A Midsummer Night's Dream, Barbican Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Barbican Theatre

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Barbican Theatre

A World War II setting fails to serve either Shakespeare or Britten's magic vision

Love it or hate it Christopher Alden’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at English National Opera last year made quite the impact, banishing any fey woodland glades and general waftiness from Benjamin Britten’s opera and embracing a rather more astringent visual aesthetic. It’s unfortunate then that Martin Lloyd-Evans’s production for the Guildhall School of Music and Drama should follow so closely behind, begging comparisons that don’t best serve his World War II interpretation.

Britten’s eerie glissandi break the silence in a moonlit hospital ward or dormitory, rows of beds concealing children. As dirty and dishevelled as the room itself, these feral fairies in nightgowns and slippers orchestrate the action with the help of Puck (Alexander Knox). In what seems (nothing is clear here, and not in a good way) to be a collective playing-out of escapist fantasy, the children dream their way out of their squalor while Puck himself, initially elderly and wheelchair-bound, casts aside his disability and regains his youth.

There’s no shortage of ideas here, but no amount of visual magic can distract from direction that lacks focus

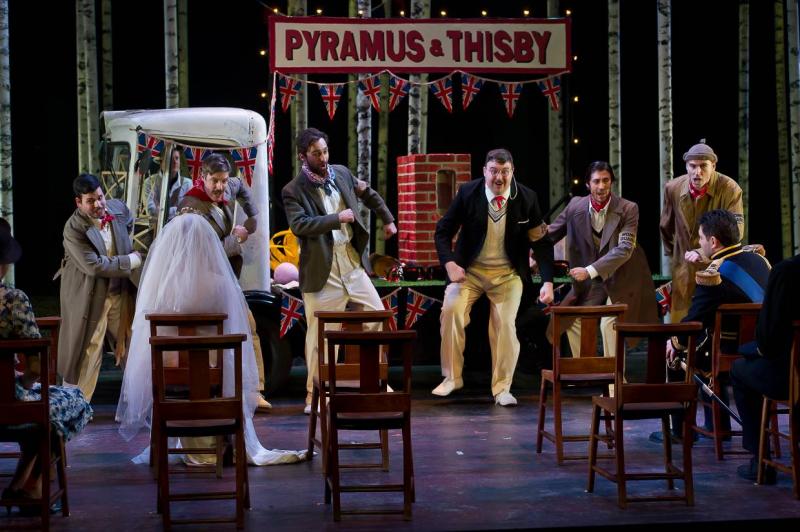

The quartet of lovers come clad in assorted service uniforms, while Oberon (Tom Verney) and Tytania (Eleanor Laugharne, pictured below) appear respectively as kinky surgeon (Oberon sports a rather fetching pair or leather trousers together with matching leather apron and gloves) and kinky matron (or possibly kinky nun – it’s hard to tell). The mechanicals fit into Lloyd-Evans scheme most naturally, with Quince (James Platt) heading up his plausibly motley collections of Home Guard volunteers.

There’s no shortage of ideas here, and while Dick Bird’s beautiful designs gamely pursue each one, conjuring flying beds and a rustic milk-float stage for Bottom et al, and bringing not only fairy-lights and bunting but an entire forest down from the sky, no amount of visual magic can distract from direction that lacks focus or any plan for his wartime setting other than some attractive visuals.

There’s no shortage of ideas here, and while Dick Bird’s beautiful designs gamely pursue each one, conjuring flying beds and a rustic milk-float stage for Bottom et al, and bringing not only fairy-lights and bunting but an entire forest down from the sky, no amount of visual magic can distract from direction that lacks focus or any plan for his wartime setting other than some attractive visuals.

It’s a lack that shows up the weaker actors of the cast. While there’s a place for motiveless malignancy in Shakespeare it certainly isn’t here, and despite stalking the stage like an extra from Saw, Verney’s villainous Oberon is strikingly lacking in character. Denied any relationship (amorous or otherwise) with matron Tytania, and with the “little Indian boy” all but absent, his campaign of mischief has little purpose and still less clarity. Vocally it’s a big ask for a young countertenor (particularly in a large space like the Barbican’s theatre) and while Verney’s diction and voice are both solid, we miss the magic only real legato can bring to “I know a bank” and the otherworldly menace Britten’s celesta insists so emphatically upon.

Laugharne’s Tytania is assured and queenly – the stand-out vocal performance of the evening – controlling a rather heavier voice than Britten’s writing suggests with absolute musicality. Among a universally strong quartet of lovers Sky Ingram’s passionate Helena (pictured below with Ashley Riches and Stuart Laing) and Riches’s Demetrius draw eye and ear, and there’s strong work also from Barnaby Rea as Bottom (alternating each performance with Ciprian Droma’s Theseus). While Rea delights in his comedy without ever sacrificing tone colour and phrasing, perhaps his fellow mechanicals might have taken more risks however; smaller roles like Flute (Jorge Navarro-Colorado) Snout (Luis Gomes) and Starveling (Hadleigh Adams) needed more character-singing and less vocal loveliness to bring energy to their knockabout scenes.

On the whole the pace did drag, and not even the excellent ensemble singing of the fairy chorus could redeem the directionless and dissonant work from the orchestra under Stephen Barlow. Britten’s evocative opening was lost in tentative scratchings, capturing the eeriness but none of the lush delights of this deviant forest of the night. At times too loud (a little more sympathy to Verney’s lower register might not have gone amiss) and at others crucially absent (the Act III lovers’ quartet needed much more support to make harmonic sense) the orchestra consistently hampered the singers – a real shame given their quality.

On the whole the pace did drag, and not even the excellent ensemble singing of the fairy chorus could redeem the directionless and dissonant work from the orchestra under Stephen Barlow. Britten’s evocative opening was lost in tentative scratchings, capturing the eeriness but none of the lush delights of this deviant forest of the night. At times too loud (a little more sympathy to Verney’s lower register might not have gone amiss) and at others crucially absent (the Act III lovers’ quartet needed much more support to make harmonic sense) the orchestra consistently hampered the singers – a real shame given their quality.

When Martin Lloyd-Evans’s production lost its fairies it also lost something of Shakespeare’s magic. Alden has flung the door wide for intelligent, resonant reworkings, but if a change of setting does nothing more than exchange crinolines for gas-masks then it hardly seems worth the trouble. There’s a comedy of mistaken identities here, but it’s not quite the one Britten had in mind.

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Add comment