Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Novello Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Novello Theatre

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Novello Theatre

James Earl Jones makes a career-best Big Daddy

The voice has landed, and what an astonishing sound it makes.

Allen's New York account of this same play did knockout business but got sniffy reviews a season or two ago, where discussion at the time centered around the supposed distaste of film star Terrence Howard, making his stage debut as Brick, for the rigours of a Broadway run. In London, Howard and his Broadway leading lady, Anika Noni Rose, have given way to Adrian Lester and Sanaa Lathan, both of whom acquit themselves more than creditably as the alcoholic, "click"-happy Brick and his curvaceous, child-hungry wife, the febrile Maggie: Williams's eponymous "cat".

But deftly though she powers through the opening act - in essence, an extended monologue punctuated by interruptions - Lathan is in essence priming us for the main course that arrives after the interval. That comes with first the unmistakable sound, and then sight, of the physically capacious James as the cancer-ridden patriarch who won't go gently into the good night. Exulting in a reported reprieve from "death's country" that Big Daddy will later discover is a lie, the actor sends the production hurtling into life and toward a third act from which he then, alas, is mostly absent, at which point Phylicia Rashad's tremulous Big Mama brings the evening home.

I've always thought Williams's most outsized male character was one of those supporting roles whereby you can't go wrong, rather like Mercutio, say, or Ibsen's Judge Brack (a part I once saw Jones do). But even by comparison to such previous, and formidable, Big Daddys of my experience as Eric Porter, Charles Durning, and the role's last London and Broadway occupant, Ned Beatty, Jones is a breed apart. Here are pride and contempt, anxiety and tenderness, robust comedy and roiling anger folded into an overwhelming whole, a onetime fieldhand who has ascended the social scale and then some while remaining impotent against the imminent mortality that lies in wait.

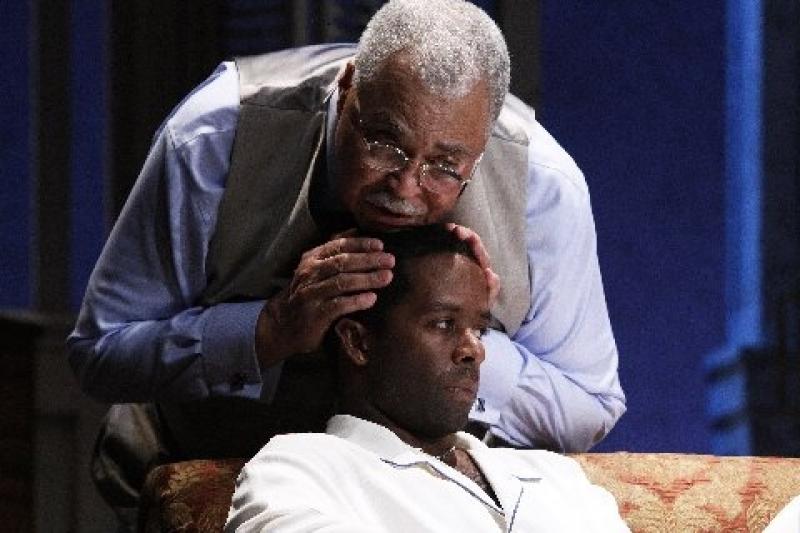

The much-vaunted fact of an all-black cast - or perhaps not: one of the pre-pubescent gaggle of calamitous "no-neck monsters" is very light-skinned - turns out to be of less significance than a renewed awareness of the universality of a playwright who with Cat hit any number of home truths hard. The updating of the action to the 1980s makes one wonder whether the inexplicable "little fever" that felled the former athlete Brick's beloved Skipper might be an early form of AIDS; at the same time, such specifics open on to a view of thwarted communication that may be the only thing, ironically, that binds this family together. Jones at the start is magnificently funny, his face locked into an epic scowl as he attempts to clear an overcrowded room so that Big Daddy and Brick can at last have their talk. (The porous quality of Morgan Large's cage-like set makes plain the lack of privacy that helps drive the plot.) Not long after, though, Jones has passed through scorn and disgust to something infinitely moving, Big Daddy cradling Brick like a father and son fearful of two very different reckonings.

Rashad, a Broadway Tony winner for the same Raisin in the Sun in which Lathan co-starred, got some cool New York notices for Cat, in which case the actress has clearly upped the stakes in the move across the Atlantic. As if to remind us how democratically structured is this play, her Big Mama turns the third act into the awakening of a woman who must confront both the hatred of her husband of 40 years and the extent to which her "precious baby", Brick, has surrendered himself to booze. Dabbing at her eyes, Rashad gives us a mother in near-meltdown, her cheery prattle a heartbeat away from tears.

The British contingent begins with Lester's unusually sinewy, crutch-wielding Brick - flawlessly accented, for those who are wondering - and extends to a pair of remarkably vivid turns from Nina Sosanya and Peter de Jersey as the couple whose ceaseless breeding exists in painful contrast to the barren Maggie. And so Williams's play ends where it began, with Maggie in heat, oblivious (or not) to the chill settling in around her. Her "cat", to be sure, commands attention, but when this Big Daddy lets rip, the entire animal kingdom - not to mention the lucky audience at the Novello - had best watch out.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment