Tabu | reviews, news & interviews

Tabu

Tabu

A wintry Lisbon tale spawns a magnificent idyll of illicit love in colonial Africa

A wondrous antidote to digital movies’ colonisation of the darkening continent of cinema, Miguel Gomes’s luminously black-and-white Tabu is a tripartite paean to the past: to the perils of Portuguese imperialism in Africa; to Hollywood silent movies as they transitioned to sound; to an adulterous affair that trapped its enraptured lovers for the remaining 50 years of their lives.

It’s also a picture with a few meta-movie tropes – a waterlogged camera lens, a home-movie shoot with a malfunctioning Bolex, an irrational sideways shot – that addresses the storytelling impulse and the undiminished craving for the kind of old-fashioned narratives that reflect the emotional needs neglected by most of the cynical, anaesthetizing, and over-determined films of today.

Silent in its second half but for ambient sounds and a voiceover narration, Tabu has one analogue in The Artist, though Gomez’s film is less sentimental and more demanding than Michael Hazanavicius’s crowd-pleasing Oscar-winner. It’s also analogous to Leos Carax’s digitally shot and comparatively loony Holy Motors, with which it shares an absurdist sense of humour and a longing for celluloid purity in the post-film era.

Silent in its second half but for ambient sounds and a voiceover narration, Tabu has one analogue in The Artist, though Gomez’s film is less sentimental and more demanding than Michael Hazanavicius’s crowd-pleasing Oscar-winner. It’s also analogous to Leos Carax’s digitally shot and comparatively loony Holy Motors, with which it shares an absurdist sense of humour and a longing for celluloid purity in the post-film era.

The German master FW Murnau structured his 1931 drama Tabu, a Story of the South Seas, made with the pioneering American documentarist Robert J Flaherty, in two parts: “Paradise” and “Paradise Lost.” More of a spiritual parent to Gomes’s film than a narrative influence, the first Tabu bequeathes these chapter headings to the new one, also a diptych. The difference is that Gomes starts with “A Lost Paradise,” a story, shot in 35mm, of three women in contemporary Lisbon, and follows it with “Paradise,” a colonists-in-Africa episode circa 1960, shot in grainy 16mm, that evokes the Earl of Erroll murder case depicted in 1987's White Mischief.

There is also a wittily stilted prologue set in the African grasslands where an intrepid Victorian explorer (Telmo Churro, above right), unable to cope with the death of his beloved wife, commits suicide in the jaws of a crocodile. Before he dies, his wife’s ghost tells him that he will not escape his heart, a warning for the second chapter’s ill-starred lovers.

The protagonist of “A Lost Paradise” is the unmarried, middle-aged human-rights activist Pilar (Teresa Madruga). She cannot return the feelings of the male artist friend who loves her and has been upset by the decision of a young female Polish religious student not to stay with her. She is most troubled by the strange behaviour of her elderly neighbour, Aurora (Laura Soveral), who has spent all of her allowance at a casino and is prey to paranoid delusions that her black maid, Santa (Isabella Cardoso), is practicing witchcraft against her. Gomes never explains why Aurora’s daughter, who lives abroad and sends instructions to Santa, either has no interest in her mother or hates her, but it’s deducible from the conduct of the thirtyish Aurora (Ana Moreira) in “Paradise.”

Set over a few days at Christmas and New Year, the Lisbon section is wintry and depressing. It is thus illustrative of Pilar’s existential crisis (which her prayers do little to alleviate), Aurora’s decline into dementia, and the sombre presence of Santa, an advocate of tough love. Her taciturnity – she barely acknowledges the birthday cake Pilar brings her – is also indicative of the resentment she feels toward her inferior station, a residue of the colonial exploitation dealt with in the second part. Retrospectively, it becomes clear she is the film’s unsmiling conscience. She is there for Aurora, though, when the dying woman writes a name, VENTURA, on her palm with a finger.

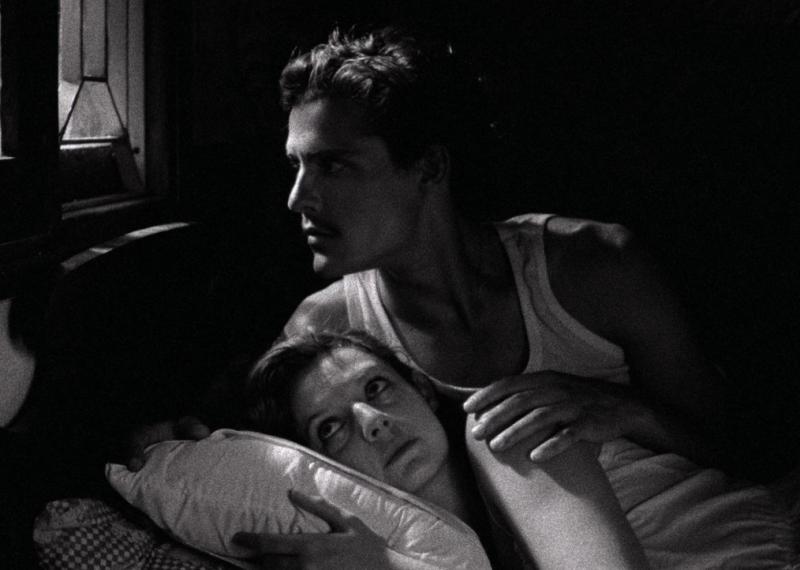

“Aurora had a farm in Africa at the foothill of Mount Tabu,” quietly announces Gian Luca Ventura (Espírito Santo), an aged, elegant Genoan gentleman (who has been institutionalized by his thuggish-looking son). Gian Luca’s words, delivered to Pilar and Santa when they take him for coffee after Aurora’s funeral, are as resonant as Joan Fontaine’s “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again” in Rebecca. It’s the start of his long, haunting narration over the exquisitely beautiful and dialogue-less images of “Paradise”’s extended flashback, which shows how, as a young rake (Carloto Cotta) who had fetched up in a Portuguese colony in Africa with a former seminarian friend who aspired to pop stardom, he embarked on a mutually adoring and sexually passionate affair with Aurora.

The beautiful young Aurora suggests an unstable, capricious, European Ava Gardner in 'Mogambo'

She and Gian Luca came together when he returned to her the escaped baby crocodile playfully given to Aurora by her husband; the beast perhaps carries the sense memory of the explorer eaten by one of its forebears or is even the explorer resurrected. As a pet, the baby croc is a symbol of colonial hubris and the tragedy that will inevitably result from the adultery. It would be giving away too much to say how the affair plays out, suffice to say that Aurora buries it in her memory, only to summon her old lover on her deathbed.

Filmed like a movie goddess by Gomes, the beautiful young Aurora suggests an unstable, capricious, European Ava Gardner in Mogambo: she’s the top woman big-game hunter – a movie-loathing consultant on the (fictitious) RKO flop It Will Never Snow Again Over Kilimanjaro no less! – who at the time she started sleeping with Gian Carlo was pregnant with her and her tea planter husband’s only child, the aforementioned daughter.

In the first scene following the prologue, the lonely Pilar is shown standing aimlessly in a screening room. She is a character in search of a movie. Just as Santa delights in Robinson Crusoe, Pilar receives Gian Luca’s narration of his and Aurora’s story as a benediction, for what she sees in her mind's eye as he talks is as stylized as a late silent or early talkie. Gomes depicts it as a blend of Flahertian ethnographic documentary, heightened romantic melodrama, and exotic adventure, along the lines of White Shadows in the South Seas (1928), Trader Horn (1931) or Red Dust (1932) – though one scene of Gian Luca and Aurora making love would have scandalized pre-Code audiences.

Thus the memories that Aurora couldn’t own up to, for shame, are filtered through Gian Luca’s memory and his regretful tale and transmogrified into a cinematic experience by Pilar, our anxious surrogate, who receives it as a myth that enables her to solve Aurora’s mystery and find some temporary peace. Watching the magnificent Tabu, we may feel we’re experiencing another kind of myth – the myth of cinema as resurgent ghost.

Watch the Tabu trailer

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Blu-ray: Two Way Stretch / Heavens Above!

'Peak Sellers': two gems from a great comic actor in his prime

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

Blu-ray: The Rebel / The Punch and Judy Man

Tony Hancock's two film outings, newly remastered

Blu-ray: The Rebel / The Punch and Judy Man

Tony Hancock's two film outings, newly remastered

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire review - a mysterious silence

A black Caribbean Surrealist rebel obliquely remembered

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire review - a mysterious silence

A black Caribbean Surrealist rebel obliquely remembered

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Add comment