Tread Softly/ Carnival of the Animals/ Comedy of Change, Rambert Dance, Sadler's Wells | reviews, news & interviews

Tread Softly/ Carnival of the Animals/ Comedy of Change, Rambert Dance, Sadler's Wells

Tread Softly/ Carnival of the Animals/ Comedy of Change, Rambert Dance, Sadler's Wells

Three of Britain's finest choreographers and great music on a triumphant mixed bill

At its best (ie when it’s not trying to be gimmicky and snare so-called “new audiences”), Rambert is unique in Britain in providing music and dance as theatre. No other company matches it in commitment to this, not even the Royal Ballet, which long ago adopted cloth ears when it comes to new ballet music.

Long ago Henri Oguike shone out among the younger generation of choreographers as exceptional in reading vibrantly athletic movement inside powerful music. Though his own company has never made it to Sadler’s Wells, at last he himself does, with a strikingly good new work for Rambert, set to Schubert’s Death and the Maiden string quartet, in Mahler’s lush orchestration. It’s so very rare to see choreography of such natural physicality and such freshly revealing musical sensitivity.

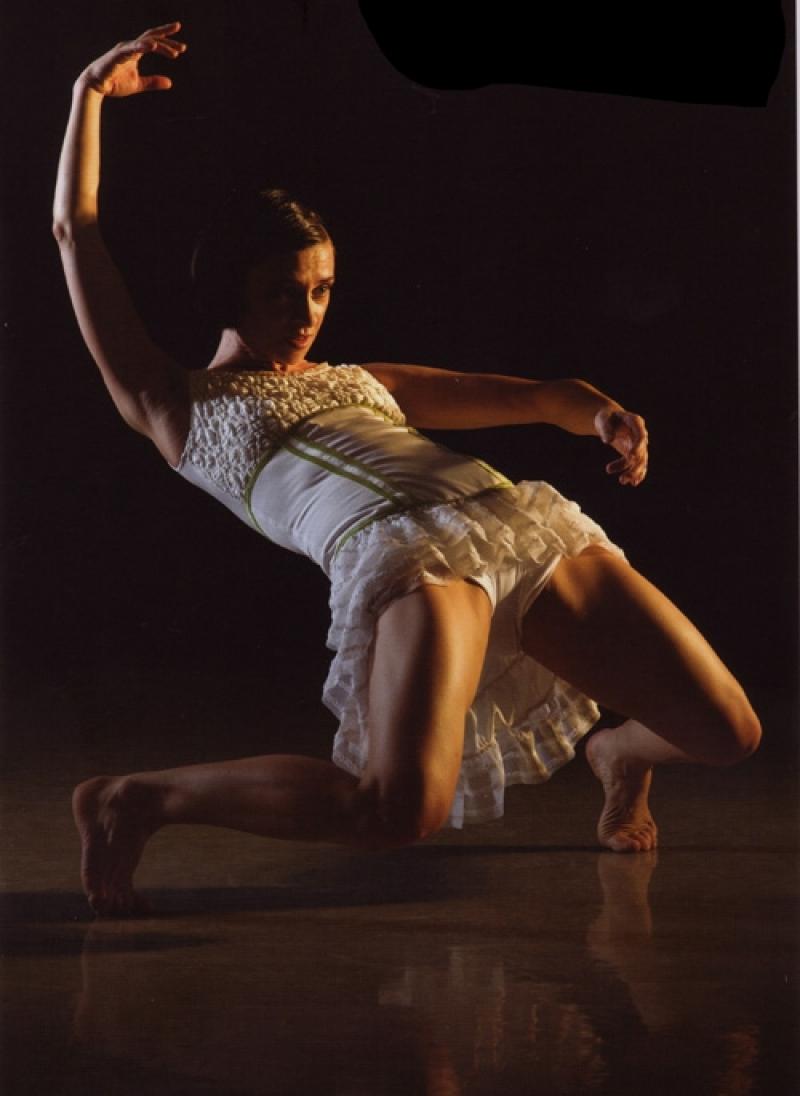

Tread Softly, the title, completes itself in W B Yeats’ line: “because you tread on my dreams”, and “dream” is the operative word. Not a nightmare of Death stalking the frightened Maiden, the usual motif, but the thoroughly modern Maiden dreaming of what the French call “the little death”, la petite mort, or orgasm. It begins with a woman sleeping and a man emerging from the dark, treading for a moment on her stomach. Yet this odd, rather artificial movement at once wakens her, and she strikes an arrestingly watchful position, like a medium fearlessly calling up other voices from the shadows - and this girl is not afraid of the dark.

The treading motif re-emerges in several different guises, in almost narrative storylets, where the four women, dressed in delicious chopped-off white flamenco dresses by Asalia Khadjé, and radiant in incredibly glamorous light by Yaron Abulafia, come across as powerful, sexually alert Amazons, while the six men range from rutting rituals with exciting little jumps and springs or an unsure lover petitioning his girl in intimate little duets.

Certainly the music, in Schubert’s dense, ruminative way, is too long and complete for any choreography to travel with it all the way. Yet Oguike gives it a vivid alternative life with his vigorous, nervy, almost African dance style. I was thinking watching it that possibly only Paul Taylor has such a natural instinct for physical momentum in choreography, but Oguike’s women are something else - the most unaffected and ripe femaleness I’ve seen in any choreography in Britain, strong, elegant, funny and fearless girls with an imaginative life that is inimitably 21st-century.

The finale is thrilling, with Schubert marshalling a frenzy of strings and Oguike marshalling the line of dancers aggressively sparring with us like boxers, or doing a ghost of the twist. It has arrogance, pride, and terrific chutzpah. Bravo, Oguike. And bravo too to the top-class playing by the newly named Rambert Orchestra under Paul Hoskins.

The guests in white tailcoats adopt echoes of animal behaviour like people who’ve had a smidgeon too much to drink

By polar contrast Siobhan Davies’s Carnival of the Animals is an allusive, quietly witty cocktail party to Saint-Saëns' picturesque little suite where the guests (and staff, presumably) in white tailcoats adopt echoes of animal behaviour like people who’ve had a smidgeon too much to drink.

A woman teeters slowly, falling forward and back in slow-motion, to the Elephant’s lumbering pace, and the fact that she is a lithe, graceful blonde makes it odder and funnier. A man confesses his love hopelessly to a chic creature with hand patting his heart to the call of the Cuckoo, while she smilingly evades him - it’s as charming as a cartoon by Peynet. Two women become Tortoises under huge fans of ostrich feathers. The company waltz captivatingly in blue rubber gloves in a Fairy-Liquid-green light for the Aquarium. The piece takes a little time to warm up (and I’ve seen more spirited performances of it in the past than this one), but its witticisms accumulate.

Finally, the most ambitious piece of Rambert’s year; Mark Baldwin’s new work with a commissioned score from Julian Anderson, inspired by Darwin, and called Comedy of Change. Much of this is superb: a magnificent score from Anderson, such a fine composer, particularly for dance for which he somehow allows air within his sumptuous, highly sprung and yet light-touched music - and a score that, even if it exists thanks to the Drummond Fund for dance commissions, begs also to be played in concert halls.

Finally, the most ambitious piece of Rambert’s year; Mark Baldwin’s new work with a commissioned score from Julian Anderson, inspired by Darwin, and called Comedy of Change. Much of this is superb: a magnificent score from Anderson, such a fine composer, particularly for dance for which he somehow allows air within his sumptuous, highly sprung and yet light-touched music - and a score that, even if it exists thanks to the Drummond Fund for dance commissions, begs also to be played in concert halls.

Baldwin, with his usual showmanship, has it dressed in flamboyant style with dinosaur eggs popping open at the beginning and spidery creatures crawling out, and some nonsense with a tinfoil cast made of a person at the end to provide an empty human carapace that must finally be squashed flat.

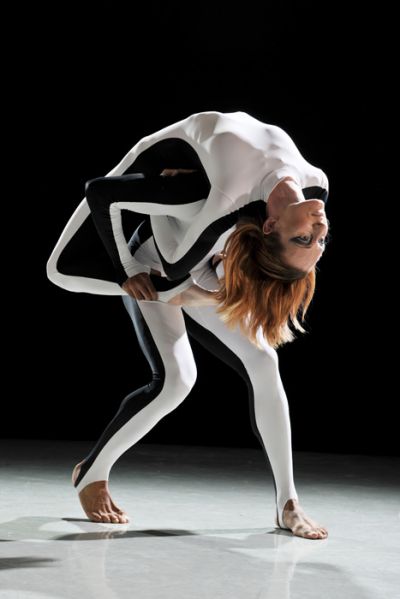

Poor Darwin is presumably to be blamed for these gimmicks, but between them Baldwin has created some of his most lyrically serious dance to Anderson’s lyrically serious music, a confident, constantly absorbing flow of invention that often makes something unusually interesting out of simple, uncluttered movements. This simplicity is etched cleanly into the space by the unitards, white-fronted, black-backed, by Georg Meyer-Wiel, and whose graphic possibilities Baldwin cunningly uses in the sculpting of jumps, groups and lifts. (Picture right by Hugo Glendinning/ Rambert)

In other words, Baldwin seems to be seeing his dance in all dimensions, aurally, visually, graphically and spatially, both in the planning and in the spontaneous accident. It's masterful - until the awful misjudgment of the last section where his stunning dancers who have looked so fantastic until then have to come on in ludicrous head-to-toe black leotards showing only their lips and eyes, like victims of cheap bondage sessions, and deal with the tinfoil man-cast. For almost all of this rich work, I imagine Darwin would find it hard to defend the idea that such accomplishment could ever have once started with one amoeba being stronger than another - but for that last bit, it’s back to slime cells, it seems.

- Rambert perform this programme at Sadler’s Wells till Saturday, book online here. Then Theatre Royal, Bath, 12-14 November; Theatre Royal, Norwich 25-27 November; Royal and Derngate, Northampton, 2-4 December; then again in the New Year. Tour information here.

- Read theartsdesk interview with Mark Baldwin about Comedy of Change

- Check out what's on at Sadler's Wells this season

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment