Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet

Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet

Jennifer Homans' magnificent study of the birth and death (or not) of an art form

It is rare that you read a book, and mentally shout “Yes! Yes!” as you tick off all the things you agree with, but had never actually verbalised. It is even rarer to read a book where, in a subject you know pretty well, on almost every page you learn at least one fascinating new thing. But Jennifer Homans’ Apollo’s Angels is that book.

Much has been made of Homan’s epilogue, in which she mourns the death of ballet, the art she so loves. I can understand her feelings – I even feel the same emotion that she does, at least in part. It’s merely that I think she’s wrong (the only place I do). Dance is not dying, and is certainly not dead. But it has definitely evolved radically in the last few decades, developing in a way that makes “ballet” a rather archaic word for what is more encompassingly “dance”.

But this epilogue, while headline-grabbing, is only the froth on the surface. Apollo’s Angels is a book that every dance lover should read, for it explains not only the art we love, and why we love it, but it explains why it matters. And in a world where dance is seen as a minority taste, frequently disparaged as elitist, why it matters is of paramount importance.

The early section, on the development of dance from the 16th to the 18th centuries, is a model of academic rigour; clear, lucid and astonishingly detailed for what is, in effect, ballet’s pre-history. But once the 19th century is underway, the book really lifts off. Homans’ analysis of the birth of Romanticism, her exploration of the seminal Robert le Diable and of Marie Taglioni’s part in both is a formidable synthesis of social history (the piece was premiered after the uprising of the Lyon silk weavers) and political history (the reverberations of the revolution and the current political instability across Europe), as well as art, music and literary history (in later sections, she takes on economics and the economics of dance as well).

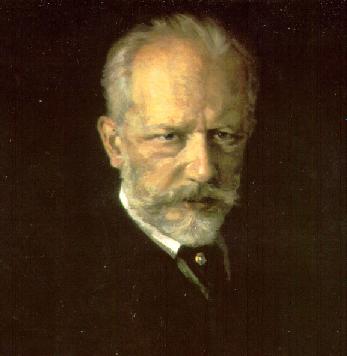

As she notes, “Taglioni was both saintly and a force of anarchy and dissolution, Robespierre and the ancient regime wrapped into a single disturbing vision.” Similarly, her chapter on Bournonville and the development of the distinctive Danish style of ballet is a mine of fascinating detail, as well as (a Homans speciality) a gripping analysis of what makes his choreography so remarkably different from everyone else's. And she is also just fun to read: I am thrilled to know that the ballet Excelsior, in 1881, covered the invention of the steamboat, the telegraph and electricity, included a dance for Arab jugglers and American telegraph operators (possibly not together), and had in its cast 12 horses, two cows and an elephant. The chapter on Imperial Russia and the great classical ballets – Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty – is magisterial, but despite its almost epic breadth, still wonderfully detailed. Homans shows how Petipa took the French Romantic tradition and translated it into “a far grander and more formal Russian idiom”, creating a more amplified architecture, both in individual steps and in overall conception. Sleeping Beauty, Homans shows, is therefore not so much a narrative ballet as “a sympathetic ritual re-enactment of the courtly principles” of both dance and the Russian court, which via the genius of Tchaikovsky (pictured above right) and Petipa are transformed into poetic metaphor. Similarly she homes in on the core of Swan Lake: for Petipa, the world of courtly taste, grace and manners was represented by classical technique, while Ivanov’s desire was constantly to undercut the surface, to discard pattern for lyrical intimacy, interiority. He didn’t want to show a perfect court world, but a perfect other world, a world out of time and place. It is the synthesis of the sharp dichotomy of these two visions that makes the work a masterpiece.

The chapter on Imperial Russia and the great classical ballets – Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty – is magisterial, but despite its almost epic breadth, still wonderfully detailed. Homans shows how Petipa took the French Romantic tradition and translated it into “a far grander and more formal Russian idiom”, creating a more amplified architecture, both in individual steps and in overall conception. Sleeping Beauty, Homans shows, is therefore not so much a narrative ballet as “a sympathetic ritual re-enactment of the courtly principles” of both dance and the Russian court, which via the genius of Tchaikovsky (pictured above right) and Petipa are transformed into poetic metaphor. Similarly she homes in on the core of Swan Lake: for Petipa, the world of courtly taste, grace and manners was represented by classical technique, while Ivanov’s desire was constantly to undercut the surface, to discard pattern for lyrical intimacy, interiority. He didn’t want to show a perfect court world, but a perfect other world, a world out of time and place. It is the synthesis of the sharp dichotomy of these two visions that makes the work a masterpiece.

It is in the 20th century that she and I begin to part company. Here Homans, trained as a dancer at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, becomes somewhat hagiographic about her teacher. Like her, I think he was probably the greatest genius ballet had seen since Petipa and Ivanov. But when she begins to judge all his contemporaries in relation to him, her argument becomes excessively narrow. Ashton is good when he is most like Balanchine, less good as he moves further away from Neo-Classicism. And perhaps, as a signal of her detachment from this period, in these later chapters Homans barely discusses the political or social history of the times. She briefly notes that Ashton’s The Dream was choreographed in the year of The Beatles, and Oh! Calcutta! premiered the same time as his Enigma Variations, but she does not create the web of cross-connections that make her 19th-century chapters so enlightening.

My tastes, like Homans', run along the Classical/Neo-Classical spectrum. So do my values, and the very fact that I use words like “values” to discuss this art I love so much puts me on her wavelength. François de Lauze, a 17th-century dance master, said that ballet was "the science of behaviour towards others”, and it is that sense of the art form’s morality that so speaks to me. Ballet, writes Homans, is about hard work, humility, limits, self-knowledge and presentation, self-control, proportion, grace. Perhaps it is the very old-fashionedness of this list of virtues that makes it seem as if it is dying.

Maybe the best thing to do is remember that people have been writing ballet’s epitaph almost since its birth. In the 19th century the Danish choreographer Bournonville said, “The glorious days of the dance are past.” They weren’t then. Most likely they aren’t now. And while we’re waiting to find out, we have Jennifer Homans’ magnificent Apollo’s Angels to remind us of why we are right to be so moved by the silent women in white.

- Find Jennifer Homans' Apollo's Angels on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Add comment