It's 17 years since Helen Chadwick died without warning of heart failure at the tragically early age of 42 and nine years since the Barbican staged a retrospective of her work. Time, then, for a reappraisal and this small but beautifully presented exhibition at Richard Saltoun’s gallery contains enough gems to remind us of the beauty, wit, intelligence and originality that made the artist and her work so very inspiring.

Showing total disregard for boundaries, she used anything from flowers and rotting vegetable matter to meat, chocolate, fur, wood and bronze, and from photocopies to colour photographs and video in work that spanned the divide between fine art and craft, two and three dimensions and between permanent objects and temporary installations.

Showing total disregard for boundaries, she used anything from flowers and rotting vegetable matter to meat, chocolate, fur, wood and bronze, and from photocopies to colour photographs and video in work that spanned the divide between fine art and craft, two and three dimensions and between permanent objects and temporary installations.

Her example as an artist and teacher helped pave the way for the YBA generation; it's impossible, for instance, to imagine Anya Gallacio’s installations made with flowers or chocolate without the preamble of Chadwick’s Cacao, a fountain of molten chocolate that in the summer of 1994 filled the Serpentine Gallery with its cloying aroma, the daisies on the lawn which she methodically painted black for the occasion and the posies she embedded in nasty chemical products. On show here is Wreath to Pleasure No 2, 1993 a ring of dandelions, encircled in the honey coloured ooze of afro hair gel, photographed and presented in a yellow aluminium frame as emphatically stylish as an Anthony Caro sculpture.

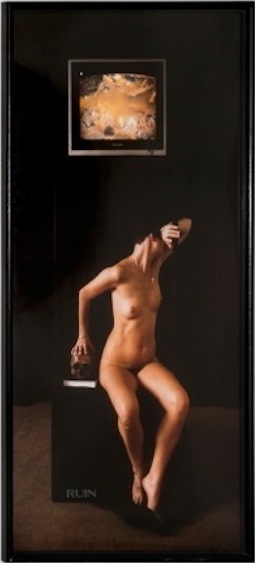

Sam Taylor Wood’s video Still Life, 2001, of a bowl of fruit rotting into fly-blown oblivion would be unthinkable without Chadwick’s Carcass, a tower of rotting vegetable matter installed at the ICA in 1986 while it degenerated into a vat of obscenely bubbling liquid. Here a photograph of the compacted ingredients of the tower is hung beside Ruin (pictured above right), a photographic vanitas in which Chadwick poses naked beneath a video still of the decomposing morass. Her hand rests on a skull, as though she were contemplating not just death but the corruption of youthful flesh into fetid matter. Is it possible that 10 years before her untimely death she had a premonition of her sad fate?

It's hard to imagine Tracey Emin making bronze casts without the example of Chadwick’s bronze cucumbers. Ringed with a neat ruff of fur, the nobbly vegetables remain as provocatively funny as when she made them in 1993. Arranged on a white, kidney-shaped pedestal resembling a cocktail bar, these phallic offerings are like scurrilous nibbles laid out in readiness for a drinks party.

Marc Quinn’s desire to preserve flowers in sub-zero silicone may well be a response to Chadwick’s fascination with flowers and their inevitable decay. Billy Bud, 1994 (pictured above left), is a breathtakingly beautiful photograph of a tiger tulip with stamens replaced by a close-up of male genitals. Framing the male body inside a bloom as though to emphasise its fragility as well as its sexual potency would be a shockingly transgressive idea if it were not realised with such subtle understatement.

But Chadwick was far more than a precursor of flamboyant things to come. During her short career, she not only produced playful, extreme and beautiful works but ceaselessly explored the potential of new media to give expression to her radical ideas. In the photographic series Meat Abstracts, 1989 (pictured right: Meat Abstract no 8), innards such as liver, kidney, tongue, tripe and the yolks of partially formed eggs are arranged on animal skins and folds of silk or velvet – materials normally used to hide, protect and decorate the human form. Instead of focusing on the body’s external surface, the beautiful carapace which has long been a favoured subject in art and which obsesses so many of us, she reveals the hideously vulnerable guts housed within, which we prefer to forget or ignore and which she described as “the hidden profane". She uses them as reminders of our "flesh-hood", the fact that we reside in bodies that are living organisms as well as desirable and desiring objects.

But Chadwick was far more than a precursor of flamboyant things to come. During her short career, she not only produced playful, extreme and beautiful works but ceaselessly explored the potential of new media to give expression to her radical ideas. In the photographic series Meat Abstracts, 1989 (pictured right: Meat Abstract no 8), innards such as liver, kidney, tongue, tripe and the yolks of partially formed eggs are arranged on animal skins and folds of silk or velvet – materials normally used to hide, protect and decorate the human form. Instead of focusing on the body’s external surface, the beautiful carapace which has long been a favoured subject in art and which obsesses so many of us, she reveals the hideously vulnerable guts housed within, which we prefer to forget or ignore and which she described as “the hidden profane". She uses them as reminders of our "flesh-hood", the fact that we reside in bodies that are living organisms as well as desirable and desiring objects.

Beautiful and repellent in equal measure, the images are highly paradoxical. The meat glistens with bodily fluids that suggest freshness and vitality, and among the organs nestle light bulbs symbolising energy and consciousness. Chadwick once told me that her aim was "to reunite mind and body as 'consciousness', which resides in the relationship between energy and matter."

But there is no avoiding the fact that the offal has been ripped from animal carcasses and any semblance of life is false; rather than infusing the lifeless viscera with energy, the heat emanating from the bulbs would speed the process of decay. The images seem to warn that, no matter how much we inform our minds, stimulate our imaginations and beautify our surfaces, the flesh will follow its inevitable journey towards corruption. Ironically, Chadwick sometimes makes the harsh message more palatable by presenting these exquisite photographs in beautiful frames made from leather or bird’s eye maple – as though to suggest that, despite the guts hidden in the belly, it is still worth looking one’s best.

Piss Flowers, 1992 (above and main picture), are among the most celebratory of her sculptures. She and her partner David Notarius urinated in the snow. Her single flow created a deep indent around which he drew a pattern of fluent undulations. When cast in bronze, the forms are inverted so that she produced a single phallic column surrounded by a furl of labial petals made by her partner. Lacquered white to refer back to the conditions of their making, the bronzes resemble rigid bouquets of frozen flowers. Three of them are on show accompanied by a verse written by Chadwick that may not be great poetry, but is a welcome reminder of her mischievous sense of humour. “Locked together you and I/ Bind a hybrid daisy chain/ Organs doubled two a bed and/ By a floral rhyming bed./ Linnaeus what would you say/ How define such wanton play?/ Vaginal towers with male skirt/ Gender bending water sport?”

Piss Flowers, 1992 (above and main picture), are among the most celebratory of her sculptures. She and her partner David Notarius urinated in the snow. Her single flow created a deep indent around which he drew a pattern of fluent undulations. When cast in bronze, the forms are inverted so that she produced a single phallic column surrounded by a furl of labial petals made by her partner. Lacquered white to refer back to the conditions of their making, the bronzes resemble rigid bouquets of frozen flowers. Three of them are on show accompanied by a verse written by Chadwick that may not be great poetry, but is a welcome reminder of her mischievous sense of humour. “Locked together you and I/ Bind a hybrid daisy chain/ Organs doubled two a bed and/ By a floral rhyming bed./ Linnaeus what would you say/ How define such wanton play?/ Vaginal towers with male skirt/ Gender bending water sport?”

Chadwick shone a bright light into the recesses where we keep hidden our deepest fears; and she diffused the terror by looking it in the eye and dusting it with a sprinkling of irreverent wit. Her courage was a challenge and a delight; we must not forget her.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment