Rose Wylie, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings | reviews, news & interviews

Rose Wylie, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings

Rose Wylie, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings

The buoyant paintings of an artist with a singular vision

The Jerwood Gallery on Stade beach in Hastings has so far had a fraught if very short history. Local opposition, largely from the neighbouring fishing community, have campaigned relentlessly against the gallery, fearing that it would ruin the Stade's rustic charm and bring little or no benefit to most locals.

Social and economic concerns aside, it's difficult to see what the fuss is about when you consider the gallery architecturally. It has a modest silhouette from the street and it’s sensitively clad in glossy black ceramic tiles that pay some deference to the adjacent net shops and huts, as well as reflecting the huge seaside horizon and surrounding old town buildings and hills. The inside is kept simple with white walls, wooden slats and pale terrazzo all flooded with sunlight from generous windows and a glass-walled courtyard.

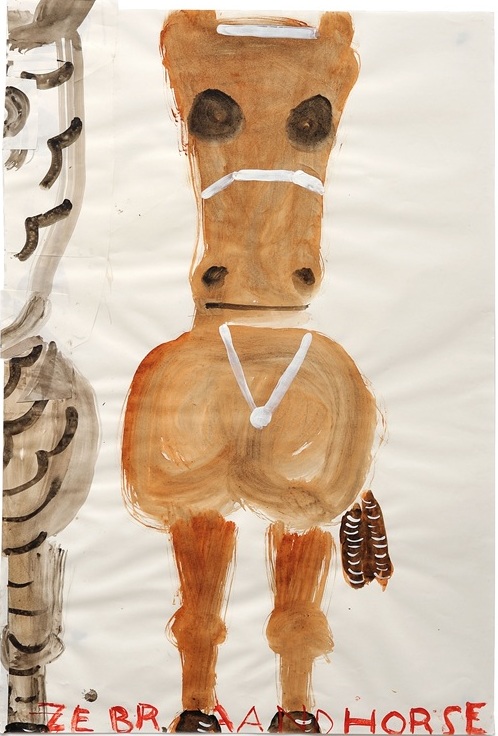

For the inaugural show we are treated to a retrospective of the work of Rose Wylie (pictured, Zebra Horse, 2009), the new septuagenarian star who has broken art-world convention by peaking so late in her career. As such, she has been the subject of as much feature-writing as criticism. Big Boys Sit in the Front caps a long association with the Jerwood and a slew of media coverage around her recent international successes.

For the inaugural show we are treated to a retrospective of the work of Rose Wylie (pictured, Zebra Horse, 2009), the new septuagenarian star who has broken art-world convention by peaking so late in her career. As such, she has been the subject of as much feature-writing as criticism. Big Boys Sit in the Front caps a long association with the Jerwood and a slew of media coverage around her recent international successes.

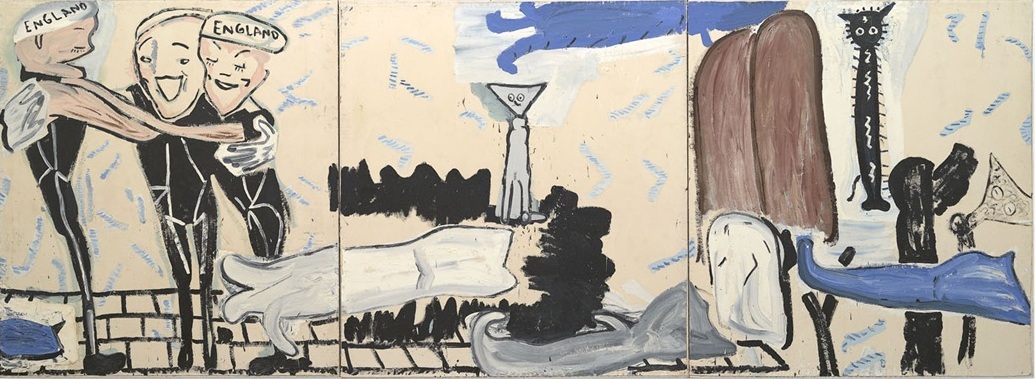

It’s easy to assume Wylie is younger, as many people have done, because the paintings are executed on such an enormous scale. Getting Better with Water, 2011, comprising four large panels, is almost too big to fit between the ceiling and the floor. Running 16ft around the corner of the main room is a frieze-like combination of Swimming With Cats (Blue Twink), 2002 (pictured next page), Green Twink and Ivy and Red Twink and Ivy, 2002 (main picture) where raw, possibly un-primed canvas deadens much of the brushwork save for richly slathered patches of pea-green, blue and red, roughly delineated with syrupy daubs of black that register a quick but considered pace. The lines peter out and pick up where they left off with generous reapplication before fading again to translucence.

Wylie’s carelessness is thrilling in these details, and you get a vicarious buzz from her devil-may-care attitude as you trace the paint over the canvas. The bright smiles of swimmers with their dimples and eyelashes have a postcard feel to them, but also the fluid, confident touch of a gifted draughtswoman.

Not that these are lazy pictures. Splats of paint tell us that these canvases spent some time on the floor, and rethinking is much in evidence in the rough-hewn and peeling patches of canvas stuck to the surfaces. When it comes to placing Wylie’s work schematically, many late-20th-century painters spring to mind, particularly the Americans Phillip Guston and Jean-Michel Basquiat. But there's a buoyancy in these pictures that those don’t have, leaving the impression that Wylie's vision is singular.

Repetition underscores the work of recollection

The thread through all the pictures is recollection, be it of film scenes, newspaper stories or conversations. Wylie has said herself that she draws from memory and the drawing comes first. “Drawings look like how I see,” she says. “And the paintings look like the drawings.” There’s a lot of painted text, too. Getting Better with Water seems to recall an interview with swimmer Rebecca Adlington. The scrawled question, “What do you most dislike about yourself?” is answered “BIG SHOULDERS” in capitals that intersect the fussy figure of the swimmer who’s enveloped in a comic-like starburst.

Repetition in many of the paintings underscores the very work of recollection. In Kill Bill (Film Notes), 2007, painted from the memory of a scene in the film, Wylie paints two versions side by side, with one showing Uma Thurman's blonde crown as she overlooks a brutally vanquished body lying over an absurdly bright pool of blood. As well as echoing the celluloid’s gradual frame-shifts, the nixed duplication demonstrates that memory is something we work at and this labour of piecing things together finds many forms in the show, in the jigsaw motif, the continual patching and reconfigurations of elements. “What you see is as important as the food you eat,” she says in the video, and it’s sharing her delight in reconstructing lost moments that leaves a lasting impression.

- Rose Wylie at Jerwood Space, Hastings until 1 July

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Add comment