Conlon Nancarrow Weekend, South Bank Centre | reviews, news & interviews

Conlon Nancarrow Weekend, South Bank Centre

Conlon Nancarrow Weekend, South Bank Centre

Memorable celebration of an American musical maverick

This has to be the only music festival I've ever been to where two vacuum cleaners were on standby in case the star performer conked out. But that's what happens when your star performer is a player piano - they seem to run on Hoover tubes. With 11 concerts and one film in two days, this celebration of American maverick Conlon Nancarrow was London's alternative marathon. One that was no less eccentric, exhausting or adrenalin-generating (though much less running-based).

At the core of the weekend was a nine-concert cycle of the complete studies for player piano. As far as anyone knew, it was the first time all 51 studies had been performed in public in one go. And while the logistics of the process demonstrated exactly why, by the end of the cycle, a part of me wished they came out on annual show, like the Bach Passions. For within the riotous explosion of mechanised music that they offer are some of the most fantastical sounds every imagined by man. Number one most fantastical is undoubtedly the "Nancarrow lick".

The highlight came from a late-night batch of studies that uncovered another side to Nancarrow. The Nancarrow of Latin America

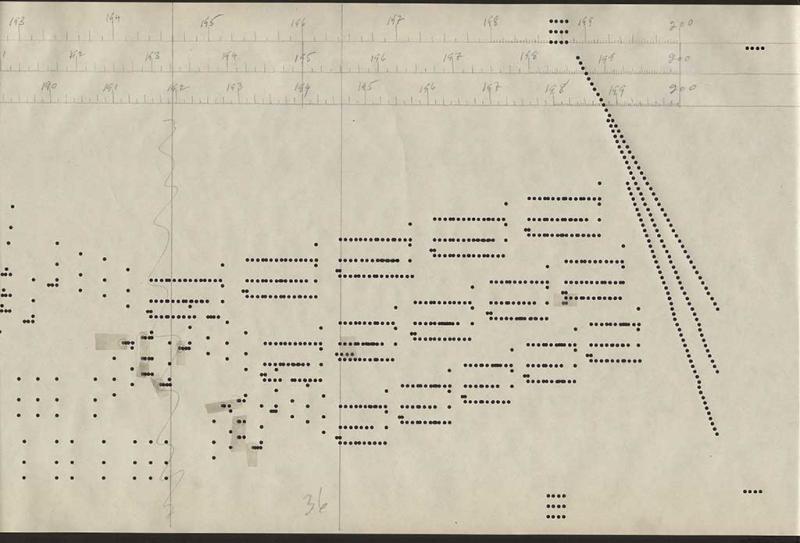

This classic Nancarrow manouever sees a fast-bowled arpeggio zig-zag its way down the full length of a keyboard with mechanical precision and thunderous determination. The result is a lightning strike in piano sound. One that frequently has one's soul diving for cover. There was a whole concert dedicated to the Nancarrow lick, which proved to be one of the most viscerally arresting sections of the weekend. It included the monstrous Study No 25 that - the superb programme notes told us - contained 1,028 notes in the final 12 seconds. There was also the explosively nervy Study No 43, and Studies 40 a and b that pitched two player pianos in a battle that ended in a deafening molten mush.

Fascinatingly, all this energy and excitement was being generated through the most intellectual of means. Virtually every study is built upon a variety of canons, in which different lines of music are juxtaposed in bafflingly complicated tempi relationships. None of the advanced maths gets in the way of the music, however. The musical material remains familiar and broad. The language of boogie-woogie, of Latin music, of the Baroque, of various recognisable 20th-century tongues, form a wide-ranging palette.

The result is a cycle that is overwhelming in its variety. Romantic lushness in 37. Music-hall tom-foolery in 18. An Oriental sunniness in 3c. A Brahmsian melancholy in 13. An acciaccatura-packed 36. Hindemith in 34. Purcell in 47. Serialism fused to pop in 31. And one of the most moving and loving visions of domestic bliss in Para Yoko, the only study with a dedication - to his third wife. The highlight, however, came from a late-night batch of studies that uncovered another side to Nancarrow. The Nancarrow of Latin America: breezy and bright. Here the music sways in a hammock (Study 6) or lies sozzled in the sun (Study 44).

This Latin interjection reminded us how important context was to all this experimentation. A information-rich documentary from Jim Greeson set the scene for Nancarrow's musical journey. Having joined the Lincoln Brigade to fight the Spanish Fascists, and returned to face an America hostile to his card-carrying Communism, Nancarrow was forced into exile in Mexico and virtual compositional seclusion. As with so many artistic break throughs, Nancarrow's experiments with the player piano was the consequence of necessity.

An eccentric life matched by an eccentric set-up. The Purcell Room recitals were compered by yarn-weaver, wizard-lookalike and pianola expert, Rex Lawson, and a German composer and piano roll-maker, Wolfgang Heisig, whose almost complete lack of English didn't stop him from trying to talk to us all day long.

Two fire-cracker works were dispatched with aplomb by Sinfonietta principal Joan Atherton and Rex the Wizard

But for a fully human line-up, you had to visit the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Here we got two beautifully curated concerts (hats off to Dominic Murcott) of non-player-piano work: early pieces for orchestra and several studies that had been transcribed for orchestra. None of these quite matched up to Nancarrow's short Toccata for violin and player piano and Piece for Tape (arranged for a live drummer by Murcott), two fire-cracker works dispatched with aplomb by Sinfonietta principal Joan Atherton and Rex the Wizard, and percussionist David Hockings.

Few would contend that Nancarrow's works for live performers are his best. So it wasn't surprising that his pieces were somewhat upstaged by a performance of John Cage's number piece, Five, by the London Sinfonietta on beguiling form, and a thrilling rendition of James Tenney's Spectral Canon for Conlon Nancarrow by Lawson, which whirled through the overtone series building itself up into an intergalactic lather. The same thing happened in the second QEH concert on Sunday: a stunning rendition of Ligeti's otherworldly Second String Quartet by the Arditti Quartet upstaging Nancarrow's two own attempts. No matter. The player piano had done its job. Nancarrow's fizzy musical world had taken up residency in my bones.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Add comment