Phaëton, Les Talens Lyriques, Rousset, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

Phaëton, Les Talens Lyriques, Rousset, Barbican Hall

Phaëton, Les Talens Lyriques, Rousset, Barbican Hall

Lully's lyric tragedy about the fall of the Sun's son deliciously animated by supreme stylists

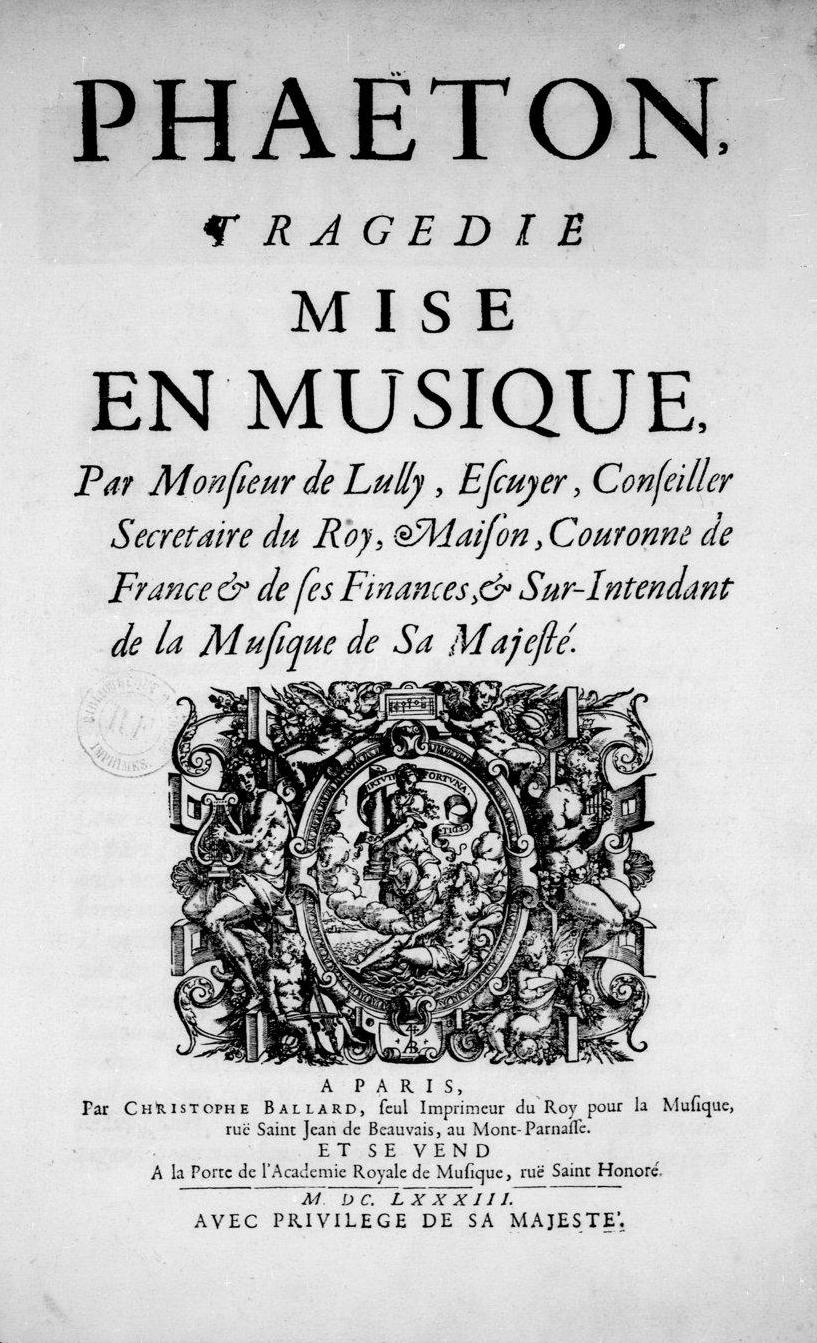

Excess of light and heat sends sun-god Apollo’s son Phaeton tumbling from his father’s chariot. The light was iridescent and the temperature well conditioned as peerless Christophe Rousset led his period-instrument Les Talens Lyriques and a variable group of singers through a concert performance of Lully’s 1684 tragédie-lyrique, a specially pertinent, heliotropic operatic homage to le roi soleil Louis XIV.

Lully was certainly capable of that, as we know from Rousset’s performance and recording of an earlier experiment mixing highly-charged recitative, big choruses and dance, Bellérophon. Phaëton certainly has its moments, though. After a frivolous prologue complete with ubiquitous toadying to the King, strings plunge us into the sudden gravity of Egyptian princess Libye’s plight, with an immediate touch of class in the shape of exquisite soprano Sophie Bevan. All-seeing Proteus’s sombrely coloured prophecy of Phaëton’s fall injects drama into the Act 1 curtain; a dance to conclude Act 2 that could blissfully have gone on for ever makes playful work of the chaconne form with its repeated (in this case chromatic) bass, while the three winds that whisk Phaëton up to see his dad are duly delineated. All is weightless in Act 4's light opening chorus of Apollo’s time-marking courtiers.

Lully was certainly capable of that, as we know from Rousset’s performance and recording of an earlier experiment mixing highly-charged recitative, big choruses and dance, Bellérophon. Phaëton certainly has its moments, though. After a frivolous prologue complete with ubiquitous toadying to the King, strings plunge us into the sudden gravity of Egyptian princess Libye’s plight, with an immediate touch of class in the shape of exquisite soprano Sophie Bevan. All-seeing Proteus’s sombrely coloured prophecy of Phaëton’s fall injects drama into the Act 1 curtain; a dance to conclude Act 2 that could blissfully have gone on for ever makes playful work of the chaconne form with its repeated (in this case chromatic) bass, while the three winds that whisk Phaëton up to see his dad are duly delineated. All is weightless in Act 4's light opening chorus of Apollo’s time-marking courtiers.

Expect the kind of graphics for the arrogant young man’s fatal journey that Saint-Saëns later provided in his brilliant tone poem, though, and you’ll be disappointed. The highlight of the last act is a moving duet for Libye and the man she must forsake to marry Phaëton, his rival Epaphus (a sometimes over-forceful but stentorian Andrew Foster-Williams, good fun in the spat between the two men). We wait for the peripetaia, and it’s over in a flash, as is the opera. Why? Probably because the original stage machine for showing Phaëton’s demise was so spectacular, as Lindsay Kemp told us in his crisp programme note, that Lully didn’t need to do anything with the music.

What keeps us company elsewhere, especially as the silly love-story wrapped around the Phaëton myth takes time to unfold, is the superbly-moulded nature of the French recitative that constantly bursts into heroic (or tragic, or merely dramatic) arioso. Philippe Quinault's libretto keeps a dignified balance between clarity and sententiousness, and Lully, who would declaim the verses to catch the melody in them, knows exactly what to do with it. The finest exponent in terms of both tone colour and text was the regal Ingrid Perruche (pictured above) as Phaëton’s ambitious mother Clymène. Urgency, but not beauty of tone, came from the paint-stripper voice of Isabelle Druet as Phaëton’s not-enough-beloved Théone.

What keeps us company elsewhere, especially as the silly love-story wrapped around the Phaëton myth takes time to unfold, is the superbly-moulded nature of the French recitative that constantly bursts into heroic (or tragic, or merely dramatic) arioso. Philippe Quinault's libretto keeps a dignified balance between clarity and sententiousness, and Lully, who would declaim the verses to catch the melody in them, knows exactly what to do with it. The finest exponent in terms of both tone colour and text was the regal Ingrid Perruche (pictured above) as Phaëton’s ambitious mother Clymène. Urgency, but not beauty of tone, came from the paint-stripper voice of Isabelle Druet as Phaëton’s not-enough-beloved Théone.

Emiliano Gonzalez Toro’s only just steady enough protagonist had the right ring for vaunting ambition, but it was a bad idea to match him with another, paler tenor possessed of a rather peculiar technique, Cyril Auvity, as a less than divine father. Benoît Arnould’s Protée needed the lower bass notes that Matthew Brook possessed in abundance. But the real fluent pleasures came from Rousset’s ensemble, sounding silky-gorgeous in the Barbican Hall – how much better this venue suits a smaller, period ensemble than a big symphony orchestra – with the cellos especially rocking the bass line where necessary, and the supremely cultured Namur Chamber Choir. Rousset could take charge of the telephone directory and we’d probably listen with just as much pleasure. May they come back soon.

Watch Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques in the complete Phaëton at the 2012 Beaune Festival

Read David Nice's blog, I'll Think of Something Later

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment