Roméo et Juliette: Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Elder, Royal Festival Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Roméo et Juliette: Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Elder, Royal Festival Hall

Roméo et Juliette: Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Elder, Royal Festival Hall

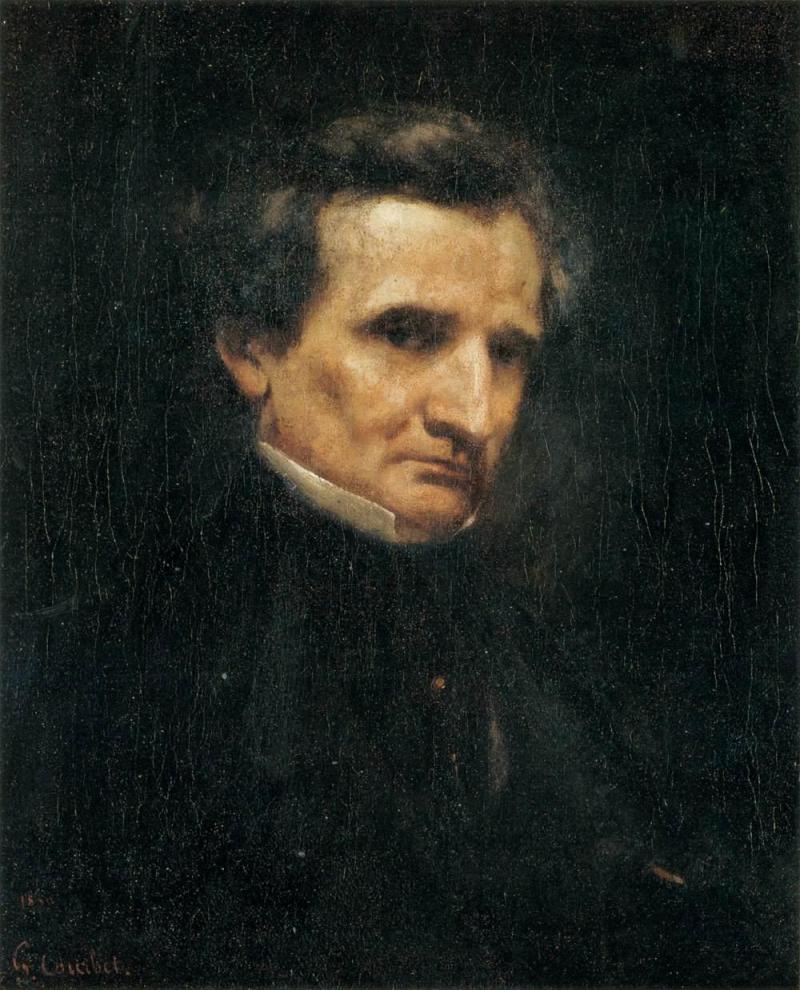

Berlioz's love-letter to the orchestra is given a bold and beautiful performance

It's one of the fundamental rules of concert-going that in any given season there will be one piece that trips you up. And that piece will always be by Berlioz.

The first riddle was what exactly was it that we were hearing? The composer called Roméo et Juliette a "Dramatic Symphony". But what symphony do you know that begins with an overture, goes into a chorus, enters a solo contralto aria and then a spritely tenor cabaletta? One could mistake the opening for an opera. Yet what opera contains two enormous symphonic poems at their core and finds no corporeal or vocal room for the two main protagonists? Some see parallels with the choral symphonies of Mahler and Beethoven. But the works of these two strike me as quite formulaic when compared to Berlioz's unidentified symphonic object.

Elder felt no shame - rightly - at bringing out every bold bit of Berliozian colour

The oddity of the piece was mapped out last night physically on the Royal Festival Hall stage, as mezzos, tenors, basses and whole choirs filed on and off, on and off. Four harps replaced three trombones. One percussionist became two. Two became four. Four became eight. It was orchestral cell division. A cor anglais led the woodwinds. The strings duetted with two Turkish zills. Melodies wafted up from the double basses. Berlioz rarely shied away from this child-in-a-sweetshop behaviour when it came to orchestration. But this commission (Paganini asked for the work in return for 20,000 francs, no strings attached) allowed more freedom than most.

In a way then, this is a love letter to the orchestra. That Berlioz's exploited every bit of flesh and fat of the early 19th-century orchestral beast doesn't make things easy on the orchestra or conductor. But both Sir Mark Elder and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment despatched every technical challenge with ease. There was an infectious hyperactivity to the Grande Fete chez Capulet and an addictive lightness to the scampering of the Queen Mab Scherzo. Even in this unusually expanded form, the OAE clung together like chamber musicians throughout. Elder's dramatic sense was there at every key climactic point and dramatic musical turn. He felt no shame - rightly - at bringing out, even at times exaggerating, every bold bit of Berliozian colour: the guitarish harps, the thundering timps, the trombones and tambourines.

In all this generosity, it's odd how small a role the story of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet - even its main themes - plays. There is virtually nothing here except the bare bones. None of the main characters appear. Oratorio-like reflections pour forth from choirs, who later also adopt the thoughts of the Montagues and Capulets. The Schola Cantorum and BBC Symphony Chorus were heartfelt in their offerings, even though they had to work with the least interesting musical material of the evening. There are two small but beautiful roles for the everyman and everywoman. Patricia Bardon was as full-voiced and stentorian as John Mark Ainsley was delicate and Queen Mab-ian. Then out of the blue comes Friar Laurence. Orlin Anastassov performed the role with plenty of spirit.

These vocal moments are side dishes, however, to the main act of musical love making in the Part Three Scene d'Amour. It's a movement built on one of very greatest melodies ever written. A tune so ravishing you wish you could eat it on toast or rub it into your skin. With Elder we got the next best thing. He shaped it and its numerous permutations with such care and let it sing with such heat it felt like it was seeping into every pore.

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Add comment