Birth of a Collection: The Barber Institute, National Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Birth of a Collection: The Barber Institute, National Gallery

Birth of a Collection: The Barber Institute, National Gallery

A display that celebrates the founding of a forward-thinking arts institute in the heart of the West Midlands

Lady Barber (1869-1933) née Hattie Onions, had her portrait painted in sumptuous style about 30 times, mostly in a sub-Orpen vein, and almost all by the unknown Belgian Nestor Cambier. But that was the very least of her occupations. Her husband, the lawyer Sir Henry Barber (1860-1927), had made a fortune in Birmingham property, and became quite the gentleman.

Their largesse funded what in fact became a prototype for arts centres to come

Hattie was also an accomplished pianist, and the childless Barbers decided that their substantial wealth should fund art and music not only for the University of Birmingham, which would also be accessible to the Midlands public at large. Their largesse funded what in fact became a prototype for arts centres to come in its support for diverse art forms. Even more enlightened, the money was to be used by the university’s experts to support excellence. Lady Barber wanted the eponymous Institute’s collection to aspire to the quality of London’s National Gallery and the Wallace Collection.

To mark the 80th anniversary of the University’s Barber Institute the first dozen paintings that entered the collection are spending the summer at the National Gallery. The gallery first housed this stupendous array of unusual masterpieces while the Barber’s purpose-built home was being built in the 1930s in confident art deco style at the very centre of Birmingham University. The quality of the collection from its outset was due to the Institute’s first director, the redoubtable Sir Thomas Bodkin, who set the standard for the decades to come. Bodkin was a charismatic Irishman who had been head of Dublin’s National Gallery, and he seized the opportunity to make outstanding and imaginative purchases, carrying the university hierarchy and the Barber trustees along with him. Those were the days: the Institute was concerned that they had too much money, and that their resources might even distort the market by raising the asking prices.

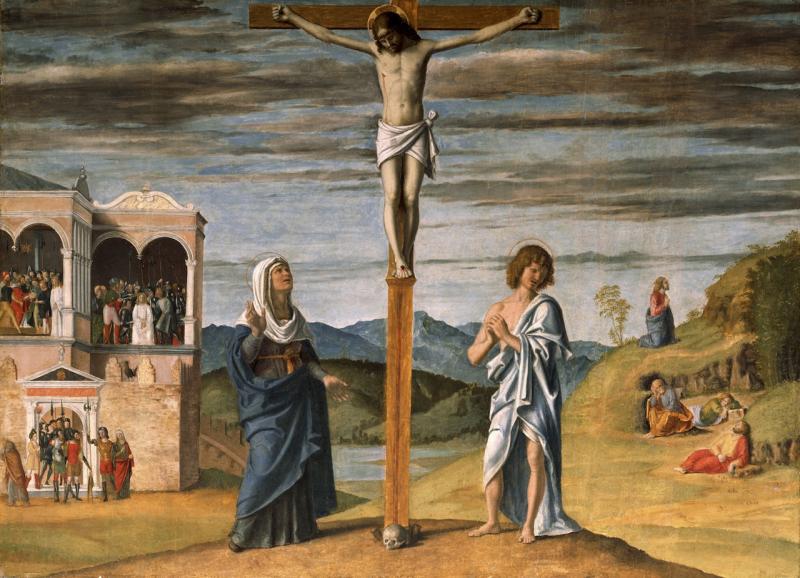

The prices of course seem today totally astonishing, even allowing for 80 years of inflation. The lively informality of Manet’s oil sketch of the French portraitist Carolus-Duran, the teacher of Sargent, cost the Barber £3500 in 1937 from the London art dealers Brown & Phillips, while the evocative Monet The Church of Varengeville cost £1428, from the avant-garde French dealer Durand-Ruel. Ruisdael’s atmospheric Woodland Landscape was £2200, from Tooth, and a Turner masterpiece, The Sun Rising through Vapour for £1350, also from Brown and Phillips. The most expensive painting was the late 15th-century Cima da Conegliano tempera on panel of Christ on the Cross (main picture) from Agnew’s for £8750 in 1938 - the dealer reduced the asking price by £250 - and the next was Frans Hals exceptionally powerful Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull for £6500 (pictured above right).

The prices of course seem today totally astonishing, even allowing for 80 years of inflation. The lively informality of Manet’s oil sketch of the French portraitist Carolus-Duran, the teacher of Sargent, cost the Barber £3500 in 1937 from the London art dealers Brown & Phillips, while the evocative Monet The Church of Varengeville cost £1428, from the avant-garde French dealer Durand-Ruel. Ruisdael’s atmospheric Woodland Landscape was £2200, from Tooth, and a Turner masterpiece, The Sun Rising through Vapour for £1350, also from Brown and Phillips. The most expensive painting was the late 15th-century Cima da Conegliano tempera on panel of Christ on the Cross (main picture) from Agnew’s for £8750 in 1938 - the dealer reduced the asking price by £250 - and the next was Frans Hals exceptionally powerful Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull for £6500 (pictured above right).

All were bought through a network of dealers and auctions, so the show is also a little history of the art market. The language of a deliciously vituperative letter, also on exhibition, denouncing the young Anthony Blunt by William Sabin, the dealer who was selling the Barber the magnificent Poussin mythical scene, Tancred and Emilia (£2000 at the time), is a treat. Although the Poussin has an impeccable provenance, Blunt (referred to not by name but as a certain young man) had doubts as to its authenticity, and only recanted four decades later in that temple of art history, the Burlington magazine. So it was touch and go for a while, and this little glimpse into just one skirmish in the secretive and interconnected world of dealers, auctions, and art historians is both entertaining and instructive.

Bodkin’s refreshing taste was intellectually assured and even advanced for the time. What shines through this mélange of Old Masters and 19th-century paintings is the range of what was available. The Barber started at the top and has remained there, as both a public and a teaching collection, embedded in a university and free to all.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment