Ecstasy and Death, English National Ballet, London Coliseum | reviews, news & interviews

Ecstasy and Death, English National Ballet, London Coliseum

Ecstasy and Death, English National Ballet, London Coliseum

A three-course evening out at the ballet with a phenomenal star at its heart

Is it death that makes us go back to the ballet? The one artform where it is so glorified, so exquisitely reimagined as an experience of regret, hope, ecstasy or bleakest resignation that we will go to drink it in again and again, to preview our own? Maybe that’s it. Opera is about living in the threat of death (all those tubercular arias and declarations from the heart of bonfires). Theatre is all about living, imperfectly.

These gloomy, exciting thoughts crowd in for English National Ballet’s brief, stimulating mixed programme entitled Ecstasy and Death at the London Coliseum, in the midst of a week that is sorely testing the ballet pound with fantasies of death. The National Ballet of Canada’s Romeo and Juliet at Sadler’s Wells - pfff. Tonight the Royal Ballet’s magnificently gruesome Mayerling, for those with strong stomachs. But ENB has a three-course banquet for all tastes, a nice body-beautiful starter, a nerd’s-guide-to-classical-ballet finisher - and in between, probably the man of the year, Nicolas Le Riche in Roland Petit’s winey Le Jeune homme et la mort.

Petit was France’s most exciting choreographer for decades, but was too French, too sexy, too philosophique, to become a favoured guest in British companies. One of his last acts before his death two years ago was to permit ENB to acquire his ballet, which is an eyecatching vehicle with only two seats.

He is homme incarnate, tall, intellectual, charismatic, electrically quick and stupendously hot

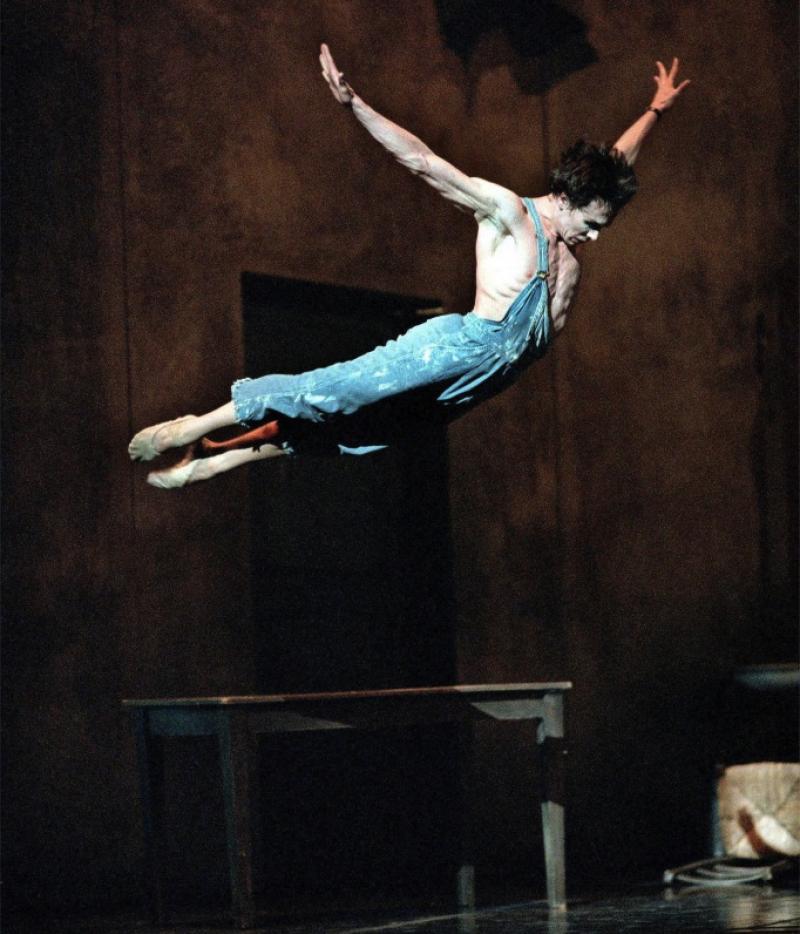

It’s understandable that Tamara Rojo, in launching her ENB directorship, brazenly confessed that she persuaded Paris Opera Ballet’s Le Riche to dance the work with her as a present to herself. It doesn't matter that Paris’s most exciting star for the past 20 years is 41 now - in his one-shouldered denim dungarees he is homme incarnate, tall, intellectual, charismatic, electrically quick and stupendously hot as the eponymous young man lounging about in his garret waiting for someone (probably a girl) to turn up.

He smokes, he checks his watch, he idles about in working time - he is every inch the scrounger on benefits. But this is Forties Paris, so the girl who knocks at the door is not a benefits inspector but Death. She’s a nasty piece of work, as Tamara Rojo dances her, in a deceptively sunny yellow dress, and sinister black gloves. In the Nureyev-Jeanmaire film version Bach's Passacaglia is heard on the organ, with reproachful religious associations - Respighi's soupy orchestration for the live performance drowns the old Catholic guilt in purple musical melodrama.

But it is still bonza theatre. Boy, did Petit know how to grab an audience. The young man veers between electrifying leaps and the freeze of a rabbit in headlights, as Death runs her gloved hands lasciviously over his back. Georges Wakhévitch's grand set unfolds like an explosion at the end, producing the Paris skyline like a rabbit out of a hat. Le Riche takes it all with mesmerising seriousness, even its repetitiousness. He gradually blocks the remorseless femme fatale out of his glazing vision and when he hangs himself it is because some opaque existential loss within him has knocked the support out of his ability to live. Then you collect yourself: come on, it’s French, it’s théâtre, it’s super-mélodrame.

Rojo overplayed the cartoon seductress, I thought; Jeanmaire was smiling, ambivalent, part-mother-part-killer in those early outings, and more lethally ambiguous.

Jiří Kylián’s Petite Mort (pictured above by David Jensen/ENB) makes a complementary hors d’oeuvre to this spicy entrée, but it can’t help being completely eclipsed by the Petit’s sheer ballsiness. "Petite mort" is the picturesque French term for orgasm, and the pictures aim to be sexy - both men and women in rather medical flesh-coloured corsetry, the men swishing fencing épées, the women hugging the black ball dresses they may just have taken off.

Jiří Kylián’s Petite Mort (pictured above by David Jensen/ENB) makes a complementary hors d’oeuvre to this spicy entrée, but it can’t help being completely eclipsed by the Petit’s sheer ballsiness. "Petite mort" is the picturesque French term for orgasm, and the pictures aim to be sexy - both men and women in rather medical flesh-coloured corsetry, the men swishing fencing épées, the women hugging the black ball dresses they may just have taken off.

The impression is rather of a high-class bordello, as two Mozart piano concerto slow movements lay a velvety rug under the male-female couplings. Yet there’s something uncommitted and over-selfconscious about the movement - the pairs seem engaged less in mutual discovery than in an poseurish sort of ballet semaphore, big square-cut arm gestures, knees right-angled and splayed, phrases snatched and jerky. It’s not seductive in phrasing, and the movement abjures intimacy with the music.

The 14 dancers evidently enjoy being bare-skinned and tightless - Ksenia Ovsyanick and Daria Klimentová bringing contrasting dynamics, bold and discreet, respectively - but more conviction would be needed to make this pale stuff less soap and more musk. Though I’m still not sure that would do it.

The finale, Harold Lander’s 65-year-old Etudes (pictured above by David Jensen/ENB), is one of those classroom ballet-cum-display pieces that aim to reassure viewers that the dance company does know its stuff, and ENB has the technique and synchro discipline to pull off the display all right. It is no more than a running commentary on the drill of ballet class which aims to show the gradual maturing into art, but it is 50 minutes long - longer even than The Rite of Spring - and the initial, rather intriguing demonstrations by the girls of the mystery of ballet technique before long cede into third-rate episodes of vaguely “romantic-style” and “classical-style” performance.

At this stage, quite suddenly, the mettle of the dance exercises become arty whimsy, Lander not being Ashton or Balanchine or Petipa. And the music, based by Karl Riisager on Carl Czerny’s piano exercises, ceases to be a quite amusing underpinning for barre practice and becomes a blasted bore, and then blasts on, louder and louder, longer and longer, brassier and brassier.

Erina Takahashi led the troops with her usual feminine delicacy but needs more of the ballerina grand style to lend this the sophisticated wit it begs for, whereas Vadim Muntagirov, boyish and innocent, was a joy of quickness, refinement and airy pizzazz.

Incidentally, the Benois de la Danse, which markets itself as the international ballet Oscars, has nominated Muntagirov, Ksenia Ovsyanick and ENB's house choreographer George Williamson in the male dancer, female dancer and choreographer categories. Other nominees include the Royal Ballet's Edward Watson and choreographer Christopher Wheeldon. Prizes to be announced in the Bolshoi Thatre, Moscow on 21 May.

- English National Ballet performs Ecstasy and Death at the London Coliseum till Sunday

- ENB's website shows related events

Watch ENB's trailer for Le jeune homme et la mort

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Comments

Again a lot of unsold tickets