Bobby Fischer Against the World | reviews, news & interviews

Bobby Fischer Against the World

Bobby Fischer Against the World

Superb documentary explores the thin line between genius and insanity

Chess grand masters have a reputation for possessing the kind of brilliance that’s inclined to tip into madness. Victor Korchnoi claimed he'd played against a dead man, while Wilhelm Steinitz insisted he'd played chess against God by wireless.

No film-maker could hope to delve inside the infinite tangle of wiring in Fischer’s brain, but Liz Garbus’s documentary depicts his scintillating ascent and ugly, tragic fall with almost dream-like luminosity. Chess aficionados may feel a little disappointed that the film doesn’t spend too much time fixating on the game’s minutest nuances, but there’s plenty here to evoke the colossal scale of Fischer’s abilities, whether it’s contemporary newsreel footage or thoughtful commentaries by some well-chosen eyewitnesses.

Garbus has tracked down Dr Anthony Saidy, a close friend who sheltered Fischer from the rampant media pack just before his apotheosis in Reykjavik, former US chess champion Larry Evans (who died last year) and Garry Kasparov, a Russian champion from a later generation. All of them throw revealing light on Fischer’s personality and on the Cold War political climate in which he soared to a unique kind of stardom.

Garbus has tracked down Dr Anthony Saidy, a close friend who sheltered Fischer from the rampant media pack just before his apotheosis in Reykjavik, former US chess champion Larry Evans (who died last year) and Garry Kasparov, a Russian champion from a later generation. All of them throw revealing light on Fischer’s personality and on the Cold War political climate in which he soared to a unique kind of stardom.

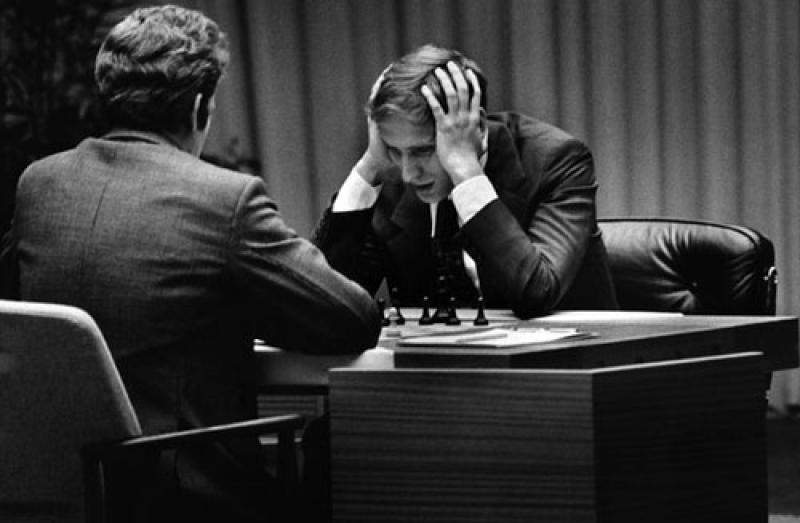

Garbus’s smartest coup was to bring aboard Harry Benson, a Scottish photographer working for Life magazine who achieved the virtually unheard-of status of confidant to Bobby Fischer. As well as reminiscing about the Fischer he evidently knew pretty well, Benson has contributed an archive of superb and previously unseen black-and-white photographs of Fischer in a variety of locations, most strikingly training in his gym and swimming pool as he prepared for the battle against Spassky.

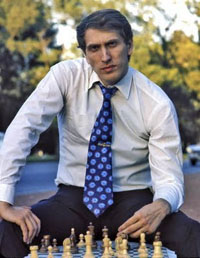

His willingness to parade his physique in front of Benson’s lens suggests an exhibitionist streak usually hidden behind Fischer’s media-shy reclusiveness. In his youth, before he descended into anti-Semitic lunacy and dressed like some deranged old Bowery bum, Fischer even had glimmerings of pin-up potential.

The film skilfully tints in the story’s social and historical background, with help from shrewdly chosen pop records (not least Yes's "Your Move") and descriptive music by Philip Sheppard. Fischer's intellectual brilliance surely owed much to his mother, Regina, who not only had a PhD in haematology but also a hefty FBI file tracing her communist links and history as a high-profile protester against the Vietnam War.

The film skilfully tints in the story’s social and historical background, with help from shrewdly chosen pop records (not least Yes's "Your Move") and descriptive music by Philip Sheppard. Fischer's intellectual brilliance surely owed much to his mother, Regina, who not only had a PhD in haematology but also a hefty FBI file tracing her communist links and history as a high-profile protester against the Vietnam War.

The identity of Bobby’s father has never been conclusively settled – it was either Hans Gerhardt Fischer, whom Regina met while studying medicine in Moscow in the 1930s, or Paul Nemenyi, whom she first met while a student in Denver. In any event, Bobby’s obsession with chess from the age of seven crowded out virtually everything else in his life, so that his default condition became a rarefied loneliness.

It was a historical accident that Fischer’s bid for the world title should become a kind of proxy for the ongoing geopolitical struggle between the USA and the USSR, but it proved an irresistible angle for the media. Henry Kissinger even pops up to recall how he felt that “it would be good for America and good for democracy to have an American winner”, while Kasparov describes how the Soviets were desperate to score a propaganda victory against the decadent West, and chess was their favoured tool. Fischer, too, seemed to feel a patriotic urge to zap the Russkies, though the courteous and tolerant behaviour of his opponent showed that Spassky was no mere puppet of the Kremlin.

Indeed, had Spassky merely insisted on adherence to the rules, and not agreed to Fischer's demand to hold their match in a small ante-room behind the main stage, he would have won the bout by default. As it was, he was man enough to applaud Fischer's performance in the critically admired Game 6 ("like a symphony of placid beauty", according to Saidy), and seemed to feel that Fischer's overall victory was richly deserved.

And with that, it was as if Fischer's great mission was accomplished. After much haggling over rules and prize money, he declined a subsequent challenge from Anatoly Karpov, and forfeited his title. He took refuge with the fundamentalist-inclined Worldwide Church of God in Pasadena, and grew increasingly paranoid, fearing that he was the victim of "radioactive espionage" by the Russians and running scared of an imaginary threat from Mossad. A rematch with Spassky in 1992 was a dismal parody of the original, and also put Fischer on the USA's wanted list, since he'd broken an official embargo by playing in war-ravaged Yugoslavia.

And with that, it was as if Fischer's great mission was accomplished. After much haggling over rules and prize money, he declined a subsequent challenge from Anatoly Karpov, and forfeited his title. He took refuge with the fundamentalist-inclined Worldwide Church of God in Pasadena, and grew increasingly paranoid, fearing that he was the victim of "radioactive espionage" by the Russians and running scared of an imaginary threat from Mossad. A rematch with Spassky in 1992 was a dismal parody of the original, and also put Fischer on the USA's wanted list, since he'd broken an official embargo by playing in war-ravaged Yugoslavia.

He took refuge in Japan, from where he gave a notorious radio interview exulting in the 9/11 attacks on New York, then when the Japanese authorities proposed to extradite him to the US, Iceland rescued him by giving him citizenship. He remained in the country which hosted his most memorable triumph until his death, growing increasingly deranged and obsessive. Garbus has created a resonant requiem for chess's mad, dead king.

Q&A with director Liz Garbus

Adam Sweeting: There's a sense that there's a correlation between great chess players and brilliant musicians or mathematicians. Do you feel that's true of Bobby Fischer?

LIZ GARBUS (pictured left): Bobby's mother was a remarkable woman, a genius and a political activist, but she was out of the home. She worked two jobs so she was not around, and Bobby lived quite a deprived childhood. He was quite alone and chess is what brought him up and that was his development.

LIZ GARBUS (pictured left): Bobby's mother was a remarkable woman, a genius and a political activist, but she was out of the home. She worked two jobs so she was not around, and Bobby lived quite a deprived childhood. He was quite alone and chess is what brought him up and that was his development.

I think sometimes with great artists, great composers or actors... now we see child actors who are burned out and exhausted and fried by the time they're 18, this is a problem about celebrity and relentless scrutiny. You don't know if people are friends with you because they care for you or if they're just trying to be associated with you, so there's a general feeling of suspicion. Of course many people can survive that, but some who perhaps have a proclivity for mental instability may not. Early on Bobby seemed to be able to have a little bit of a laugh at himself, but as time went on he lost that ability.

Was it the social context and the time in history that attracted you to the story?

Well, they don't exist without each other. You've got two superpowers in the midst of a Cold War armed to the teeth, on the verge of total disaster, right? And then you've got the Soviets who have made chess a demonstration, as Kasparov says, of their intellectual superiority over the West. It's part of national pride that they dominated the sport and dominated it for centuries, producing one world champion after the other. Then here comes this kid, sprouting up like a weed through the cracks. He had wonderful teachers but he also worked very much on his own.

There's the black and white of the bipolar Cold War order at that time, it was just the perfect storm to create Bobby Fischer

All of a sudden he makes national headlines, this kid could take on the best. His story doesn't exist without this Cold War context because nobody would have cared if it was a game against Finland. What was important was that he could take on the Soviets for the World Championship. The metaphors just keep coming because chess is war on the board, you've got two armies, the little pawns at the front are sacrificed first... then there's the black and white of the bipolar Cold War order at that time, it was just the perfect storm to create Bobby Fischer and how important that match was. They couldn't have existed without each other and that's what I was interested in. It was just part of the cultural pulse, y'know? It bumped Watergate to the second story in the news, it was that important.

But the Reykjavik match was also just a really dramatic contest too?

The 1972 match was a thriller, and it made for really entertaining material. There's Bobby's story and the cultural and political context, but at the heart of the film I hope is the thrill of that sports match. It's tremendous. There were so many ups and downs. Would Bobby go to Iceland? Would he not go? Then he loses at the beginning and it seems hopeless. It's like being down zero-two in the World Series. It's tough to come back.

Kasparov remembers watching Bobby play chess and people were rooting for him because they loved his play

Is it a particularly American story? In some ways Fischer isn't a quintessential American character, is he?

I think it's a much more universal rise-and-fall story of somebody who's built up to represent everything in a nation's hopes and dreams, not just the USA. It was an Englishman, James Slater, who made the move which made Bobby go and play in Reykjavik. Slater was a London businessman - he's still alive in fact - who doubled the purse for the match, so all the West was watching Bobby and the Soviets were watching Bobby. Garry Kasparov remembers watching Bobby play chess and people were rooting for him because they loved his play. It wasn't just for America.

How do you account for Fischer's decline into paranoia, anti-Semitism and so on?

I think it goes back to when he hadn't developed other parts of his personality. He achieved the one thing that had organised his entire life for 22 out of his 29 years. He always believed he was the best chess player in the world, but by becoming indisputably the best chess player in the world by winning the World Championship, the organising principle of his life was gone. Many people would try to defend their title and keep it for a while - Bobby in an early interview said he wanted to keep the title for 20 years.

But Bobby didn't have the capacity for that consistency. He was too erratic, and when 1975 came around and it was time for him to defend the title, he went in with another series of demands [which couldn't be met], and to me 1975 was really the beginning of the end for Bobby. Everything kind of got looser, it wasn't organised into blacks and whites. Bobby couldn't see the world outside of that and I think his anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism... I mean, what were the three things Bobby was? He was American, he was a chess player and he was Jewish, and all of those things he rejected. So it was a self-rejection.

Is there a clinical name for his mental condition?

Well, he was never seen by a doctor and diagnosed, but people close to him talked about paranoid psychosis. Also Bobby would call into these radio shows, and we've got 200 hours of mp3s of Bobby on these shows, ranting and ranting. It was like a train of thought that was almost unstoppable. It was not a well-thought-out, considered ideological position against America or against the Jews, it was like a train off the tracks just running without brakes. Bobby was never really political. He didn't want to beat the Soviets out of some sort of American sense of nationalism, he wanted to beat them because he wanted to be the best. He also thought the Soviets cheated at chess, which in fact he was able to prove. Sometimes with Bobby it was like "just because I'm paranoid doesn't mean they're not following me". The Soviets did organise for the easy ascension of their great players in matches, so there was some truth to his suspicions early on. It was the Cold War, so that kind of spy intrigue drama was part of the ether. We might have those kinds of suspicions about al-Qaeda today. If Obama was sitting down with an al-Qaeda member, we might think there was hanky-panky going on there too. It was that level of suspicion.

- Bobby Fischer Against the World opens on Friday 15 July

- Find Bobby Fischer Against the World DVD on Amazon

- Find Endgame - Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall by Frank Brady on Amazon

Watch the trailer for Bobby Fischer Against the World

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Add comment