Luise Miller, Donmar Warehouse | reviews, news & interviews

Luise Miller, Donmar Warehouse

Luise Miller, Donmar Warehouse

Young lovers manipulated to a tragic end speak across the centuries

Time lurches when you see a historical play. But is it a case of autre temps, autres moeurs, or of plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Either way, the history needs to slap your face hard with recognition. Schiller’s Luise Miller is a 1784 play that clearly fires at its own vicious contemporary world, a catastrophically corrupt and unruly coalition of German states, and is its world just too far from our own to believe in the tragic young lovers at its core?

Mike Poulton has written a new English version that re-mints the flawed heroes and pieces of appalling human crud fighting through a blasted jungle of politics where love has nothing to do with anything, and young people’s idealism comes to a bad end. This is a more domestic take on the disposability of true feelings that Schiller portrayed in his later royal plays Don Carlos and Mary Stuart, both ringingly staged by Grandage in the past, this time with a vulnerable 16-year-old fiddler's daughter as its heroine. Schiller was only 24 when he wrote it, and it's the robust physical promise and sweetness of youth that this production homes in on, with much poignancy.

The period costumes, cravats, brocades and jewels are worn with modern hair - the then-and-now look feels fresh, and the verbal delivery by the cast is fast and up to date. The girl at the centre of the story is the merest pawn of male controlling urges, her young boyfriend (who will kill her), her protective father and her boyfriend’s pitiless, immoral father, machinating to protect his own status by any means however foul. There are girls on the run in Britain today escaping from just such situations; this play feels alive.

The period costumes, cravats, brocades and jewels are worn with modern hair - the then-and-now look feels fresh, and the verbal delivery by the cast is fast and up to date. The girl at the centre of the story is the merest pawn of male controlling urges, her young boyfriend (who will kill her), her protective father and her boyfriend’s pitiless, immoral father, machinating to protect his own status by any means however foul. There are girls on the run in Britain today escaping from just such situations; this play feels alive.

Its weakness is that it tends to strain some of its characters' actions beyond credibility: Verdi's operas Luisa Miller and Don Carlos are probably better known than the source dramas, and certainly Schiller's play has “opera” written all over it. Luise is a jobbing musician’s daughter in love with the son of the German Chancellor - an impossible marriage in the circumstances. The play’s second half has a schematic improbability that undermines the formidable emotional force of the first, in which the youth’s attempts to free himself from his father’s degenerate world reveal, inexorably, that there are no limits to human corruptibility and cynicism in the political jungle.

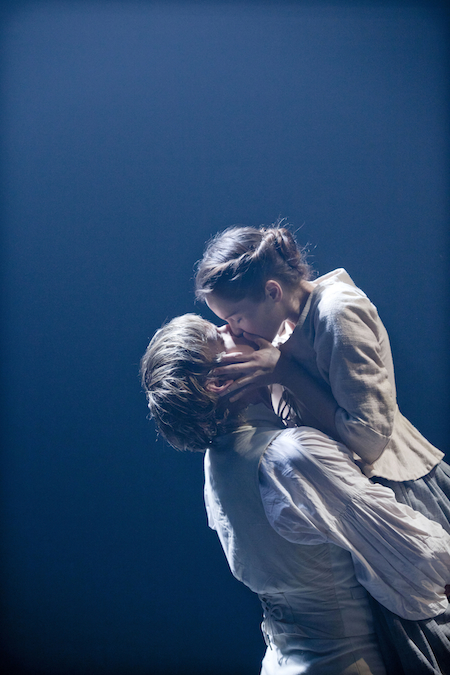

The question of the limits to the duty owed by young people to their parents, good or ill, surges up repeatedly - when Ferdinand fights his appalling father, holds a blade to his neck, young Luise is horrified: in her experience dads are loving and wise, and she will not accept that a son can disrupt the bond like this no matter what the provocation. (Pictured right, Max Bennett and Felicity Jones as the young lovers.)

It’s interesting how Schiller nailed the observation that young people, no matter how passionately they adore each other, can come to sudden rifts over half-understood ethical ideas, neither of them able to surmount their conditioning. Ferdinand can’t believe, given his court upbringing, that anyone can be totally incorruptible - Luise, who is as incorruptible as they come, can’t believe he could be so untrusting. The tragedy is not that they die, but that they die together in a misunderstanding, because he’s an idiotic fool. Even as the dying lovers kiss, you know he murdered her.

Max Bennett is terrific as the hotheaded young Ferdinand, very fit in his hussar’s uniform, and strongly physically attracted to Felicity Jones’s very young-seeming Luise, a girl shadowed by anxiety.

Finty Williams and Paul Higgins make an appealingly earthy, volatile couple as her parents, but Ferdinand’s father, the Chancellor, has to veer from comic villainy with the loathsome Wurm and the Mandelsonian Prince’s Chamberlain right over to pitiless monster, and the rangy, personable Ben Daniels (pictured left, with Max Bennett) was not quite warped enough to bluff his way through.

Finty Williams and Paul Higgins make an appealingly earthy, volatile couple as her parents, but Ferdinand’s father, the Chancellor, has to veer from comic villainy with the loathsome Wurm and the Mandelsonian Prince’s Chamberlain right over to pitiless monster, and the rangy, personable Ben Daniels (pictured left, with Max Bennett) was not quite warped enough to bluff his way through.

John Light’s Wurm, however, is as creepy and slithery as they come. Like an Iago, he has a deep coldness in his performance that makes something of the underworld about the heretical scene where he pulls an altarpiece out of his bag in order to force Luise to swear to a lie that will make her his slave. Schiller makes Wurm’s last words his threat to spill all the Chancellor’s filthy secrets to save his own neck - it seems all too likely that this toad could beat the rap. Cynicism wins.

Almost the best kept till last, there is a sumptuous performance in the otherwise dubious cameo part of Lady Milford, the despotic royal mistress who’s now threatened with deposition. Schiller gives her a picaresque backstory where, like Princess Eboli in Don Carlos, she tells how she used her beauty and intelligence “royally outfoxing all the royal foxes". Despite the impression that Lady Milford is shoehorned in somewhat expediently to keep the other characters sorted, Alex Kingston, with her velvety voice, plush bosom and rampant hair, is a wondrous presence, and her disappearance in Part Two in convenient self-exile casts a cloud over the rest of the play.

- Luise Miller is at the Donmar, London, till 30 July

- See what's on at the Donmar Warehouse

Placido Domingo sings the wounded Act II aria "Quando la sere al placido" from Verdi's opera Luisa Miller in a 1979 Covent Garden performance

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Othello, Theatre Royal, Haymarket review - a surprising mix of stateliness and ironic humour

David Harewood and Toby Jones at odds

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

Macbeth, RSC, Stratford review - Glaswegian gangs and ghoulies prove gripping

Sam Heughan's Macbeth cannot quite find a home in a mobster pub

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

The Line of Beauty, Almeida Theatre review - the 80s revisited in theatrically ravishing form

Alan Hollinghurst novel is cunningly filleted, very finely acted

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Add comment