theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Anish Kapoor | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Anish Kapoor

theartsdesk Q&A: Artist Anish Kapoor

On spiritualism, nationality, psychoanalysis and the fourth plinth

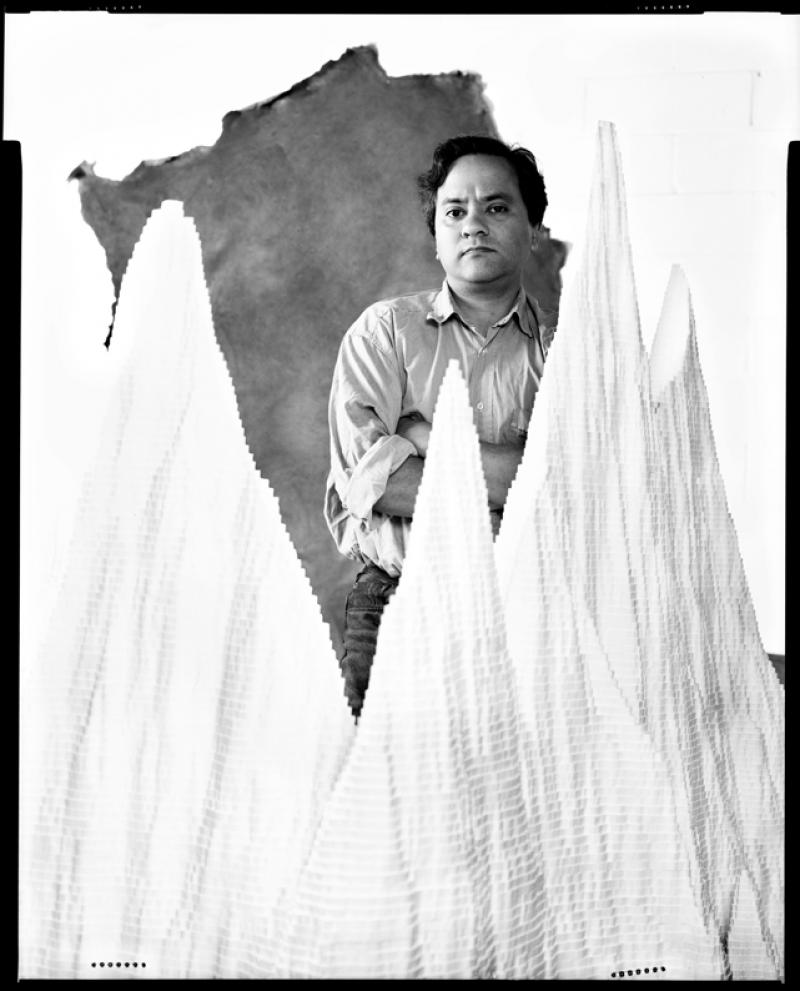

The sculptor Anish Kapoor (b. 1954), RA, CBE, won the Turner Prize in 1990. His public works are characterised by their gigantic scale and ambition. In the UK he is probably best known for Marsyas (2002), the viscerally red “ear trumpet” that elegantly spanned the entire length of the Turbine Hall in Tate Modern. He is also the artist behind the world’s most expensive public sculpture.

Closer to home, Kapoor is currently working on the world’s largest commission: a £15m five-part suite known as Tees Valley Giants, to be unveiled in five towns in the North-East. One, known as Temenos, will be an audacious 50 metres high and 110 metres long.

Closer to home, Kapoor is currently working on the world’s largest commission: a £15m five-part suite known as Tees Valley Giants, to be unveiled in five towns in the North-East. One, known as Temenos, will be an audacious 50 metres high and 110 metres long.

Kapoor’s current exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art offers a selective survey of his career, taking us from the pure pigment works of the early 1980s through to some newly created pieces, such as Tall Tree and the Eye located in the RA’s courtyard, a 15-metre tower of shiny steel baubles that resembles a cluster of helium balloons. Another new work is the sombre, monumental Svayambh (2007, picture below), its name taken from a Sanskrit word that roughly translates as “auto-generated”. As the 40-ton mass of red-coloured wax slides, almost imperceptibly, on sunken rails through the door frames linking five gallery rooms, layers are skimmed off like strata of raw skin. Shooting into the Corner, by contrast, is a loud, strutting work that features a cannon shooting 10kg of red wax every 20 minutes and splattering its visceral load on to a wall in an adjoining room. The work suggests a kind of comic anxiety about maleness.

Kapoor has now become the only living artist in the RA’s history to show in all of its galleries. Henry Moore enjoyed a comparable accolade in 1988, but by then he had already been dead two years.

FISUN GÜNER: It must be wonderful to be the venerated artist in the spirit of Henry Moore. Can you feel his spirit?

FISUN GÜNER: It must be wonderful to be the venerated artist in the spirit of Henry Moore. Can you feel his spirit?

ANISH KAPOOR: [laughs] Don’t know about feeling his spirit. But this is an incredible institution and it is a great honour to be filling this space. And these have got to be some of the best rooms in the world, certainly in England. It’s a fantastic kind of privilege to be showing in these amazing rooms – they’re beautiful.

Did they present any difficulties?

They’re grand. They test the work; the work’s got to be able to stand up to them. I don’t think you can get away with a half-good work here – it’s got to be bloody good or you’re not going to get away with it. There’s just something about these rooms.

Is it their history?

No, no, I don’t think it’s the history. I think it’s the light, the space, the volume, the sequence. All that. Well, you’ve got the high ceilings and you need that. Yeah, it’s got all of that.

One of the catalogue essays places you finally in the context of being an Indian artist. Do you feel more comfortable with that now?

Than I used to? Um, it’s just irrelevant. OK, not irrelevant, it’s a slightly relevant fact of my history. I don’t know what else I can do with it. It’s a fact of my history, that’s where I grew up, that’s where I am, I’m Indian. Yeah.

But when people get older, not just artists, but when people get older they do connect with their childhoods, their pasts more. They suddenly see relevancies that they didn’t see in their twenties.

Perhaps, yes, I’m sure that’s true. But I think, you know, it’s a fact of my life, and that’s fine. I’m sure many of us have got these, I’d say, rather exciting cosmopolitan histories that give us a view on the world that’s perhaps different, that places a different emphasis on things. But I’ve always been very concerned either not to make “Indian” art or not to be caught in a little circuit that says there’s this Indian view of the universe. I think somehow that being an artist is more problematic than that. But I mean, I don’t want to be described as a British artist. I mean, horror. I don’t want to be described, equally, as an Indian artist, which is equally a horror. Or anything else. Because what each one of those things does is to somehow tie up the possibilities. What I’m saying is, actually, there’s an intellectual, poetic history out there and one ought to be able to engage just as fully with Rilke, who happens to be my favourite poet as with, I don’t know, Mahatma Gandhi’s autobiography, which is also an extraordinary document of the way that one’s life, one’s clothes, one’s food and everything else can be political. One can go in any of these directions. And one wants to leave all these directions open and not say the incidents of one’s psycho-biography are the rules by which one is defined. So it’s obviously a very complicated question.

Yes, of course, but when you came on to the art scene people were obsessed with identity politics and multiculturalism.

Not when I came on to the art scene, because I came on to the art scene in the early Seventies and then there wasn’t any such thing. But in the last sort of 10 years, let’s say, there’s been a lot of that, good and bad. I mean, sometimes it’s actually rather good, because what it brings – on a more popular level – is a kind of acceptance, an acceptance that there are these other ways of seeing the world, that there are these cultural quantities that give us a measure of what we might be or how we might think about such-and-such an issue. But there are certain things that are very clear: I’m obsessed with red. One way one might think about that is to say, “Why is he obsessed with red?” and answer that, well, red plays a potent role in Indian culture. I mean, we could look at it like that, of course. And what that might do is inform some of the debate, but also narrow the debate, because actually red is also something that is just as potent in China or, I don’t know, for the Aborigines in Australia.

In all cultures, surely, because it’s a visceral colour. [Image below: Yellow (1999) and As If to Celebrate I Discovered a Mountain Blooming with Red Flowers (1981)]

Precisely. That’s where I’d rather go. I’d rather go with the idea that, actually, this is the stuff you’ll find inside our bodies, but, of course, informed by the fact that, I don’t know, brides in India wear red, or Aboriginal drawings are done with a kind of red ochre, or whatever. So I don’t mean to impersonalise the conversation, I just mean to say is that it’s more complicated.

Precisely. That’s where I’d rather go. I’d rather go with the idea that, actually, this is the stuff you’ll find inside our bodies, but, of course, informed by the fact that, I don’t know, brides in India wear red, or Aboriginal drawings are done with a kind of red ochre, or whatever. So I don’t mean to impersonalise the conversation, I just mean to say is that it’s more complicated.

You use the word symbolic quite a lot when describing your work. Do you mean in some Jungian sense? I could mention the tension of opposites in your work: the anima and the animus, the female and the male energies.

Not necessarily. I have been quite interested in - but a good many years ago now - all of that stuff. But we live in a world of night and day, good and bad, and opposite things, so why not a few opposites? [Laughs]

You’re in a very light-hearted, mischievous mood today. Have Jung and psychoanalytic theory informed your work in the way that it's informed, say, Pollock, and all those "heroic" American artists of the Forties and Fifties?

OK, that’s a serious question and I’ll try and answer it seriously. In a sense what one’s after as an artist is a way into a potent language. It’s an internal language at some level, and all the means that are available for that are to be used, or to be worked with. In a post-Freudian world psychoanalytic language, with its Jungian, Freudian, Lacanian or whatever else symbols, it’s one of those tools which is used to open up the inner, deeper meaning of things, whatever that is. And I think that, in a way, it’s my duty as an artist, my job as an artist, to do that. That’s what I’ve got to do.

You’ve done a great deal of psychoanalysis in your time. Did it inform your work?

I didn’t go into psychoanalysis in order to be an artist. I went into psychoanalysis to deal with some pretty real things. And then I saw that its language and my language, somewhere along the line, had a lot in common and that it could be extremely helpful. So, you know, it’s one of the things I go back to as an analytical method, and it’s a very useful analytical method.

Can I ask whether the therapist was female? (pictured above, Hive, 2009)

Why?

I’m just interested, because you stopped just before you married and the psychoanalytic relationship is very much a coupling - it’s a relationship. [Kapoor married the art historian Suzanne Spicale, with whom he has two sons, in 1995, after 16 years of intensive psychoanalysis.]

In a way it is, but no, actually.

Ah, she was a he.

Well, that blows your theory. I like it. Actually, I didn’t stop when I got married.

So was it an interesting experience?

Psychoanalysis? Er, I wouldn’t quite put it like that. It was bloody hard work. It’s the hardest work I’ve ever done in my life. Yes, it’s definitely the hardest work I’ve ever done. Because I think to really, really go deeply into… well, it’s hard work.

Discomforting? Embarrassing, shaming, maybe?

Yes, yes. All of that, all of that. And revealing. And somewhere one has to kind of, you know, face up to it, whatever it is. I think that in a way it’s a kind of meditation on the conditions of what one is. It’s a great luxury actually. Talking for a whole hour.

Did you feel that a great burden had been lifted afterwards?

Yeah, I did, but, you know, I don’t want to talk about this too much.

Sorry. OK, I asked about the word "symbolic" earlier. What does the word "spiritual" mean to you. Because that’s another word that attaches itself to you like gum.

I know. God knows. But again it’s kind of complicated. What’s complicated about it is this: first of all, you can’t set out to make something “spiritual”. You just can’t. I mean, what are you going to do? What is this thing?

There are shorthand ways of suggesting the spiritual in art, aren’t there?

No, no, I don’t think you can set out to do it. In fact, I know you can’t set out to do it. What you can do, however, is… It’s like beauty. Can you set out to make something beautiful? Do you know how?

I’m not an artist but yes, we have a notion of beauty. We understand beauty. We appreciate beauty.

Like the sort of guys who make those cars [points out of the window], and they’re bloody ugly. You know what I mean, though? We have these notions of beauty, but everything gets in the way. So beauty is another one of those things that’s elusive. You can’t set out to make it. But what you can do? And this is the point that I’m trying to raise also about the so-called “spiritual”, is to recognise that in a certain condition of matter, whatever it is, there is the possibility, there is the idea. I mean we could be talking about anxiety, for example. Could you imagine making something that’s “anxious”? Again we have only a notion. It took Francis Bacon a whole bloody lifetime, and he fought with it. He fought with the idea of how that thing can come to be.

His work couldn’t help but be anxious, because it was an expression of himself.

No, I don’t believe that. Not true. I think that’s completely not true. I think it’s the other way round. It’s a real struggle to kind of get there, to recognise that it’s possible. It is, if you like, a condition of being, but it’s getting it all there on a canvas – after all, it’s just paint. And that struggle is at least one of the struggles of the artist. Similarly, one might be talking about beauty or about the so-called spiritual. And they’re all nebulous and abstract conditions that in the right context – it has something to do with context – and in the right material form can come alive. And it’s the coming alive that is the poetry of the moment, the thing that matters. Sorry, if that’s too high-falutin', but that’s how it works.

You always seem to reject the notion of biography in work, but surely we can’t help but express ourselves through our work.

But I think it’s all a matter of emphasis, really. Let’s contrast Francis Bacon with an artist I admire much, much more, Donald Judd, who made boxes for most of his life. Well, psycho-biographical they may well be. Or they may not be. And I don’t think it matters. It’s all a matter of emphasis.

Picasso said that "style is death" to an artist.

And he’s right.

And your work has changed and evolved quite a lot, hasn’t it?

I’m an artist who believes in the studio. The studio’s really important for me. I spend a lot of my time in the studio and it isn’t just a place to make stuff, it’s really a place to experiment, to play, have a bit of fun in, to try something else out. To try and say, "Can I see the world like this or is it is possible to make art like that?" So that’s always been a very important part of my process.

Does being seen to have a signature style something you lose sleep about? (Pictured above, Marsyas, 2002)

On one level I don’t think about it at all. On one level it’s there. I know there’s such a thing as my, so to speak, “voice”. I know it’s recognisable. Even in works that are apparently not of the genre, you’ll still recognise it. So that doesn’t bother me at all, frankly. Much more difficult is the problem of somehow understanding how to remain playful and how to not get caught in the problem of just because I made it like that yesterday then I’m going to make it like that today. One has to be mentally - let’s say, poetically - agile.

You’re a very confident artist, aren’t you?

Well, on one level I know what I’m doing. I mean, I’ve been doing this for 35, 40 years, or whatever it is. That long? Well, long enough. I think I know what I’m doing. I mean I don’t always make great work. Nobody does. But as a kind of overall, broad thing, I do know what I’m doing. I don’t say that with a kind of arrogance. I just say that because it’s true.

You’ve said in an interview that artists don’t make objects, artists make mythologies. Two things occurred to me: that, no, actually, it’s we, the cultural observers, who make mythologies, and that it’s the artists who make the objects. The second thing is that it’s a very anti-minimalist statement.

The second one is true. But only to a certain extent is it true, because part of what we do as artists is this question of recognition: how is it that you come to know that the work is by a certain artist? How can one recognise its signature, if you like? Part of that is that we recognise a way of configuring things. When I used the word "mythological" I’m talking about that sense that somehow what you’re looking at is not just the object – you’re looking at the whole mythos.

Do you think it’s possible for an artist to have too much psychoanalysis?

[Giggles] I’m sure you can have too much of anything.

It hasn’t happened to you, but do you think there was a danger of remaining in a kind of stasis?

I’m not sure if that’s the danger. The danger is that – and it can happen to any one of us, from all walks of life, but especially in art – there is a moment when the work comes to be about such and such and such and such. And I’m not really interested in that. I want it to be about that today and we can go deeply there if we can, and maybe do it like that for the next however many years, but then we go over there, to somewhere else. And they may relate to each other, but it’s not linear.

You have a very mercurial, playful nature, which comes across in the work. (Pictured above, Shooting into the Corner, 2008-9)

Well, it’s not mercurial so much as that what we do as artists is not to say, “I have this story to tell and I’m going to tell it to you." My job as an artist is go to the studio and allow something to occur that is to me as surprising as I hope it will be to others.

As your work has increased in size you seem to have become less interested in visual deception and illusion. You seem to have moved away from that.

Have I? I don’t know. But have they become grander? They’ve sometimes become bigger. I hope they don’t stop being playful because that would be boring. Playful is where it’s at, I think. Grander? I must be more confident, if that’s the case. And scale? I mean, scale is a tool of sculpture. I’m not shy about it, because sculpture is all about scale. It’s about that sense that a thing is either bigger than you or smaller than you or in a particular relation to you, and it’s out of that that meaning arises. Without that in sculpture, there is no meaning.

Your works, like you, are quite slippery, aren’t they? Do you mind if I ask what your star sign is?

I’m a Piscean and a rather typical one - wriggly and elusive.

Were you disappointed not to get Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth [Antony Gormley got it instead, with One & Other]?

Oh, what do I feel? What do I really feel?

Well, you must have been pissed off.

No, actually, it was fine. What I really feel is that my heart was never truly in it.

Why? It’s a prime spot.

I don’t know. I think I’ve got a problem with plinths, generally speaking [laughs]. I’m a believer in sculpture on the floor, on the ground.

Anish Kapoor continues at the Royal Academy of Arts until 11 December. Book online here. A version of this interview first appeared in The Lady.

Watch a video about the making of Marsyas

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment