Glamour of the Gods: Hollywood Portraits, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Glamour of the Gods: Hollywood Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Glamour of the Gods: Hollywood Portraits, National Portrait Gallery

Perfection on a glass plate: how the stars were shot before paparazzi

In the days before there were any paparazzi to catch celebrities unawares, the pictures of the stars that reached mere mortals like ourselves were carefully staged by the film studios. Establishments like MGM, Warner Bros and Paramount Pictures employed stills photographers to produce atmospheric shots of the action as it unfolded on the set and to make studio portraits of individual actors for release to adoring fans.

Photographers like Clarence Sinclair Bull, Greta Garbo’s favourite collaborator, and George Hurrell who imbued Joan Crawford and Marlene Dietrich with such smouldering allure, have since become famous names; rather than focusing on their iconic images, though, Glamour of the Gods takes a broad approach and includes the work of nearly 40 others. Yet because they created so many stereotypical images of the men and women of the silver screen, Bull and Hurrell’s seductive close-ups inevitably stand out.

All lines, freckles and moles have been removed and the skin whitened to become a marble-smooth mask

The most revealing exhibit is a photo of Crawford taken by Hurrell in 1930, which shows her warm-toned skin covered in freckles and her forehead etched with lines. This delightful shot makes her look intelligent and supremely human; beside it, though, is the negative covered with the marks of the retoucher’s brush and a print from the same series indicating the level of perfection he was aiming for. All lines, freckles and moles have been removed and the skin whitened to become a marble-smooth mask devoid of any signs of experience. Crawford’s face has been turned into a blank screen onto which admirers are invited to project their fantasies. "Your life, little girl, is an empty page that men will want to write on", sings Rolf in "Sixteen Going on Seventeen" from The Sound of Music, and the archetypal female star resembled an empty page on which men could inscribe their desires.

There were exceptions, of course. A still for Gone with the Wind (1939) shows Vivien Leigh with dirty clothes and dishevelled hair, her brow furrowed with the anxiety of her arduous return to Tara, the O’Haras' plantation, during the Civil War. The following year, though, in a portrait for the film Waterloo Bridge, Laszlo Willinger restored her to virginal beauty. With shining, back-lit hair and a faultless complexion, she demurely reclines in a frothy white gown decorated with feathers; it's as though the tough cookie from Gone with the Wind had been replaced by an exquisitely fragile yet supremely seductive bird.

Garbo wins the prize, though, for milk-white perfection and glacial cool. Bertram Longworth photographed her for Flesh and the Devil (pictured left) with co-star John Gilbert, who leans over her supine form to plant a kiss on her cheek.

Garbo wins the prize, though, for milk-white perfection and glacial cool. Bertram Longworth photographed her for Flesh and the Devil (pictured left) with co-star John Gilbert, who leans over her supine form to plant a kiss on her cheek.

Her face is a mask of dreamy acquiescence; female stars may arouse passion, but only bad girls have sexual appetites of their own. Men (the inscribers) are either seen in action, showing signs of effort like sweat, dirt and dishevelled hair, or are empowered by props such as guns, pipes and uniforms.

Clarence Sinclair Bull dares to show Gary Cooper sitting quietly alone (pictured below). Yet subtle details suggest that, unlike his female counterparts, he is master of his own destiny; by focusing on the star’s forehead, eyes, ears and nose, Bull implies thought and intelligent awareness.

Clarence Sinclair Bull dares to show Gary Cooper sitting quietly alone (pictured below). Yet subtle details suggest that, unlike his female counterparts, he is master of his own destiny; by focusing on the star’s forehead, eyes, ears and nose, Bull implies thought and intelligent awareness.

But the most prominent feature of the picture is the unlit cigarette projecting from the actor’s mouth; since Cooper isn’t smoking it... as yet... the only function of this phallic protuberance is to imply intent.

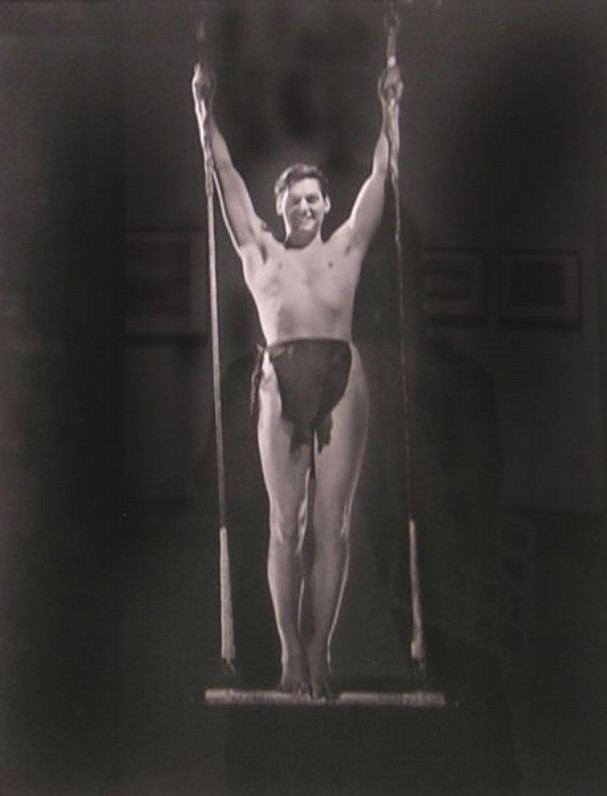

The oddest and most uncharacteristic shot is Bull’s photo of Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan. Wearing nothing but a leather apron that gives his hips a rather feminine curve, the Olympic swimmer smiles down at us from a trapeze on which he balances on tiptoe.

The oddest and most uncharacteristic shot is Bull’s photo of Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan. Wearing nothing but a leather apron that gives his hips a rather feminine curve, the Olympic swimmer smiles down at us from a trapeze on which he balances on tiptoe.

To hold onto the ropes, he stretches up his arms in the position of surrender; this exposes his smooth body to view and makes him look strangely vulnerable. Ironically in this shot, the man who plays one of the most athletic roles in all Hollywood looks like a gay icon – being rather than doing.

- Glamour of the Gods: Hollywood Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery until 23 October

- Read theartsdesk Q&A: Script supervisor Angela Allen

- Film gallery on theartsdesk: Weddings and Movie Stars

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment