theartsdesk Q&A: Tenor Stuart Skelton | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Tenor Stuart Skelton

theartsdesk Q&A: Tenor Stuart Skelton

The Heldentenor talks Tristan, technique, and what it takes to be a great opera singer

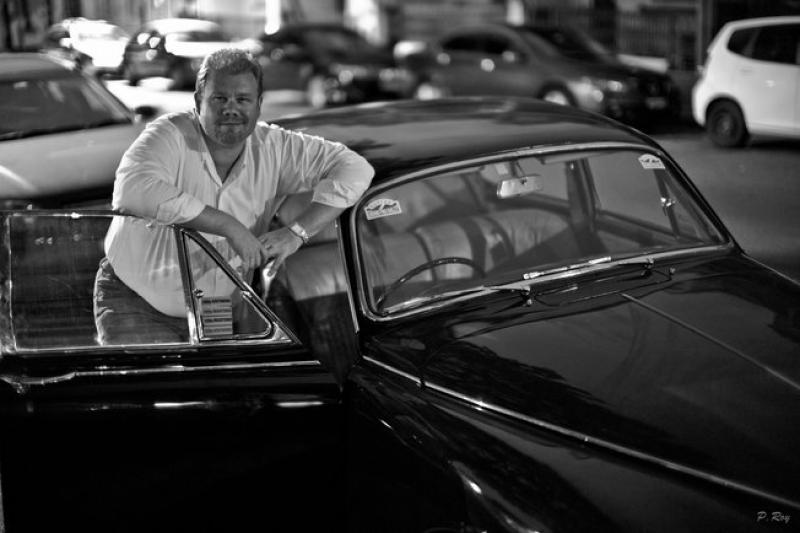

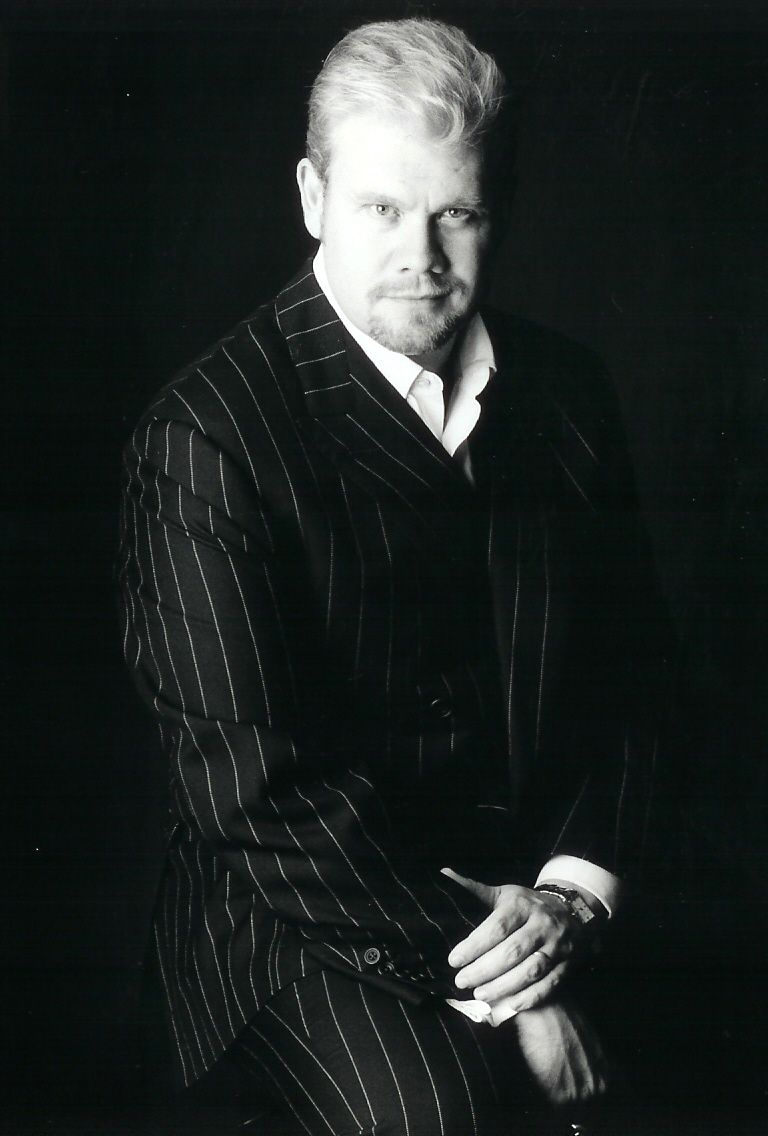

Described variously in the press as "virile", an "Aryan hunk" and a "great blond bear" of a man, Stuart Skelton may be the physical embodiment of machismo, but there's nothing of the beefcake about his singing. A Heldentenor of rare beauty and lyricism, Skelton's rise to operatic fame may have come young, but his is a voice and a career that looks set to stay the course.

Skelton has come a long way since his singing career started at age eight, as a treble in St Andrew's Cathedral Choir, Sydney. His journey from the music of the Anglican choral tradition to international success in the big Wagner roles has taken him far from Australia, to study in America and to learn the business in Germany's opera houses. Now a frequent visitor to English National Opera (the company that's as closest as he gets to "home"), we've seen Skelton as an innocent and heroic Parsifal, a passionate Eric in The Flying Dutchman and most memorably as the man-child Peter Grimes in the critically lauded David Alden production of Britten's classic opera.

Skelton returns this summer, along with many of the original cast, to reprise his role in a concert performance at the BBC Proms, but before donning his fisherman's jumper once again he finds time to talk to theartsdesk about Tristan, vocal tone, and exactly what it takes to be a great opera singer.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: You grew up among the music of the Anglican choral tradition as a treble at St Andrew's Cathedral School in Sydney, but have obviously gone on to work in rather different repertoire. When was your first encounter with Wagner as a listener?

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: You grew up among the music of the Anglican choral tradition as a treble at St Andrew's Cathedral School in Sydney, but have obviously gone on to work in rather different repertoire. When was your first encounter with Wagner as a listener?

STUART SKELTON: My very first encounter with Wagner was probably as late as 1993. I was singing one of the apprentices in the Australian Opera production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, and that was my introduction. I heard Wagner for the first time because I was required to sing it.

What did you make of it?

There was something about it even then. I’m not sure I really knew what that something was, but there’s a monumental element to it. It resonated with me, even if I didn’t really stop to analyse exactly why at the time. It just got under my skin.

You’ve expressed your reservations about Janáček before. Aside from him, is the repertoire you sing the music that really excites you, or given a choice would you rather be doing Donizetti or Handel?

If this wasn’t what I was singing, it’s what I’d be listening to anyway. I think there’s an emotional maturity to late-Romantic music – Strauss, Mahler, Wagner – that strikes a chord for me. Unlike the French or Italian grand opera traditions it’s not just about having pages and pages of beautifully spun line. It only works together with the words. I know people debate this, but for me you really can’t take a composer’s commitment to the libretto seriously if he can spend a page and a half on one word! Which isn’t to say that it’s not fabulous repertoire to listen to when well sung.

So have you always found the dramatic side of things as stimulating as the musical?

Yes – I’d much rather go and see a performance that is dramatically galvanising, that draws you in, even if it might not be perfect vocally, than go and hear something vocally perfect but that is somehow detached from the story.

Did the acting side of things come naturally to you, or was there a moment when you really had to commit and struggle to get that working?

I still have to work at it! The difficulty is that I’m still not entirely convinced that I’m very good at that part of it. But I look for the ways to best negotiate the drama, and I’m fortunate that in most of the repertoire that I sing the librettist and the composer were either one and the same, or they worked so incredibly closely together that you really only have to pay attention to what they give you on the page to work out how best to deliver that message dramatically.

I still have to work at it! The difficulty is that I’m still not entirely convinced that I’m very good at that part of it. But I look for the ways to best negotiate the drama, and I’m fortunate that in most of the repertoire that I sing the librettist and the composer were either one and the same, or they worked so incredibly closely together that you really only have to pay attention to what they give you on the page to work out how best to deliver that message dramatically.

On stage you seem so natural – it’s hard to believe it’s a struggle. Is this down to the directors you’ve worked with?

I’ve been very lucky on a number of occasions to work with directors who have done or said something that has really hit home for me, that’s been able to pull performances out of me that otherwise I don’t think I’d have been capable of delivering. (Skelton, pictured left, as The Prince in Rusalka.) In the rehearsal room you try and follow your instincts as much as you can, and obviously the really good directors see that, and if it’s a good instinct they encourage it and persuade you to invest it in. When you’re rehearsing as a singer you’re always second-guessing; good directors see that and can persuade you to follow a thought that you might feel was silly or wrong to its natural conclusion. That way you are always completely invested in what you are doing; your gestures are always coming from a place that isn’t artificial.

Are there particular directors who have changed a role for you, or your way of thinking about a character?

Absolutely. It’s great to be able to come to a new production of an opera you’ve done before because there are always some things from the last production that really clicked that you bring with you. However, that can also lead to slightly complacent or lazy performances, when you’re relying on some nugget from a previous production to bring things to life again and again. I think new directors, productions and colleagues can’t help but inform the way you perform, and change your way of thinking about an opera or a character.

I’m always happy to work with a director who can find your boundaries and then get you to walk past them a little bit

Have there been particular productions of directors that have forced you to throw everything you knew out and start from scratch?

I think the most extreme experience of that for me was the first time I worked with David Alden in a 2006 production of Jenůfa. I’d never worked with David, so I really had no idea what to expect. Up to that point most of my work had been in Germany, either in revivals where we really weren’t given much rehearsal time at all, or in new German productions where everyone would sit around a table and have interminably long discussions about concept.

David really challenged me as a performer; we've worked together a lot now, and in every production, without fail, we do the same dance. During the first week of rehearsals he asks me to do things he knows I will say no to, and during that first week I say no to everything he asks me to do. By the end of the week the two of us have both worked out where our boundaries are, and we have a terrific time and the performances always seem to convince audiences. I’m always happy to work with a director who can find your boundaries and then get you to walk past them a little bit, to test how far past them you are prepared to go. David always manages to find a way to make a part convincing to you as a performer, which in turn translates to the audience.

That conviction is something that really came across in Alden’s Peter Grimes.Where did you locate the sympathy in the character of Peter, who can be quite a challenge emotionally?

I think it’s easy to find the sympathy in a character, even one like Grimes (Skelton, pictured right as Grimes), if you just listen to what Benjamin Britten gives him musically. When Britten wants a character to be sympathetic that’s how he writes it; all you have to do is sing what he wrote and it works. You get a real sense of that with characters that he doesn’t want to be likeable – you’d struggle to make them appealing. It doesn’t always happen like that, but with this particular role and that particular opera, if you are fastidious with the score and the libretto, it’s very hard to go wrong.

I think it’s easy to find the sympathy in a character, even one like Grimes (Skelton, pictured right as Grimes), if you just listen to what Benjamin Britten gives him musically. When Britten wants a character to be sympathetic that’s how he writes it; all you have to do is sing what he wrote and it works. You get a real sense of that with characters that he doesn’t want to be likeable – you’d struggle to make them appealing. It doesn’t always happen like that, but with this particular role and that particular opera, if you are fastidious with the score and the libretto, it’s very hard to go wrong.

Which in theory should make it a perfect fit for a concert performance at this year’s Proms?

Absolutely. I think it makes such a strong concert piece, because the drama and the music are one and the same. That was certainly what we took great pains to bring out in the 2009 production. If you are doing justice to the music of Peter Grimes as a performer then you are also conveying the full weight of the drama to the audience.

Has anything consciously been changed for this concert performance?

My guess is that we won’t be doing nearly as much physically – there was lots of hanging off the ends of things and climbing of ladders.

You are so different to Pears, the singer so central to Britten’s conception of the role. Do you find that liberating?

Yes. One of the advantages I have is that I’m never, ever going to draw comparisons to Pears. The disadvantage is that on occasion – for good and ill – I have drawn comparison to Jon Vickers. He casts a really long shadow over the role, and obviously being compared to him favourably is a big compliment, but also a huge responsibility. If you look at the history of the role – Pears, Vickers, Rolfe Johnson and Langridge – all are completely different singers temperamentally and vocally, but each gave stunning performances that were completely valid. I think the great thing about this particular role is that any singer who takes it on, providing they understand and can master the vocal challenges of the role, can make it their own if they choose to. There is always something to be made of it that no one has done before. That’s the beauty of it; although there are these towering performances that echo in people’s memories, nobody comes away from performance thinking that just because it wasn’t like the Vickers performance it wasn’t any good.

Singing Britten is a million miles away from Wagner. Does it sit comfortably in your voice?

Yes, it really is incredibly comfortable for me (Skelton pictured as Grimes, left). But it’s not as much of a shift from Wagner and Strauss as you might think. There’s always a vestigial thought process about Wagner that you have to sing it all with as much power as you can muster all the time. Yet if you consider that when Wagner’s operas were being premiered there was no such thing as a Heldentenor – the concept just didn’t exist. So the people who were singing Wagnerian repertoire for Wagner, when they weren’t singing Lohengrin and Tannhäuser, were singing Arnold in Guillaume Tell.

Yes, it really is incredibly comfortable for me (Skelton pictured as Grimes, left). But it’s not as much of a shift from Wagner and Strauss as you might think. There’s always a vestigial thought process about Wagner that you have to sing it all with as much power as you can muster all the time. Yet if you consider that when Wagner’s operas were being premiered there was no such thing as a Heldentenor – the concept just didn’t exist. So the people who were singing Wagnerian repertoire for Wagner, when they weren’t singing Lohengrin and Tannhäuser, were singing Arnold in Guillaume Tell.

The act of singing Wagner has acquired this slightly mythic quality, but you don’t do him or the operas any disservice if you just sing them beautifully. When you get to the last half of the Ring Cycle there’s a certain change in philosophy, when voices become part of the texture rather than sitting on top of it, but I think even then there’s a lyricism to Wagner that has been mistakenly neglected. I think there’s such lyricism and beauty in the vocal writing that the difference of approach between Britten and Wagner isn’t as great as people might think. You can only sing with your own voice, and each singer has to accommodate their weaknesses – the parts of the voice you are less confident or comfortable in – as best they can. I think that’s the secret to really good opera singing: making sure that the audience doesn’t hear the bits that you aren’t good at!

You’ve spoken about your lyrical approach to Wagner, and this lyricism is becoming something you’re particularly celebrated for. Was this a style you were conscious of cultivating?

It was something that was drummed into me during my studies in the States. Both my teachers took great pains to say, “Do everybody a favour: sing as beautifully as you can for as long as possible.” I think that’s really not a bad way to think about singing. The day will come when you take on Siegfried – there is something about that role that is responsible for taking a little bit of sheen off the voice. Those who didn’t sing it – James King comes to mind – maintained the inherent beauty of their voice until they stopped singing. But those singers who did take Siegfried on didn’t become less impressive, their voices just changed. So if bringing beautiful vocal quality to your work is important then it might mean not doing Siegfried, or at least putting it off till the point where it really doesn’t matter anymore.

Is that what you’ve meant in the past when you’ve said that you are “wary” of Siegfried?

Yes, that’s definitely what I meant. That, and the role is as close to unsingable as anything ever written!

You’ve stepped in for a lot of other singers at the last minute. While so many Heldentenors seem to be fragile, your voice seems in excellent shape. How come?

I think it’s relatively well known that I don’t mind a cocktail and like a decent cigar on occasion, but never when I’m singing

I’m not aware of taking extraordinarily good care of myself; I think it’s relatively well known that I don’t mind a cocktail and like a decent cigar on occasion, but never when I’m singing. I have been sick, have sung sick, and it’s no fun. It’s mostly frustrating because there are things that you wanted to be able to do for the audience that you are just physically not capable of doing because your body won’t respond. You don’t have a full quiver.

You started singing Wagner comparatively young. Were you scared about the challenge for your voice, or just excited to be moving into this new repertoire?

I was excited. I had done Eric in 1999 in Strasbourg, which was a very gentle way to be introduced into the repertoire. But the very next thing I did was Lohengrin – just before my 30th birthday. The rehearsal process was very long, and I just forced myself to sing it every day in the studio. I didn’t see any point in leaving to chance whether or not I could actually get through it once we were on stage. So I sang it every day. I remember telling my colleagues that I was off to another Lohengrin coaching. They’d joke and ask, “Don’t you know it by now?” Of course I did, but I just wanted to make sure that once I was on stage with an orchestra and an audience that I could still do it.

Speaking of big-role debuts, you’re singing Herman in Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame for the first time later this year in Australia. Is it hard to debut a role in concert?

I actually think it’s a good way to start. It means you can concentrate just on the physical requirements of singing. (Skelton pictured as Parsifal, right.) You can monitor where your voice and your head are at constantly, which when you are performing on a full set you simply can’t. It’s not as exciting to do it in concert of course, but at least you can concentrate on just singing as well as possible.

I actually think it’s a good way to start. It means you can concentrate just on the physical requirements of singing. (Skelton pictured as Parsifal, right.) You can monitor where your voice and your head are at constantly, which when you are performing on a full set you simply can’t. It’s not as exciting to do it in concert of course, but at least you can concentrate on just singing as well as possible.

Rumour has it that you also have your first Tristan coming up in 2016…

I can’t confirm yet if or where that will be happening, but it’s a prospect that’s really, really exciting. And at this stage it looks as though all those serendipitous things that would need to come together for me to agree to do Tristan for the first time will be in place – director, conductor and wonderful colleagues.

Vocally was it something you knew you were ready for?

My agent and I always said we would know when it was the right time. So when this enquiry came through and it seemed to tick all the boxes, we just felt that it was right. My decision was also prompted by a discussion that I had with Ben Heppner. We were talking about Tristan and he offered me two pieces of advice. The first one was not to do it too early – that’s the advice everyone expects. But the second thing was something I really didn’t anticipate. He also told me not to leave it too long. When you first sing Tristan you want to be at your absolute peak and have every possible resource at your disposal. The longer you leave it the more the ageing process takes your resources away. Once you’ve done it once your body acclimatises and you can adjust more easily with your ageing process. That struck me as a really good piece of advice. I feel in great shape vocally now, and can’t imagine by 2016 I’ll feel any worse. So I think it will be time.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Add comment