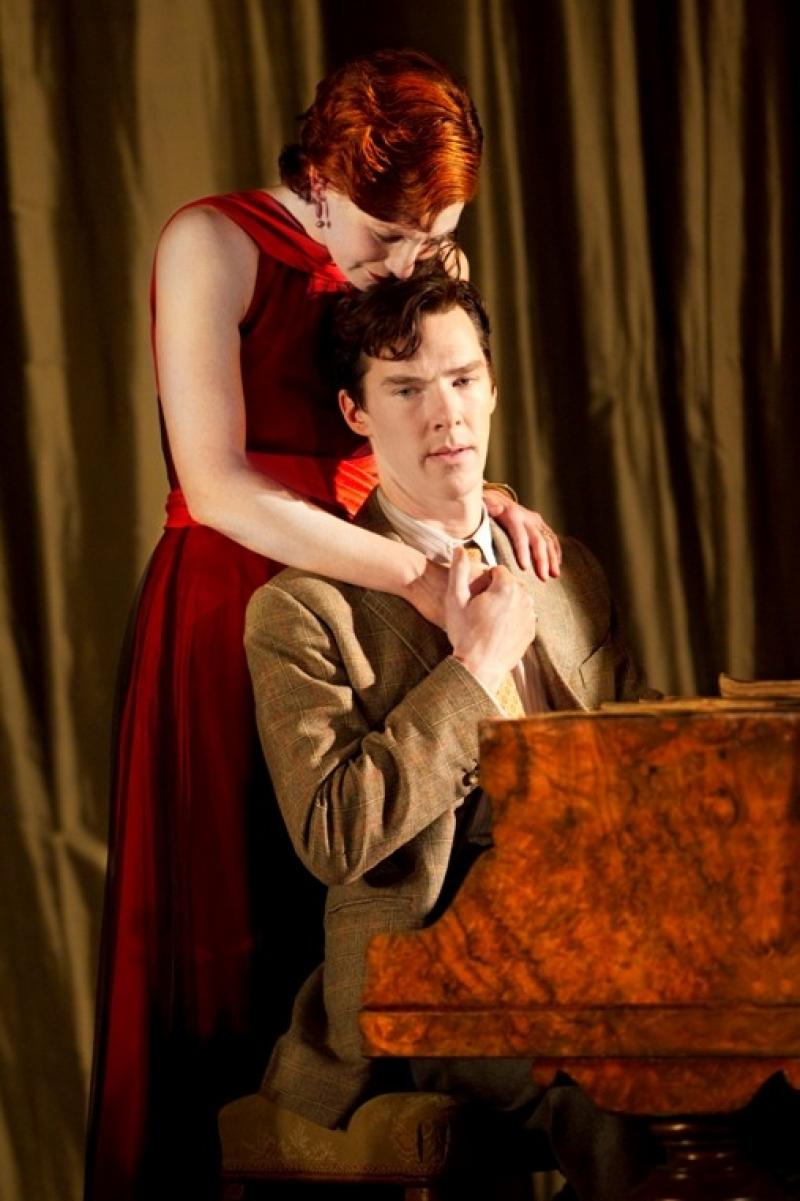

So far, so good. Nancy Carroll exudes a purposefully stagey but spellbinding vivacity as the lady of house; when Benedict Cumberbatch's David Scott-Fowler enters, he tells us all we need to know with his superbly modulated, bass-baritone-tinged tones about the failed hopes of a superfluous man. But there the links with Chekhov and other Russians stop. You see, this lost chump is about to fall for every cliché in the book and straight into the arms of a young woman determined to put a stop to his cirrhosis-inducing drinking and half-hearted attempts at academic respectability.

The would-be child bride is the stumbling block of the evening - possibly of the play itself, since it's hard to imagine her clipped determination delivered in anything other than period cadences. Faye Castelow tries hard with the Celia Johnson delivery, but never for a minute hints at the pathos that much-imitated actress brought to Brief Encounter and other dramas. Again, it's not clear to what extent we're supposed to dislike this manipulative outsider. But I wonder if we should be totally repelled by Castelow's squeaky, far-from-pneumatic siren. I didn't believe in her powers of attraction for a minute; so the all-too-easy "ask her for a divorce and let's get married" scene at the heart of Act Two is where I lost all patience with these wretched people. Our sympathies are engaged briefly by the rejected wife. Carroll captures the abyss between the mask and the reality chillingly: when she stands with her back to the audience you realise this is the first time we've seen anyone alone on stage and not giving a performance. But even this superb actress makes it hard to swallow the notion that in 12 years of marriage Joan has never told David she truly loves him simply because she's afraid he would find that "boring" (the keyword of the entire play).

Maybe people did behave like that in the 1930s. But Rattigan's encapsulation of a certain attitude needs to be made credible, and here the truthfulness flickered in only a few well-placed, devastatingly simple sentences (mostly delivered by Carroll). As for Cumberbatch's David, the production tries hard to give him a hint of a soul by having him sit at the piano and switch from raucous party music to Chopin. Later Puccini's "E lucevan le stelle" swells in his mind as preparation for the song which very loosely plagiarised it, the Jolson-Rose number "Avalon". It's a lynchpin of the drama, suggesting that music articulates what the characters can't, and it's briefly moving at a key point. But after the shocking denouement, which I ought not to reveal, everyone slips back into type. Following the only really funny scene of the evening, a chat about Manchester with Jenny Galloway's perfect, laconic Miss Potter, Scarborough's jester turns truth-teller, as jesters often do, and the focus shifts back to Cumberbatch. The next scene, with Heffernan overdoing the alienation as the rejected suitor, is as unconvincing as Peter's "solution". We can't help caring about the protagonist of a latter Rattigan drama, The Deep Blue Sea, as incarnated by Penelope Wilton and Harriet Walter. But, for all Cumberbatch's faultless delivery, did I give a damn about the fate of David Scott-Fowler? Sadly not.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Add comment