Photo Gallery: A Century Apart, James Ravilious & John Wheeley Gutch | reviews, news & interviews

Photo Gallery: A Century Apart, James Ravilious & John Wheeley Gutch

Photo Gallery: A Century Apart, James Ravilious & John Wheeley Gutch

Cameras change, centuries pass, but photographers stay the same

Life changes at such speed in cities that it seems as if all the world must move at the same pace. Photographs prove otherwise. Looking at the two portfolios of West Country photographs below, you could surely not readily believe that more than a century separates them.

James Ravilious

The son of the renowned engraver and watercolourist Eric Ravilious, James (1939-1999) spent most of his adult life in a small North Devon village dedicated to producing the perfectly composed, painstakingly produced black and white photographs of local scenes, an archive of late 20th-century life in that region that seems an age away from metropolitan existence.

The son of the renowned engraver and watercolourist Eric Ravilious, James (1939-1999) spent most of his adult life in a small North Devon village dedicated to producing the perfectly composed, painstakingly produced black and white photographs of local scenes, an archive of late 20th-century life in that region that seems an age away from metropolitan existence.

Set in villages, lanes and fields, and including portraits of local farmers’ families and the animals involved in everyday activities in the 1970s and 1980s, the photographs, like his father’s works, continue art history’s pastoral tradition, and exude an unmistakeable Englishness without surrendering to sentimentality. Names like Wilfred Pengelly, Archie Parkhouse, Alfie Pugsley, Jean Pickard recur again and again, and their villages Chumleigh, Beaford, Dolton, Sheepwash, families embedded in their land for many generations, their homes worn by time and usage. It is a record so personal that it becomes universal, and is rightly held as an archive in the Beaford Arts centre, Devon.

James’s earliest influences included Cartier-Bresson, but he was also inspired, like his father, by the Kentish master engraver Samuel Palmer. He cited his The Morning of Life as a favourite: a tranquil woodland scene illuminated by morning sun and that clearly influenced James’ use of natural light, regardless of seasons or locations in Devon or rural Italy, Greece and France. Cows ambling down a lane are sprinkled with sunlight breaking through the trees, and the neat flock of sheep following a farmer’s wife, appears golden even in black and white.

James inherited his father’s acute sense of design, which raises the appeal of his photographs beyond their sensitive human interest level. The farmer loading milk-churns onto a lorry, the hedger taking a break, the farmer stacking stooks, all unwittingly create a beautifully sculptural shape on the land.

James inherited his father’s acute sense of design, which raises the appeal of his photographs beyond their sensitive human interest level. The farmer loading milk-churns onto a lorry, the hedger taking a break, the farmer stacking stooks, all unwittingly create a beautifully sculptural shape on the land.

Ravilious moves as slowly through the countryside with his camera as the cows and sheep down the lanes, and when he turns the camera onto the local people, in the farmyards or streets or in their cottages in his gentle ease, they hardly notice him. The doctor sits at a farmer’s sick-bed in his dimly lit cottage, a woman cuts the Christmas turkey, her father laughing so loudly, it’s almost audible, farmers out in the fields in all weathers, the cockerel stalking unflappably over flowerpots. Recording time now past and working lives now superseded by machinery, these photographs have even greater significance than their aesthetic appeal. The current Eastbourne exhibition linked illuminatingly displays the son's images alongside his father's landscape paintings. (SUE STEWARD)

John Gutch

A man in thrall to a passion not only for the medium, but crucially with a keenly imaginative and observant eye

The rugged, macabre, almost pagan landscapes that dominate mid-Victorian literature and poetry come to vividly immediate life in the photographs of the very early English photographer John Wheeley Gough Gutch (1808-62). In the early 1800s cameras were scientific viewing devices and Gutch was born into a cultured Bristol family with many artistic and scientific friends. The poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey and William Wordsworth were acquaintances, and Gutch, although he trained originally as a surgeon, was throughout his life much influenced by the written word.

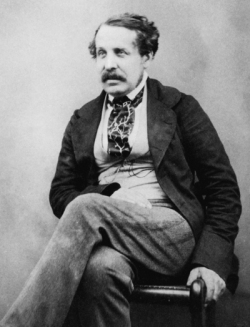

Like Fox Talbot, who invented the first camera as an aid to sketching, Gutch (pictured right in 1855 by John Crace, © J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) was a frustrated artist who bought a camera lucida, a portable viewing device, to help him make more accurate drawings of Italian landscapes. However he was also a keen amateur naturalist and geologist, and working as a physician in Swansea in the 1840s he was among a circle of intellectuals who were lively followers of gadgets to assist in their scientific pursuits.

Like Fox Talbot, who invented the first camera as an aid to sketching, Gutch (pictured right in 1855 by John Crace, © J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles) was a frustrated artist who bought a camera lucida, a portable viewing device, to help him make more accurate drawings of Italian landscapes. However he was also a keen amateur naturalist and geologist, and working as a physician in Swansea in the 1840s he was among a circle of intellectuals who were lively followers of gadgets to assist in their scientific pursuits.

When photography was invented in the 1840s - that is, the permanent recording of images - Gutch was swept up by the exciting new find, and had the knowledge and curiosity for the labour-intensive mixing of chemicals and preparations of glass plates, print papers and salt solutions, fingers blackened by silver nitrate. However, travelling with a camera was nigh impossible (you needed a darkroom to hand) until Frederick Scott Archer invented a new camera and darkroom combined (pictured below left).

Gutch eagerly got one of these cutting-edge devices and, taking advantage of his new job as a Foreign Service Queen's Messenger (a diplomatic courier), took his camera on all his trips both in the UK and in Europe. The photographs he made for the next three years show a man in thrall to a passion which was not only for the medium, but crucially with an imaginative and observant eye for all the life around him - a human naturalist, in effect.

In Search of the Picturesque, Ian Charles Sumner’s new monograph of this virtually unknown photographer, gathers together images of an England a century and a half ago, as Gutch, toting his heavy camera on his back, and despite the misery of gout, travelled further west into Cornwall as well as Somerset and Worcester, and then up to the Lake District (where he photographed the tombs of his parents’ friends, Wordsworth, Southey and Coleridge). This was the era of Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and R D Blackmore, and while in his own time it was his images of spectacular geological features or archaeological antiquities that attracted most interest, the individuality of the people he photographed survives to this day, not just surprising but touching too.

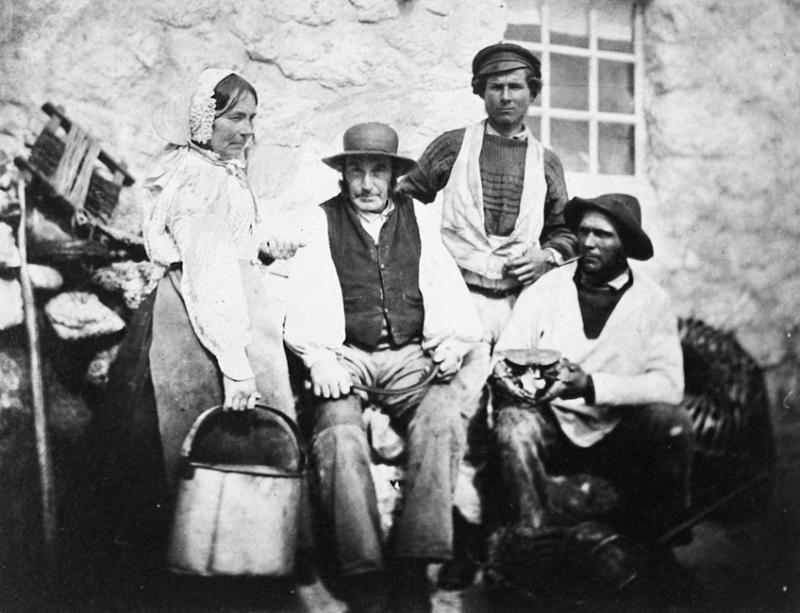

The Cheddar Gorge picture in early April 1856 (1) is significant, as it proved to Gutch that he could carry his cumbersome Scott Archer camera even up steep slopes to obtain dramatic views, as he did on the Cornish cliffs (2) where he photographed stunted young miners (3), and the fishing ports (4, 5, 6) where life was so different from the civilised Malverns.

Nearer home Gutch's records of his own daily life show the reactions of people around him to being photographed - the Bathman (7) who served to relieve Gutch’s ailments, a self-portrait in the Abbey churchyard (8), or the discreetly excited stares of villagers on the earthern broadway of Westbury-on-Severn (9).

Although the selection here offers Gutch’s views of the West Country complementary to James Ravilious’s 130 years later, it’s impossible not to include his weirdest and, indeed, most picturesque image - that of the Lake District farmer of Brackenrigg (10) who mounted the entire skeleton of a horse on the side of his house, truly a macabre sight that must have terrified local children. (ISMENE BROWN)

Click on a photograph to enter the slideshow (images © Richard Meara, Michael G Wilson, Ian Sumner):

[bg|/PHOTOGRAPHY/ismene_brown/J_W_G_Gutch]

- Familiar Visions: Eric and James Ravilious, Father and Son, is at Towner Gallery, Eastbourne till 12 September

- In Search of the Picturesque: the English Photographs of J W G Gutch 1856-59, by Ian Charles Sumner (Westcliffe Books)

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment