Frankenstein, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Frankenstein, National Theatre

Frankenstein, National Theatre

Danny Boyle partially reanimates Mary Shelley's famous creation

Like the misbegotten monster at its heart, this stage version of Mary Shelley’s seminal novel is stitched together from a number of discrete parts; and though some of the pieces are in themselves extremely handsome, you can all too clearly see the joins. Here’s a bit of half-baked dance theatre, there a scene of simple, touching humanity. And for each dollop of broad ensemble posturing, there’s a visually stunning scenic effect.

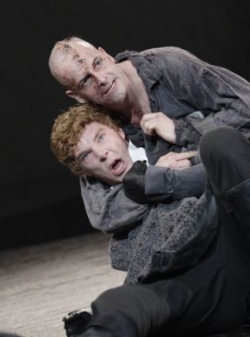

In truth, this double casting never really proves itself much more than a gimmick. It points up the inescapable bond shared by creature and creator, and in both Danny Boyle’s production and Nick Dear’s adaptation, the doppelgänger theme is to the fore. But it would take an inattentive spectator to miss these preoccupations, even without the heavy underlining of them that the role-swapping supplies. As an actor, Cumberbatch has the edge: there’s more rich detail to both his interpretations. But while there are differences of inflexion between the two pairings – Cumberbatch’s monster is bitterly witty and Miller’s more brutish, while Miller’s Frankenstein is more Byronically smouldering than Cumberbatch’s frostily acerbic version – they aren’t so significantly appreciable as to justify a second viewing.

As for Boyle’s production, at its best, it is startling and atmospheric; at its worst, it has you marvelling that a director so well-regarded for his film work should have produced something so stagey. And if the presence of electronic duo Underworld supplying the score sounds promising, in practice their music – a blend of unearthly chorales and folksy tunes – is disappointingly low-key and underused. Beautifully lit by Bruno Poet and designed by Mark Tildesley, the action begins well, with the clanging of a great bell suspended above the stalls. From a shaft of shining metal hang myriad gleaming bare bulbs, which flare into blazing, blinding light, generating a palpable heat.

On stage an amniotic membrane stretched across a circular frame begins to bulge and strain, until finally it bursts open, disgorging the Creature. Naked, half-bald and and criss-crossed with crude stitching, he is an unsettling sight – if scarcely as horrifying as the response of those who later encounter him would suggest. Slowly, agonisingly at first, he finds his feet, stumbling and wobbling like a toddler before eventually breaking into a delighted run. One glance from his maker, in an all too cursory first scene between them, is enough to convince Victor Frankenstein to cast out the misshapen fruit of his labour (in both senses of the word, given the birthing imagery); and the Creature rushes out into a world that quickly proves hostile.

And here the production takes its first false steps. A skeletal steam train, all metallic racket, whirling cogs and passengers in grotesque goggles with blackened faces, comes roaring out of the murk – it’s infernally Miltonic, and a strikingly dark, Satanic image of a burgeoning industrial age, but its aesthetic is thereafter abandoned. Worse, it’s adorned with cod business with busty prostitutes and urban street denizens that makes the sequence feel almost sub-Les Misérables.

And here the production takes its first false steps. A skeletal steam train, all metallic racket, whirling cogs and passengers in grotesque goggles with blackened faces, comes roaring out of the murk – it’s infernally Miltonic, and a strikingly dark, Satanic image of a burgeoning industrial age, but its aesthetic is thereafter abandoned. Worse, it’s adorned with cod business with busty prostitutes and urban street denizens that makes the sequence feel almost sub-Les Misérables.

It’s not much of an improvement when the Creature stumbles upon a rural shack owned by a kindly old blind man (Karl Johnson) that looks like a greenhouse with Blakeian imagery on its flimsy walls. Here, in a series of scenes that veer between the touching and the dramatically creaky, he begins his education, develops a taste for Paradise Lost, and, during an entirely superfluous dream ballet, conceives of the notion of a female creature to share his lot, reviled as he is by society.

By the time he arrives to confront Frankenstein in Geneva, where Victor (Cumberbatch, pictured above right with Miller's Creature) is due to wed his lovely and decidedly broody cousin Elizabeth (Naomie Harris), the Creature is prepared for some well-turned disputation, and ready to demand the creation of his mate.

Anyone who’s read the original novel will know it’s a cumbersome work. Dear’s adaptation is fleet by comparison, and some of his writing has a bracing immediacy; the Creature’s brief moment of connection with Elizabeth, soon so brutally severed, is especially memorable. The themes he highlights, of scientific responsibility, justice, conformism, social hierarchy, are undeniably resonant, with the nature/nurture question – who is the true author of the monster’s murderous acts? – particularly pertinent in a week in which the news reported psychologists’ claim to be able to detect the seeds of criminality in children as young as three. But elsewhere the writing is conspicuously awkward, and it is helped not at all by some decidedly coarse acting, notably in the household of Frankenstein père, clumsily played by George Harris.

Still, the story has a timeless compulsion; and this version gives the Creature a powerful and poignant voice in which to speak. Notably, it’s often at its most eloquent when there’s no actual dialogue: when the monster gambols, with childlike pleasure, in the sun or rain, chases snowflakes in rapturous wonderment, or quails in fear and hurt from a stick or a boot. It’s a shame that what surrounds him isn’t more consistent or coherent.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Beautiful Future is Coming / She's Behind You

A deft, epoch-straddling climate six-hander and a celebration (and take-down) of the pantomime dame at the Traverse Theatre

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Good Night, Oscar, Barbican review - sad story of a Hollywood great's meltdown, with a dazzling turn by Sean Hayes

Oscar Levant is an ideal subject to refresh the debate about media freedom

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews - Monstering the Rocketman by Henry Naylor / Alex Berr

Tabloid excess in the 1980s; gallows humour in reflections on life and death

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Lost Lear / Consumed

Twists in the tail bring revelations in two fine shows at the Traverse Theatre

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Make It Happen, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tutting at naughtiness

James Graham's dazzling comedy-drama on the rise and fall of RBS fails to snarl

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: I'm Ready To Talk Now / RIFT

An intimate one-to-one encounter and an examination of brotherly love at the Traverse Theatre

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Top Hat, Chichester Festival Theatre review - top spectacle but book tails off

Glitz and glamour in revived dance show based on Fred and Ginger's movie

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Alright Sunshine / K Mak at the Planetarium / PAINKILLERS

Three early Fringe theatre shows offer blissed-out beats, identity questions and powerful drama

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

The Daughter of Time, Charing Cross Theatre review - unfocused version of novel that cleared Richard III

The writer did impressive research but shouldn't have fleshed out Josephine Tey’s story

Add comment