I’m within 20 yards of Wexford Opera House when I stop a couple for directions, convinced that my map is some sort of Irish practical joke. Approached down a narrow and frankly rather unpromising side street, from the exterior Wexford Opera House does a very good impression of a row of terraced houses. Demure, unassuming, barely daring to obtrude into the domestic landscape of this small town, the only outward evidence of an internationally celebrated, 750-seat theatre are some fairy lights strung haphazardly across the road outside. Yet while the venue may be coy, there’s nothing shy about the festival that takes over Wexford for two weeks every year – not so much a cultural cuckoo in this tiny Irish nest as a bird of paradise.

Giving polished and creative staging to three full-scale operas each year, with a cast of international alumni that have included Janet Baker, Patricia Rozario and Gidon Sachs, and more recently superstar tenors Juan Diego Florez and Joseph Calleja, Wexford Festival is a glorious anomaly. How does a festival devoted to the arcane and the abstruse, featuring composers and operas audiences have never heard of (Foerster’s Eva, anyone? Flotow’s Alessandro Stradella? Mayr’s Medea in Corinto?) manage to thrive in a nation that doesn’t currently support a full-time opera company?

Irish history and legend are everywhere in evidence“There’s a huge attraction in being able to see three operas you’ve never heard before in three days,” explains artistic director David Agler. “But it’s not just the opera that draws people here; there’s also something about the air and the people of Wexford. Being down in south-east Ireland on a misty, soft autumn day can be quite magical.”

“Can” is, of course, always a loaded term when it comes to Irish weather. Severe flooding in the Dublin area fills news reports in the week preceding the festival, and as we touch down at the airport we see streaks of distant rain like guy-ropes anchoring a tent of cloud over us. But during the drive down Ireland’s placidly lovely east coast, through County Wicklow and County Wexford, skies unfrown, leaving the small harbour town of Wexford silhouetted against the bright, metallic backdrop of the River Slaney estuary. It is this river, incidentally, that is responsible for the town’s Irish name – Loch Garman: christened, with appropriately operatic drama, after a young man drowned at the estuary mouth when a vengeful enchantress released the flood waters.

“Can” is, of course, always a loaded term when it comes to Irish weather. Severe flooding in the Dublin area fills news reports in the week preceding the festival, and as we touch down at the airport we see streaks of distant rain like guy-ropes anchoring a tent of cloud over us. But during the drive down Ireland’s placidly lovely east coast, through County Wicklow and County Wexford, skies unfrown, leaving the small harbour town of Wexford silhouetted against the bright, metallic backdrop of the River Slaney estuary. It is this river, incidentally, that is responsible for the town’s Irish name – Loch Garman: christened, with appropriately operatic drama, after a young man drowned at the estuary mouth when a vengeful enchantress released the flood waters.

Irish history and legend – and yes, perhaps just a bit of Agler’s autumnal magic – are everywhere in evidence. I wander down the truthfully, if optimistically, named Main Street (meandering as an Irishman’s conversation, and just as beguiling) to a little beyond the centre of town. On the site of a pre-Christian temple to Odin, sit the remains of the 12th-century Selskar Abbey. Largely destroyed by Cromwell, its architectural bones tell the tale of a Norman knight who returned from the Crusades to find that his fiancée, convinced of his death, had become a nun. In his grief the knight himself became a monk, founding and devoting his life to the religious community of Selskar.

Irish history and legend – and yes, perhaps just a bit of Agler’s autumnal magic – are everywhere in evidence. I wander down the truthfully, if optimistically, named Main Street (meandering as an Irishman’s conversation, and just as beguiling) to a little beyond the centre of town. On the site of a pre-Christian temple to Odin, sit the remains of the 12th-century Selskar Abbey. Largely destroyed by Cromwell, its architectural bones tell the tale of a Norman knight who returned from the Crusades to find that his fiancée, convinced of his death, had become a nun. In his grief the knight himself became a monk, founding and devoting his life to the religious community of Selskar.

Even Wexford’s state-of-the-art opera house, designed and built between 2005 and 2008, is dressed in the clothes of the past, occupying as it does the site of the town’s 19th-century Theatre Royal. Home to Wexford Opera since its founding in 1951, as the festival grew so the theatre’s limitations of capacity and facilities became ever more of a hindrance. When it became clear an alternative was needed, options included a striking new location on the Ferrybank side of the river. But staunch in their allegiance to the festival’s quirky, hidden opera house, the Festival Board instead opted to build on the original site. The result is impressive both in its acoustic intimacy and deceptively large capacity. For visitors not keen on opera, the building also houses a top-floor café with the best views (and coffee) in Wexford, looking out over the town’s rooftops to the river. Not a place for solitary contemplation (not even a notebook and a novel deter friendly festival-goers from conversation), it’s a warmly unofficial hub of festival activity before night falls and the town’s many pubs take over.

But what of the music itself in this, the festival’s 60th anniversary year? Taking marital love as its theme, Wexford’s traditional categories (a singers’ opera, a comedy and a so-called “thinking piece”) were this year filled by Ambroise Thomas’s La cour de Célimène, Roman Statkowski’s Maria, and Gianni di Parigi, adding to the festival’s growing catalogue of lesser-known Donizetti. Framing Statkowski’s bleak love story (rendered even chillier in Michael Gieleta’s Solidarity-era production) in two such smiling, gilded works was a clever decision, creating a dramatic arc over the three days that celebrated the operas’ individual strengths rather than exposing their limitations.

But what of the music itself in this, the festival’s 60th anniversary year? Taking marital love as its theme, Wexford’s traditional categories (a singers’ opera, a comedy and a so-called “thinking piece”) were this year filled by Ambroise Thomas’s La cour de Célimène, Roman Statkowski’s Maria, and Gianni di Parigi, adding to the festival’s growing catalogue of lesser-known Donizetti. Framing Statkowski’s bleak love story (rendered even chillier in Michael Gieleta’s Solidarity-era production) in two such smiling, gilded works was a clever decision, creating a dramatic arc over the three days that celebrated the operas’ individual strengths rather than exposing their limitations.

Barlow’s lightness of touch gives this gift-wrapped, Ladurée macaroon of an opera everything it needs to delight

It is this understanding of the material, this commitment to operatic lame ducks, whether “neglected, lost or just downright ignored”, that still sets Wexford apart. There can be no doubt that opera programming is changing, and the festival’s archival approach has caught on across the UK and internationally over the past 20 years, with most companies now featuring a token rarity among their Traviatas and Figaros. It’s a phenomenon Agler describes as both “a compliment and a challenge” for Wexford, yet one that too often frames these discoveries cruelly, setting them up to fail alongside the titans of Mozart or Verdi. Here they are given the opportunity to stand – and sometimes fall – alone.

Occasionally a director, a concept and a score will come together in an operatic synthesis so natural as to feel inevitable: David McVicar’s Giulio Cesare, Jonathan Miller’s Rigoletto, David Bosch’s revelatory Mitridate Re in Ponto. Stephen Barlow’s La cour de Célimène might not wield the weight of some of these classics, but then neither does the work itself. Barlow’s lightness of touch, his meticulous balance of affectation and sincerity, exaggeration and simplicity, and above all his eye for visual detail, give this gift-wrapped, Ladurée macaroon of an opera everything it needs to delight.

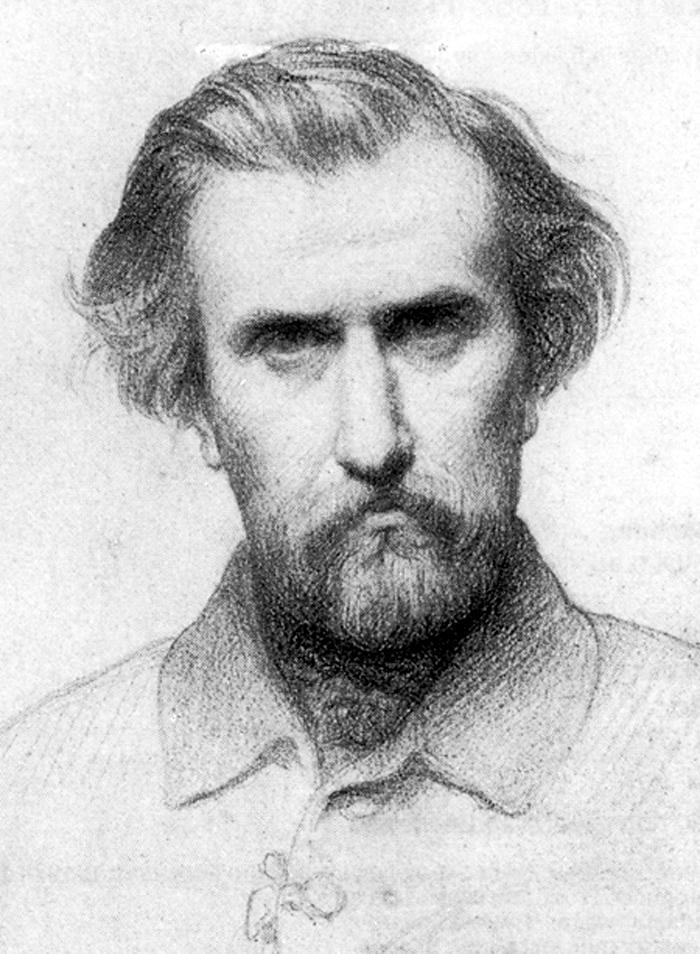

Nineteenth-century French composer Ambroise Thomas (pictured right) is best (perhaps solely) known for his operatic hit Mignon (staged at Wexford back in 1986), but was the prolific author of some 24 operas. Still clinging to bel canto intricacies in the age of the Romantic opera, Célimène received just one run in 1855. Old-fashioned it may have been to the self-conscious patrons of the Opéra-Comique, but its balance of florid Rossini-esque vocal writing (so challenging for La Comtesse Célimène herself that no singer would dare take on the role from Marie Claire Miolan for whom it was written) and French melody is a deeply attractive one, especially when allied to a piquant, feminist plot.

Nineteenth-century French composer Ambroise Thomas (pictured right) is best (perhaps solely) known for his operatic hit Mignon (staged at Wexford back in 1986), but was the prolific author of some 24 operas. Still clinging to bel canto intricacies in the age of the Romantic opera, Célimène received just one run in 1855. Old-fashioned it may have been to the self-conscious patrons of the Opéra-Comique, but its balance of florid Rossini-esque vocal writing (so challenging for La Comtesse Célimène herself that no singer would dare take on the role from Marie Claire Miolan for whom it was written) and French melody is a deeply attractive one, especially when allied to a piquant, feminist plot.

Heightening the opera’s original Ancien Régime setting with some judicious anachronism, Paul Edwards’s off-kilter gilt frame sets the tone for the off-centre period camp that ensues. Célimène herself (Claudia Boyle, pictured above surrounded by her suitors) descends from above, the rather more knowing double of Fragonard’s pink-clad girl in The Swing, sings coloratura showstoppers while gorging on confectionary, and generally gives Marie Antoinette a run for her money. This young Irish singer (whose voice has caught the attention of Riccardo Muti) seems likely to become one of Wexford’s great sopranos, and along with Maria conductor Tomasz Tokarczyk is Agler’s pick of his 2011 company.

Irish talent is a recurring theme of the festival, and elsewhere is perhaps most evident in the Wexford Festival Orchestra; 85 per cent of its members are drawn from this nation – something Agler admits would probably not have been possible 10 years ago. Working for seven weeks as a company alongside the principals and the chorus of young professionals (a welcome 2011 innovation, and one set to endure), there is a precision and an energy about the ensemble that you too rarely get from the rough and tumble rehearsal schedules of the major UK opera houses. These musicians work together not only in the three major productions but in lunchtime recitals and the short-works series that Agler has been so instrumental in championing, and the resulting trust and familiarity between them is clear in performance.

It was the chorus that carried Statkowski’s Maria (1906) – certainly the most interesting of the season’s works, but also the most flawed. A striking Tchaikovsky-influenced opening act sets up a father-son tragedy of serious heft. Carried by its elegant orchestration (a cello solo accompanying the District Governor’s (Adam Kruszewski) kidnap order for his son’s fiancée Maria (Daria Masiero) is particularly chilling for its lyric denial of guilt), the work falters when plans turn to action after the interval.

It was the chorus that carried Statkowski’s Maria (1906) – certainly the most interesting of the season’s works, but also the most flawed. A striking Tchaikovsky-influenced opening act sets up a father-son tragedy of serious heft. Carried by its elegant orchestration (a cello solo accompanying the District Governor’s (Adam Kruszewski) kidnap order for his son’s fiancée Maria (Daria Masiero) is particularly chilling for its lyric denial of guilt), the work falters when plans turn to action after the interval.

The tension built so carefully through the slow-burn psychodrama of the opening dissipates in a rather verbose second half, all deferrals and indecision. Masiero gives all she can to Statkowski’s rather anonymous vocal lines (the real meat is in the orchestra), but a weary-sounding Rafal Bartminski (pictured above with the Wexford Festival Chorus) couldn’t quite carry the idealistic authority of husband Waclaw through this last performance. Director Michael Gieleta’s relocation of the story to the Gdańsk shipyards is predictable enough, but comes into its own during the many orchestral interludes, where a blend of live tableaux and projected photographs make an interesting comment on the porous nature of national memory.

Donizetti has become a staple of the Wexford diet, and seemed to go down well as ever with the audience in the form of this year’s rarity Gianni di Parigi. A plot that would shatter in a light breeze sees the Princess of Navarre and the Dauphin of France (in disguise, of course) united in a small provincial hotel. Cleanly articulated comedy from director Giacomo Sagripanti extracts all possible energy from the scenario, with a star trouser-turn from mezzo Lucia Cirillo (pictured right with Edgardo Rocha as Gianni) as the Dauphin’s page Olivero and some authoritative coloratura action from Zuzana Markova’s Principessa leading the cast.

Donizetti has become a staple of the Wexford diet, and seemed to go down well as ever with the audience in the form of this year’s rarity Gianni di Parigi. A plot that would shatter in a light breeze sees the Princess of Navarre and the Dauphin of France (in disguise, of course) united in a small provincial hotel. Cleanly articulated comedy from director Giacomo Sagripanti extracts all possible energy from the scenario, with a star trouser-turn from mezzo Lucia Cirillo (pictured right with Edgardo Rocha as Gianni) as the Dauphin’s page Olivero and some authoritative coloratura action from Zuzana Markova’s Principessa leading the cast.

The festival’s founder, Dr Tom Walsh, was clear from the outset that he wanted Wexford to be the final festival in the European cultural year. Audiences that start in Glyndebourne and move on through the course of the summer to Salzburg, Verbier, Edinburgh and Bayreuth end up as autumn gives way to winter in a small harbour town on the east coast of Ireland. Despite calls to change the dates, the festival has clung wisely to its original slot, giving Wexford its unique end-of-term feel. Audiences may don black tie each night, but that doesn’t stop this being an unbuttoned sort of event.

The informality of the lunchtime concerts that shake the windows of St Iberius’s Church, the conversational comings and goings through pre-concert talks (and even, it must be said, occasionally through overtures), the doctors, lawyers and teachers who all set aside their professions for two weeks a year to staff the festival, all add up to Wexford’s school's-out sense of fun and freedom. Perhaps that’s the reason why, as we cross hands and join in the traditional chorus of "Auld Lang Syne" on the final festival night, so many of the audience already know they’ll be back again next year, just as they were last year, and the year before that.

- Find out more about Wexford Festival Opera

Add comment