Matthew Bourne's Early Adventures, Richmond Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Matthew Bourne's Early Adventures, Richmond Theatre

Matthew Bourne's Early Adventures, Richmond Theatre

The choreographer's first works make an evening of gay, charming entertainment

Matthew Bourne’s charm is a rare and cheering thing in the world of dance - a night out with three of his earliest works, Spitfire, Town & Country and The Infernal Galop, is akin to sitting down to watch Father Ted or Dad’s Army. It’s clever, often witty, always gay, and kind.

It’s only because I feel the richer pathos and ambiguity that Bourne later went on to tap in Swan Lake and Play Without Words, that I find the substantial evening a bit too much dessert by the time we reach The Infernal Galop. Still, this programme is just the ticket for a delicious little theatre on its touring circuit like Richmond Theatre, and its content on Jubilee weekend serendipitous, judging by last night's audience reaction. If any choreographer has the English sensibility down pat, it’s Bourne.

The three pieces inhabit a favourite Bourne era, nostalgic post-war fantasy, a world of movies, radio and magazine adverts, of ‘Allo ‘Allo, Blitz spirit and ITMA, with white long johns under stiff upper lips. There’s a sense of a young choreographer casting about in a series of sketches, but the finest ones are truly memorable: in Town & Country the two club gents trying to hide their feelings for each other and the hilariously speeded-up Brief Encounter, in The Infernal Galop the man in the dressing gown mooning on the floor like a stranded seal while beset by fantasy matelots.

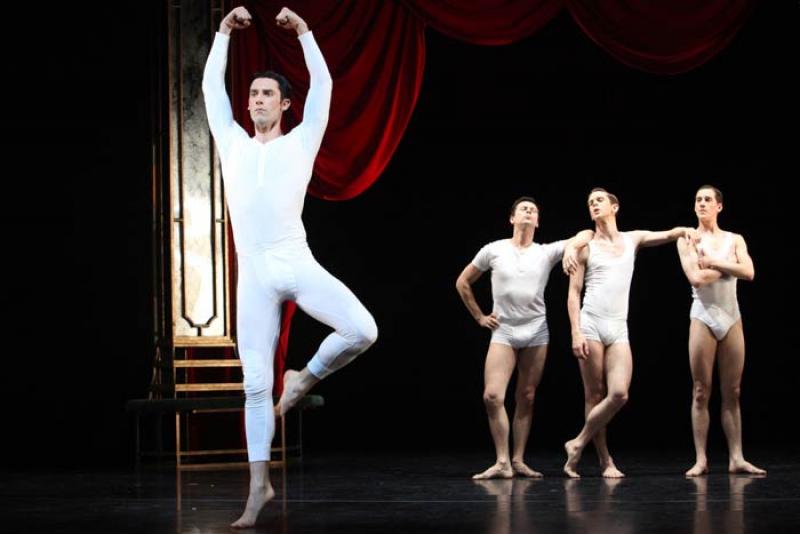

Spitfire is the underwear advert that made Bourne’s name for naughtiness in 1988, soon after he launched his idiosyncratic little dance-theatre troupe, Adventures in Motion Pictures. Its aplomb shows a natural showman already in full fig. By contrast, his cast are not in full fig, stripped to white Y-fronts and vests, posing carefully with clenched fists and knitting themselves into finely purled combinations, all with a sophisticated echo of an iconic Pas de Quatre of 1841 that fielded the four greatest ballerinas of the day on stage together.

The killer punch in this is that the music is from one of the great bravura classical pas de deux, Don Quixote, a competition stopper the world over, giving the grandest of expectations as these men make their appearance. The steps may not be bravura, but the deadly looks are nuclear, and the tiny flecks of classical references in the struttings are a joy to recognise (rather as Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo give joy to habitués).

Above, the video trailer for the Early Adventures programme

The Infernal Galop, the programme’s closer, was the next in Bourne’s canon, in 1989, a French revue ("with English subtitles", it says ironically) staged by the already brilliant designer Lez Brotherston with maximum bang from very small bucks: a tilted Paris newspaper kiosk, a pissoir encircled by an onomatopoeic choice of advert, “Byrrh” (an apéritif of red wine and quinine). The programme is equally a reminder of Brotherston’s inspired mastery as the wizard of Britain's dance stage the past quarter-century.

The galop does swing about infernally - if the man in the dressing gown, yearning for sailors to the seductive strains of “La Mer” is the highlight, the opposite is a lavatorial sequence in the pissoir, but Bourne works as hard on his material as fine TV comedy-writers, so you can’t be bored. He lands with deliciously languid (and English) irony on Offenbach's can-can, a line of supremely reluctant and worldlywise people, refusing to do more than very slightly lift a leg.

The galop does swing about infernally - if the man in the dressing gown, yearning for sailors to the seductive strains of “La Mer” is the highlight, the opposite is a lavatorial sequence in the pissoir, but Bourne works as hard on his material as fine TV comedy-writers, so you can’t be bored. He lands with deliciously languid (and English) irony on Offenbach's can-can, a line of supremely reluctant and worldlywise people, refusing to do more than very slightly lift a leg.

The most work that throws most balls forward to Bourne's later work is the middle one, Town & Country, a two-part romp around a Miss Marple world of English identity. The emotional unbuttoning of club gents and horsey society folks in Town is done most amusingly, without being satirical (Bourne’s a student of human nature, rather than of human behaviour). A speed-of-light skit on Brief Encounter is wonderful, with the pair of lovers and their waiter doubled (a device he used to powerful effect later in Play Without Words - to be seen later this summer at Sadler’s Wells). Christopher Marney, Dominic North and Tom Jackson Greaves are stand-outs in an outstanding little company of nine, so adept in timing that they can evoke both laughter and sympathy.

And almost as rewarding, Bourne's schoolboy games of homage to Frederick Ashton, Britain’s great ballet choreographer to whom in spirit he is so akin - four yokels in Country jocularly milk imaginary cows (see Façade), persist in clog-dancing (see La fille mal gardée), and mug and gurn ferociously at each other in their smocks (ok, see Benny Hill). I was trying to think of the visual equivalent of double-entendre - double-voir? Whatever it is, Bourne's doing it.

And almost as rewarding, Bourne's schoolboy games of homage to Frederick Ashton, Britain’s great ballet choreographer to whom in spirit he is so akin - four yokels in Country jocularly milk imaginary cows (see Façade), persist in clog-dancing (see La fille mal gardée), and mug and gurn ferociously at each other in their smocks (ok, see Benny Hill). I was trying to think of the visual equivalent of double-entendre - double-voir? Whatever it is, Bourne's doing it.

Deep down, is anything serious going on? One of his musical choices is Percy Grainger's "In a Nutshell Suite: Gay but Wistful". I think Bourne’s hugely interested in sex, in secret sex above all - and he contrives to disguise, expose and celebrate something frightfully English about it in all number of theatrical ways. This year’s retrospective provided by Sadler’s Wells gives us an interesting timeline to view. In the early adventures with dance-theatre, he was polishing his arts of concealment. Later on, in Swan Lake and Play Without Words (and - let’s hope - in his forthcoming Sleeping Beauty next winter too? It’s ripe material) he would use his concealing arts to make bittersweet points about pain too.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment