Film Q&A Special: Only When I Dance | reviews, news & interviews

Film Q&A Special: Only When I Dance

Film Q&A Special: Only When I Dance

Interviews with the young star and director of an inspiring new documentary

There are gunshots outside in the street, a boy sits behind his front door desperate to get to ballet class, the two sides of his life colliding in front of his eyes - reality and dream. It’s a favela in Rio, one of the most dangerous cities in the world, a vast estate of poverty riddled with drug crime and addicted young lads with no future other than dealing, until they get shot or jailed. Ballet... well, what an irrelevance.

This is the background from which, unbelievably, a fairytale became real. A boy, Irlan da Silva, escaped his certain destiny and this year became a professional ballet dancer with the great American Ballet Theatre in New York - a fairytale, still more unbelievably, which is captured on film in a remarkable documentary film that goes on general release in the UK this week, Only When I Dance. This is no made-up Billy Elliot tale. This is the realest deal there could be.

Only When I Dance was begun as a hopeful documentary about social projects in Rio’s favelas, the aim being simply to show another side to the Brazilian image of violence and hopelessness, with kids achieving real things in their appallingly blighted neighbourhoods. Director Beadie Finzi and producer Giorgia Lo Savio could never have imagined just what they would end up filming.

Having decided that capoeira was overdone as a Brazilian theme, Beadie was drawn to the idea of ballet - she’d been told about a remarkable teacher, Mariza Estrella, who runs Rio’s Centro de Dança, where she gives free lessons to kids she talent-scouts in the favelas.

In her top two classes Beadie found two outstanding children: Irlan Santos da Silva, a boy set apart from all others by the intensity of his love of dance, his beautiful physique and his evidently unusual talent, and Isabela Coracy, who faced the biggest barrier possible in her dream of becoming a ballerina: she is black. Even out in the world there are few black classical ballerinas - in Brazil, there are none.

In the film, we see the two of them win chances to perform at competitions abroad, the heroic struggle of their destitute families to scrape together the fares and subsistence money, and their respective fates. As one rises and the other fails, the ambition of their dream takes full shape.

The odds against them are unemotionally spelt out: Mariza, their teacher, says sadly but realistically to Isabela (pictured right) that she will almost certainly never get a job in classical ballet in Brazil, because of her colour. Her only hope is to win a place in a foreign company. Yet Isabela’s physique is against her. Her friends (all whiter than she) tell her it isn’t about ass and thighs, but it is.

The odds against them are unemotionally spelt out: Mariza, their teacher, says sadly but realistically to Isabela (pictured right) that she will almost certainly never get a job in classical ballet in Brazil, because of her colour. Her only hope is to win a place in a foreign company. Yet Isabela’s physique is against her. Her friends (all whiter than she) tell her it isn’t about ass and thighs, but it is.

Meanwhile her working-class family are desperately selling everything, borrowing from any shark anywhere, to raise the $2,000 to enable this girl to chase her impossible dream. It's the kind of family solidarity you would not expect to find in comfortably off Western families: a solidarity where one child carries the life hopes of all their relatives.

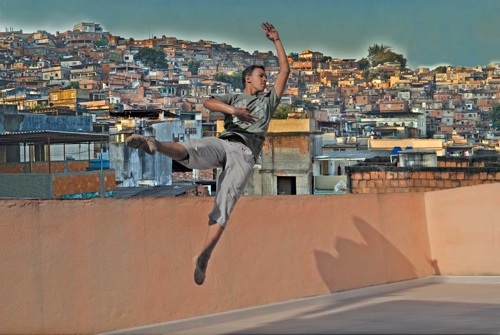

For Irlan, seen first in a glorious opening sequence exercising on his roof at sunrise, the odds are different. Boys are in short supply in ballet, and besides Irlan has a quiet inner confidence and self-discipline that his headmaster remarks on. But the school is chaotic, illiteracy the norm, and death is just outside the gate. He lives inside Complexo Do Alemão, a hellish slum city of 300,000 inhabitants without proper sanitation or infrastructure, and renowned as the "beating heart of Rio's drug trade", or even "The Gaza Strip of Brazil". You wonder how such a boy, so self-contained, proud and sensitive in taste, has survived this violent jungle. The steps up the escape ladder are grinding, tense, and one is often on the edge of one’s seat.

The film has the great merit of being a documentary, not a drama-doc, so the wonderfully improbable unfolding of events takes place not with sentimental washes of music but to the bangs and noise of the dance studio, or the street, or the kitchen. One thing that is downplayed is the violence of the favelas, which in the interview below Beadie Finzi talks about in detail. Yet as Irlan told theartsdesk in his interview, you only have to look at the fate of some of his classmates to see what the truth is.

Meanwhile, although on the film Isabela’s heartbreak must be felt by every viewer, in the aftermath there has been a torrent of good news, the latest in the last fortnight. Not only has the documentary itself garnered praise from film festivals worldwide - from Tribeca, Vancouver, Edinburgh, Seville, Sheffield, and Rio itself - both the kids both have reason to celebrate: Irlan is now a professional dancer at one of the world’s most famous companies, while Isabela has taken the first professional step towards becoming what her teacher said she could probably never be: Brazil’s first black classical ballerina.

Last week theartsdesk met Irlan, now 19, in London, and he talked (via an interpreter) about his extraordinary life so far.

There’d be gunshots in the street. It’s constant, every day. it’s a very difficult, scary life being in the middle of that

ISMENE BROWN: What did you imagine your life would be when you were young?

IRLAN DA SILVA: I never had much idea. I think I was lucky being shown the right path with ballet. The first time I saw ballet I fell in love with it - when I was 12 I saw a Mikhail Baryshnikov video of Don Quixote at ABT. He is my inspiration. I always loved dancing samba - so do my parents - but I had had no ballet contact until them. My mum now works in our café (picture below left), my father is a manager for a freight transport company. I suppose if I hadn't found ballet I would probably have gone on to further studies, because before I discovered dance I was a good student. It’s just that dance took over my life, and I didn’t have time for studies.

In the film you said when you were young your dream was to get away. What from?

From the favela, because life there is so difficult and so stressful. So many times I couldn’t go to rehearsals or see a performance, I was stuck at home because there were shoot-outs outside. Or I would be at a friend’s house and my parents would tell me to stay there, not come home. There’d be gunshots in the street. It’s constant, every day. it’s a very difficult, scary life being in the middle of that.

From the favela, because life there is so difficult and so stressful. So many times I couldn’t go to rehearsals or see a performance, I was stuck at home because there were shoot-outs outside. Or I would be at a friend’s house and my parents would tell me to stay there, not come home. There’d be gunshots in the street. It’s constant, every day. it’s a very difficult, scary life being in the middle of that.

Your father said on the film, if you didn’t dance, you’d end up dealing drugs and your life would be short. That’s the reality.

Yes. I have classmates who are now drug barons, or who have died because they got involved in drug traffic. Kids see it as an easy way out, money fast, but they don’t think of the consequences.

What did you think when these cameras arrived? These film-makers invading your life.

I was scared! Nothing like this ever happened to me. At first, I was confused, I asked myself why these girls were filming me the whole time. Sometimes they’d be filming and I was thinking, Enough! Go! But I could never have imagined it would turn into this.

Did it get you unwelcome attention in the street?

People would poke fun at me sometimes, say here comes the Star, but it was in good spirit. And I have had huge support from my mother, and also my father, even though at the beginning he was prejudiced against it (Penha and Irenildo pictured below right). And I was also really motivated by watching videos of dancers over and over, and realising from watching their moves that I could achieve these moves as well. So I would practise them again and again. It was like I was living within this bubble that is the world of dance, it protected me, it motivated me.

Where does your faith in yourself come from?

Both my parents are religious, Catholic, and they brought me up to be religious. My faith comes from God, I pray every day, and thank God for what I have been given. Maybe I have a lucky body too, because although I feel aches and pains - well, if you don’t feel those you’re not doing it right - I have never had a serious injury.

Both my parents are religious, Catholic, and they brought me up to be religious. My faith comes from God, I pray every day, and thank God for what I have been given. Maybe I have a lucky body too, because although I feel aches and pains - well, if you don’t feel those you’re not doing it right - I have never had a serious injury.

Has your background held you back or made you more determined?

It has made me stronger. I look at my parents. I was always given what I needed by them - despite difficulties they always put food on the table, gave me everything I needed to survive every day. That has given me a lot of strength.

What was it like to join ABT?

I did last year with ABT2 as my prize from the Prix de Lausanne, and now I am on a full contract with them. It was really scary, oh my God! I had so much to learn. Four new choreographies in my first week, and then straight out on tour. I have had to learn many, many, many things. I learned to rehearse in a short time and dance in a much longer span of time - in Brazil it was all rehearsing. Here it’s two weeks intensive rehearsal, then off to perform. In the entire time I was at school I danced less than I have here in a month. And you learn so much about ballet - we all take class together which is a great thing, a huge opportunity for me. To work alongside Marcelo Gomes, for instance - his quality of princeliness on stage, I want to develop this presence on stage that Marcelo has. Technically too Marcelo is very clean. And in London of course I met Thiago Soares from the Royal Ballet, who started in the same school as I did with Mariza. My dream is to become, as Thiago has, a major male star known throughout the world for ballet.

You are only 19 and you started ballet aged 12 - it is such a short time. It’s a fairytale, and it happened to you on film.

I can’t believe everything that happened to me. It is so fast. I am so incredibly happy.

BEADIE FINZI, 38, director (pictured below right): Giorgia Lo Savio, the producer, first came to me in 2005 and said I want to make a dance film in Brazil, maybe capoeira. I said, “Hmmm.” It seemed a bit obvious. But this was the start of a fantastic dialogue and research period. We started looking at social projects in the favelas to get kids off the street, and I gradually steered us towards ballet. Because what got me was the idea of young black poor kids in this suburb of Rio using ballet as a means to escape - quite extraordinary. There were a lot of ideas to explore, class, race, cultural clash, some very interesting ingredients.

Was it necessary to find “the right story”, “the right children”? Because time flies by with children, they change very fast.

Was it necessary to find “the right story”, “the right children”? Because time flies by with children, they change very fast.

Exactly. There was one young man we pursued for a while, but his parents didn’t understand why we wanted to film it and they were reluctant for us to get involved.

They didn’t support their son as much as you hoped?

I think that probably was a keen idea for me. But it's typical in documentaries that you take a while to find the right characters. It was when we came across the Centro de Dança and this extraordinary teacher Mariza Estrella that it clicked into place. She clearly had an eye - Thiago Soares [the Royal Ballet principal dancer] had come through her school, and we looked at her two top classes, and these kids who’d been beneficiaries of her free lessons scheme, Irlan and Isabela, stood out. Both fabulous characters, very charismatic, natural leaders, and yet also more than competent dancers, surprisingly so. This story was never going to work unless there was a chance that this would all come off. You can never know what will happen in an observational film, but there had to be a chance these kids had good enough raw talent to do something. That’s what I saw in them from the start, and made me say, let’s do it. This was the critical year when the kids had their first opportunity to be in an international competition and be scouted for a foreign company. This was make-or-break year for them.

But if they hadn’t got through each of these stages - if they hadn’t been selected for the Brazilian contingent to perform in New York’s Youth America Grand Prix, or Irlan hadn’t won a scholarship at the Prix de Lausanne - what would have happened to your film?

I was prepared for two very different outcomes - with observational films you never know what’s going to come at you, you have an idea, a theory of your narrative line, but it’s like surfing a wave, you had to be braced for anything. But in fact the story fell very well. Even Isabela’s sad outcome provided an important foil to Irlan. It would have been a very saccharine film if it was just about Irlan.

I felt watching it that this was an interesting choice of the two youngsters - Irlan had the odds probably stacked for him, because boys are in terrific demand, while Isabela (pictured left) had all the odds stacked against her, because she is black and a girl, in the most competitive arena of all.

I felt watching it that this was an interesting choice of the two youngsters - Irlan had the odds probably stacked for him, because boys are in terrific demand, while Isabela (pictured left) had all the odds stacked against her, because she is black and a girl, in the most competitive arena of all.

But with Isabela in fact we've just heard there have been great developments. You remember that ambiguous shot at the end of the film with her in the studio with a young black girl? I did this because I didn’t want to leave her on a miserable note. But actually within a few months she got a place with the Deborah Colker company, a contemporary company, which she liked, but it was not her number 1 passion, which is classical. And in fact just two weeks ago she won a place with São Paulo’s classical company, so she will be able to achieve her dream. Such wonderful news. And she proved Mariza wrong about there being no black classical ballerina in Brazil. Within Brazil she will be able to dance what she wants. What she’s overcome has been phenomenal, in fact.

This idea of such strict internal racial prejudice in Brazil is a surprise.

Yes, there are many many shades of race and colour within society in Brazil. It tends to be that the lighter you are the higher-caste you are. It is a very racial society, fullstop. This again I found fascinating. But listen, the difficulties for dancers of colour getting into classical ballet anywhere are well known - it’s not easy, that‘s not a secret - but Isabela’s situation was more exaggerated.

She also had genes stacked against her. She’s a graceful and charming girl, but her parents have very sturdy genes, and many major ballet schools look at the parents before they accept the child. I loved that last scene of yours where she was teaching the young girl.

That wasn’t contrived at all. Mariza very cleverly asked Isabela to support and help this little black girl just starting in her school. A stroke of genius because it started to rebuild Isabela’s self-esteem. And a year later, look what’s happened. I’m incredibly moved and proud of her. I could have danced for joy. It feels like the biggest battle of all has been won.

One of the fathers said in the film that if his boy didn’t dance, his destiny would be on the streets as a drug-dealer, with a short life. In your film you underplay the violence of the society - it’s referred to but not seen. Was that deliberate or was it actually hairy?

Yes, both things. It is a very hairy place to work. And I’m proud that we managed to work there for a year,the whole team, moving in and out of both places. But you know it’s very easy to come to Rio and become intoxicated by the violence. It’s heady, it’s everywhere, it’s in the papers every night. It’s shocking what is going on - these places are lawless, and very, very frightening indeed. I didn’t want to become distracted by that. I’d have ended up making a film like every other one about Rio's favelas. I felt one should just state it and get on with the story, the characters. If the violence impinged on our characters’ lives while I was filming of course I’d try to address it, but I didn’t want it to become the main theme, yet again.

What sort of things happened?

What sort of things happened?

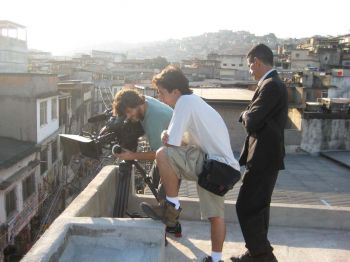

There was a daily drama of getting in and out of the environment. We spent a long time negotiating with a community leader to give us safe passage, he had to be bribed several times to keep that safe passage open for us in the favelas. And you’d be shooting somewhere on a roof, and you’d get a call saying, “Get down now, there are guys up in the hills watching you and they’re unhappy.” If you displeased them, there would be trouble.

What was the risk?

Well, kidnapping and murder are very commonplace. But as I say we worked very hard to make sure we didn’t overplay things, if they said, “Get out,” we got out. You have to play the rules. In the end, for Irlan, Penha and Irenildo that’s their home. I had a responsibility not to foul up their lives.

The proudest moment was a few weeks ago when we took the film to the Rio film festival, and before the gala screening we took it to the favela. We built a temporary cinema in the courtyard of the church in the Complexo Do Alemão, with a borrowed projector and screen, because I knew many of the community couldn’t come out downtown to see the gala screening, and we invited them to come see what the boy had done, because they had no idea. It was an incredibly emotional experience - people couldn’t believe what they were seeing, the parents were weeping, Irlan was crying, everyone was cheering. People couldn’t believe such a positive thing could come out of this place. That was a very important moment for everybody.

Did the parents have to accept their relationship with the community might be changed by having had you there?

That relationship of theirs with their community was very important. Being aware what the community felt about us. I mean, just to film Penha going down to the market to buy vegetables was a major drama. Very stressful to organise. I’d have people watching out for me on all the corners, are we okay, are we getting into trouble? It wasn’t worth making any trouble.

There was a lovely scene when his parents talked about how they met dancing, and held hands, and you shot them walking out into the night street to dance. Was that dangerous?

No, it was a public area. I mean, you had eyes in the back of your head watching what happened to your gear, but this was just a wonderful weekly market and dance about three-quarters of an hour away on various bus routes. That was their weekly passion to go down there, dance, have a few beers. Delightful.

What about the seeking of loans of Isabela’s family? We got a glimpse of a very rocky world that they were trying to raise $2,000 in.

Everybody in the family went out and got loans. Grandma got loans because she had some credit rating, but the dad had none, they borrowed, they sold things. I have to confess, at the end of filming we helped them too, because it was just too painful, they had become so overextended you couldn’t see how they would recover from that. It inspired us to set up a fund - on our website you can donate $10 or $20 to the Vida Fund to go direct to Mariza's school, to get shoes or kit for kids there, competition fees. That’s been a wonderful thing to do. It won’t solve all the problems but it'll provide a running fund for Mariza to call on with families like this.

Which scenes struck you in particular that you saw out there?

The very opening scene with Irlan dancing on the roof top. I dreamed that scene a year and a half before I filmed it, because he’d go up there to warm up. There was something about that statement of him dancing on that rooftop with the favela tumbling away beneath him. It was also where the title of the film came from, he said it was only when he danced that he felt free. And that was a scene I found very emotional to shoot, because I’d talked about it so much, visualised it so many times.

The other scene was when he danced the Neumeier Nijinsky piece in the Prix de Lausanne competition. I was dead against him dancing that piece - I thought it was a terrible mistake, I hadn’t seen in rehearsals that he’d have the emotional maturity to pull it off, and there were simpler pieces that showed his great jumping and leaping - and I was proved entirely wrong. He took a risk and really pulled it off. My heart was in my mouth, shooting it from the wings, and everybody felt it was an exceptional performance, everybody in the theatre.

One striking thing was how you shot the whole solo with a fixed one-shot.

It was unbelievably worrying. We were very restricted, of course, because it was a live performance. We had a motley crew, my camera assistant I put in front with that full wide camera and I was in the wings, and I was rather distraught that we hadn’t enough money for more cameras and I’d have so little control over this key moment. It was unbelievably pressured.

But in fact it is great as a viewer to have such concentrated communication with his face and admire the symmetry of his body. To me it brought his intensity to the fore and totally rescued that choreography.

I couldn’t agree with you more. I came back to the edit suite and was almost ashamed to tell my editor all I had was this camera shot. Then as I looked at it, we started trying with lots of cutting, but then said, no, just watch this boy. This angle. It’s just what you’re saying.

Another lucky thing was having your camera rolling when he saw snow for the first time! Some scenes I found astounding, such as the chaotic scenes inside his school. The headmaster who said Irlan's life was run by a stopwatch, and he had no friends, because he had no time to listen or to talk. I wondered how Irlan had stayed alive, actually. He doesn’t look like the kind of boy who can lay people out with a punch. How has he survived, with his esoteric interests?

This was a painful insight. You felt more there than anywhere else what a loner he was, how alone his life was. Irlan was already in totally another place and wanted so much to be away. His father was really shocked when he first told him he wanted to do ballet, and there was real trouble between them for a long time. But then a reconciliation happened, and now Irenildo is his son’s greatest fan, the most loving and supportive of fathers. My understanding is that when people first started finding out Irlan was dancing ballet he did get a lot of stick, and the legend is that when it went too far Irlan did throw a punch. Now, I didn’t see any evidence at all in the favela of bullying or spite towards him, and I think I would have done if it existed. We were in there so much. So I’m happy to think that they did in their own way accept him, and now they have come forward to say how impressed they are by what he did.

What now for the film?

It goes on general release now, which is a fairytale ending to a wonderful year on the international festival circuit. We’ve played at Tribeca, Edinburgh, Vancouver, Rio, Seville, Sheffield... all sorts of places. It’s done greater even than I’d hoped, and to have a theatrical release in the UK is a real privilege for a little Brazilian dance doc.

Jan Younghusband’s involvement means Channel 4 transmission?

Yes, it was one of the last things she commissioned as Head of Arts at Channel 4 so I think it’ll be broadcast at the end of the year.

In your own career how does this film fit?

I’m not any dance specialist but I get a real pleasure from shooting and cutting movement and dance. I’m very consumed with how we communicate this kind of art form to a mass audience - that’s a big thing for me, to take ballet or modern dance that most people say they couldn’t imagine understanding or liking, but lacing it through a story and taking them by surprise. So maybe they’ll take the risk of buying a ticket for a performance.

Did you in the end work out what this magical trap was that ballet offered to those kids? Did you understand the lure?

I’m not sure I do. I think the reasons are different for the two. For Irlan it’s a physical exaltation in the leaps and bounds of ballet. With Isabela, though she’s a very competent contemporary dancer, her obsession with ballet I think for her was much more bound up with the vision of the ballerina. It was displayed in the things she kept in her room - the look, feel, image of the ballerina, I think that lured her.

- Only When I Dance (Tigerlily Films) is released this Friday. It is showing at the Barbican Cinema, London, 4-10 December; other venues tbc here. Film website

Watch the trailer below:

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Add comment