Gabriel Orozco, Tate Modern | reviews, news & interviews

Gabriel Orozco, Tate Modern

Gabriel Orozco, Tate Modern

A thrilling new show of an art-world great

The show opens with his iconic 1991 piece, My Hands are My Heart, a double photograph of Orozco’s naked torso. In the first photograph his hands clutch a hidden object at chest-height; in the second the hands splay open to present to the viewer a piece of clay, now impressed with his fingermarks in the shape of a heart. In two simple images, Orozco encapsulates the artist’s act of creation, and then of offering the creation to the viewer.

Much of his work relies on this type of essentialism: he uses found materials, recycled objects, to make interventions in the world, to create an art of improvisation. But unlike so many contemporary artists, Orozco is not narrowly defined by either style or medium. Indeed, it may be that his relatively low profile to the general public has been created by his cornucopian variety: drawings, paintings, sculpture, found objects, reclaimed materials transformed – you name it, Orozco has manipulated it, or picked it up, or shown it.  Many of his photographs, seemingly random street scenes shot without thought, are in fact on second glance highly sophisticated interventions: sometimes they are created images – a pile of watermelons each crowned enigmatically with its own tin of cat food; at other times, they are images of ephemerality – Breath on Piano is just that, a photograph of the artist’s breath on the polished black of a concert grand, shot in the fleeting seconds before it evaporated. Still others are simply of a formal beauty that clutches at the heart – Pinched Ball (pictured right) shows a deflated football, with rainwater caught in its sagging interior.

Many of his photographs, seemingly random street scenes shot without thought, are in fact on second glance highly sophisticated interventions: sometimes they are created images – a pile of watermelons each crowned enigmatically with its own tin of cat food; at other times, they are images of ephemerality – Breath on Piano is just that, a photograph of the artist’s breath on the polished black of a concert grand, shot in the fleeting seconds before it evaporated. Still others are simply of a formal beauty that clutches at the heart – Pinched Ball (pictured right) shows a deflated football, with rainwater caught in its sagging interior.

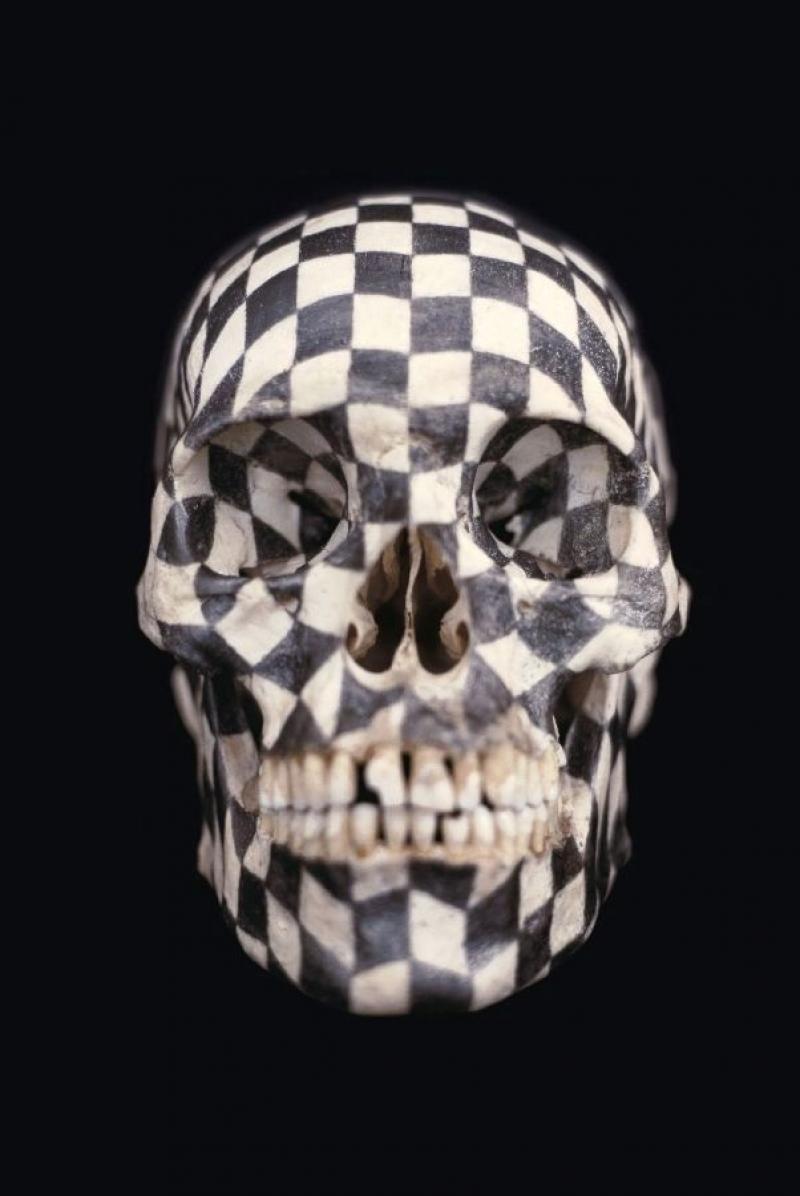

Yet all show a world that is one of complexity and changeability. The artist’s interventions do not undermine the randomness of the world, but enhance and expound on it. One of Orozco’s most famous pieces is Black Kites (main picture, above), a skull on which he has drawn a grid of squares. The skull, an organic reality, engages with and parries the attempt of the artist to impose a system, a sense of regularity and order. The grid is rationality, the skull uncertainty – the two sides of life that are constantly at odds.

Similarly Finger Ruler is a sophisticated take on that perennial problem children have when ruling lines and the finger holding the ruler gets in the way, creating a blip. Orozco takes that blip and through repetition and reiteration, enables us to consider the limits and role of physical intervention, the accidental in art, and the creation of beauty, for this scrolled pencil drawing is indeed a thing of beauty, pure and spare as a Japanese landscape.

Geometric patterns, the body, the shape and size of the artist as a present absence constantly recur. Yielding Stone (pictured left) is a Plasticine ball that was made to the same weight as Orozco himself. He then rolled the ball through the streets of New York before displaying it, complete now with its ragged edges, and a collection of dirt and refuse picked up on its journey: the ball is the product of its journey through the streets, just as we are the product of our own journeys, physical and mental. Even the fact that it is the weight of the artist then, in 1992, when it was made, stresses the transformative power of journeying, and time: it is probably no longer the same weight as the artist nearly two decades later, for the object and the man have made separate voyages.

Geometric patterns, the body, the shape and size of the artist as a present absence constantly recur. Yielding Stone (pictured left) is a Plasticine ball that was made to the same weight as Orozco himself. He then rolled the ball through the streets of New York before displaying it, complete now with its ragged edges, and a collection of dirt and refuse picked up on its journey: the ball is the product of its journey through the streets, just as we are the product of our own journeys, physical and mental. Even the fact that it is the weight of the artist then, in 1992, when it was made, stresses the transformative power of journeying, and time: it is probably no longer the same weight as the artist nearly two decades later, for the object and the man have made separate voyages.

The dirt we collect, the dirt we leave behind, the traces of ourselves in what we slough off are an abiding concern. Lintels is one of Orozco’s most remarkable pieces, a collection of drying-machine lint, made up of fluff, skin, hair and dust, carefully pressed out and hung over rows of clothesline. The ghosts of dead clothes, the ghosts of the pasts of those who wore those clothes, make this a mourning, an elegy for what they, and we, were. But it is also a future: lintels, a doorway to something new.

The spirit of Marcel Duchamp hangs over so much of what Orozco is interested in: his love of games (a chess set, all knights, is on display here; as is Carambole, a billiard table, reshaped, and without any pockets), and also his quirky humour. “I come from a country where a lot of art is labelled Surrealist,” says the artist. “I grew up with it and I hate that kind of dream-like, evasive, easy, poetic, sexual, cheesy Surrealist practice. I try to be a Realist. There is humour in my work but I’m not playing cynical games or flirting with the art world or engaging with the frivolity of the market.” And it is his refreshing lack of cynicism, his lack of desire to create statement pieces, that makes this show so come-hitherish, the kind of art (and artist) one is happy to spend time with. Until You Find Another Yellow Schwalbe (pictured right) is an unusual work in Orozco’s oeuvre, in that it is a series of photographs. In Berlin one year, the artist used one of these yellow scooters to get around the city. He began to find there was a freemasonry of Schwalbe owners, and he set out to photograph his beside any others he came across. Then Orozco planned a little mini-happening: he left notes on the scooters, announcing a Schwalbe-owners’ reunion, to coincide with the sixth anniversary of the reunification of Germany, his to be held, modestly, in a parking lot. Only two other owners showed up. “I greeted them”, says the artist, “with joy, refreshments and cookies.” The photographs of pairs of bikes thus ends with the sudden image of a third, while offstage, “joy, refreshments and cookies” are being offered.

And it is his refreshing lack of cynicism, his lack of desire to create statement pieces, that makes this show so come-hitherish, the kind of art (and artist) one is happy to spend time with. Until You Find Another Yellow Schwalbe (pictured right) is an unusual work in Orozco’s oeuvre, in that it is a series of photographs. In Berlin one year, the artist used one of these yellow scooters to get around the city. He began to find there was a freemasonry of Schwalbe owners, and he set out to photograph his beside any others he came across. Then Orozco planned a little mini-happening: he left notes on the scooters, announcing a Schwalbe-owners’ reunion, to coincide with the sixth anniversary of the reunification of Germany, his to be held, modestly, in a parking lot. Only two other owners showed up. “I greeted them”, says the artist, “with joy, refreshments and cookies.” The photographs of pairs of bikes thus ends with the sudden image of a third, while offstage, “joy, refreshments and cookies” are being offered.

And really, can one ask for more?

- Gabriel Orozco at Tate Modern until 25 April

- Books on Gabriel Orozco on Amazon

- Watch MoMA's multimedia slideshow

Below, Gabriel Orozco speaks about his photography

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment