There was an unmistakable trend within Modernism to try and record absolutely everything about ordinary life. Think of Joyce and his attempt to set down all of Leopold Bloom’s thoughts, or the cubists and their use of even the tiniest scrap of newsprint in a collage.

The Photographers’ Gallery has had the excellent idea of revisiting Mass Observation, the movement from the Thirties and Forties that wanted to document the mundane to an unprecedented degree. Formed in 1937 at the height of totalitarianism, Mass Observation sounds like it might have been a tool of the police state. Instead it was an entirely benign and curiously English experiment in the social sciences. Participants were encouraged to write down their life stories, but also their daily routines and actions. Diaries and journals were kept. Conversations and passing thoughts were recorded. Everything was photographed. Nothing was too trivial. In fact, the prosaic and the overlooked were the whole point.

It was a deeply democratic impulse to ensure that the stuff of everyday existence should not be entirely forgotten

With no more than two small rooms to chronicle what was a large and varied artistic movement, the gallery has made a decent attempt at providing a flavour of the photographic record, while including a range of supplementary materials. MO, while not a commercial enterprise (or at least, never a particularly profitable one), always aimed to reach a large audience. On display are copies of the books, pamphlets and films the organisation published and disseminated.

Amongst the photographers from the thirties included here, Humphrey Spender produced the work most characteristic of the MO project: crowds and northern street scenes – what it looked like when a factory opened its gates and the workers streamed out.

One of the things that is most intrigu ing about the work on display is how little the politics of the 1930s intruded. It could be the bias of the observers themselves, or the constraints of space in a small exhibition, but from a decade when everything was political, there is hardly anything that suggests the impact that mass ideology had on people’s lives (pictured right: Humphrey Spender, Tom Harrison feigning fear during the Blitz, 1940).

ing about the work on display is how little the politics of the 1930s intruded. It could be the bias of the observers themselves, or the constraints of space in a small exhibition, but from a decade when everything was political, there is hardly anything that suggests the impact that mass ideology had on people’s lives (pictured right: Humphrey Spender, Tom Harrison feigning fear during the Blitz, 1940).

MO recruited volunteers to conduct anthropological research within their own communities or in those they visited across the country. They were encouraged to note down – either openly or clandestinely – overheard remarks or scenes from the street. They looked for the ephemeral and the evanescent: graffiti and the jokes or obscenities chalked on toilet walls. Some of the observers went to surprising lengths to record everything. The exhibition is particularly strong on how and what the observers chose to record. The ornaments on a lodging house mantelpiece would be described and catalogued. A sketch would be made of how they were arranged. When a Bolton housewife got down on her hands and knees to scrub her front step, what movements did she make to complete the washing? What was the radius of the area scoured? An MO report would contain the answers.

It was a deeply democratic impulse to ensure that the stuff of everyday existence and the traces ordinary people leave on the world should not be entirely forgotten. But there were never any final aims for the project, no clear idea of what the mass of data was meant to say. Rather, there was a feeling that it was all, somehow, significant.

So, instead of a sociological study, MO ended up chasing something much more difficult to pin down: the feel and tenor of a place and its people. This produced some striking effects. One observer working in Blackpool on a summer’s evening left a description of the young lovers he saw there. What he wrote might have been a Surrealist experiment in dream writing. It could be the script for a film by Dali and Buñuel:

What actually happens – 11.30 pm, a fine evening on the prom:

The sea is rough, the sand covered

2 men, 2 women. One girl lies on a form, knees pointing up; boy stands gazing down on her.

2 men walk slowly south, larger with left arm round other’s neck.

1 man, 1 woman. Kiss, arm clasped round shoulders, 35 secs.

1 man, 1 woman. He fondles her breasts.

2 men, 2 women. Separate couples kiss standing.

1 man, 1 woman. He gazes into her eyes. Kisses her neck, rubs her nose with his moustache. They peck.

Though it was concerned with Englishness and the doings of the working and middle classes, the project had surprising connections to the cutting edge of art. The Surrealists – then at the apex of their creativity – also thought that meaning was to be found in everyday stuff, that secrets were buried just under the surface of normal existence. They would have been quite at home with MO, whose founders are like a roster of the British arm of the European avant-garde.

Humphrey Jennings was involved in the 1936 Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries; the photographer Michael Wickham was a friend of Braque and Picasso; Julian Trevelyan, as well as being an active Mass Observer, was an artist in his own right. This is Trevelyan bringing the spirit of André Breton to Bolton:

“I cruised round and settled on the outskirts of town near to some cotton mills… At the time I was making collages. I carried a large suitcase full of newspapers, copies of Picture Post, seed catalogues, old bills and other scraps, together with a pair of scissors, a pot of gum, and a bottle of Indian ink. I was applying the collage techniques I had learnt from the Surrealists to the thing seen, and I now tore up pictures of the Coronation crowds to make the cobblestones of Bolton. It was awkward, sometimes in a wind, when my little pieces would fly about, and I was shy of being watched at it; but it was a legitimate way, I think, of inviting the god of Chance to lend a hand in painting my pictures.”

Trevelyan was a prolific artist outside of the MO movement, and the exhibition features a tiny selection of his work. The gallery seems to have acquired loans from the Trevelyan estate rather than from other galleries, so it’s worth checking out what may otherwise not be on public view. One newspaper collage is of the Bolton skyline, with factory chimneys and the gable ends of houses picked out in scraps of newsprint. It looks as if Picasso set out to make a Cubist picture and accidentally came up with a homely Yorkshire scene.

The movement petered out after the 1940s, but there were various reunions and revisitings of the techniques over the years. It was fully revived in the 1980s and, apparently, is still going strong with volunteers keeping diaries, snapping pictures and the rest. The exhibition includes two pictures, taken 50 years apart, of beach scenes (for some reason, MO seems to have been particularly attracted to the slap and tickle of the seaside) that illustrate some of the continuities of English life.

The movement petered out after the 1940s, but there were various reunions and revisitings of the techniques over the years. It was fully revived in the 1980s and, apparently, is still going strong with volunteers keeping diaries, snapping pictures and the rest. The exhibition includes two pictures, taken 50 years apart, of beach scenes (for some reason, MO seems to have been particularly attracted to the slap and tickle of the seaside) that illustrate some of the continuities of English life.

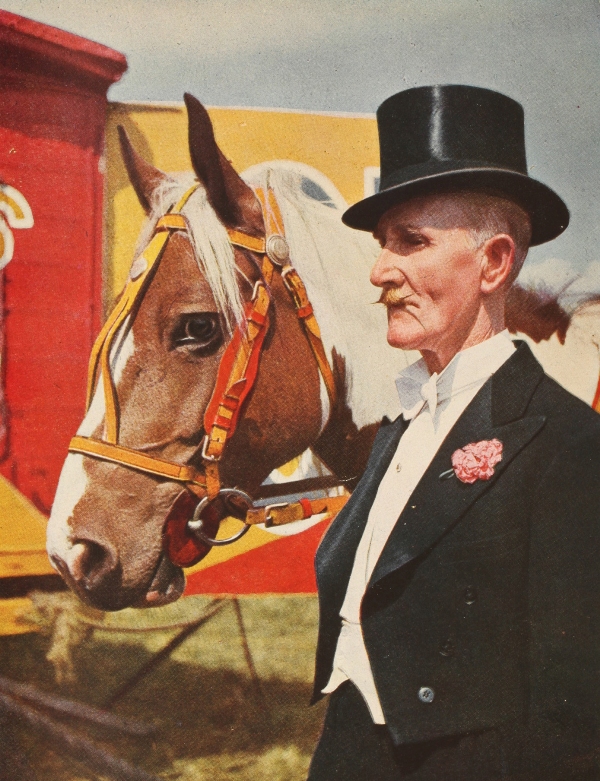

The first, from the Thirties, confirms the stereotype about the English sunbathing fully clothed. The men are in jackets and ties. The women have coats buttoned to the neck. No flesh below the chin is visible. Skip to the Eighties, and the people have learnt to shed a few clothes in the sunshine, but the rhythmic arrangement of bodies and deckchairs and family groups is unchanged (pictured left: John Hinde, from British Circus Life, 1948).

Digital technology means that the dream of recording everything, of capturing it all, is damn close to realisation. So it is unclear what the future of MO might be. A lot of stuff from the current crop of observers as represented in the exhibition seems to be about thoughts and feelings, a record of emotional life; something not even Google Glass is yet able to replicate.

This is a small, ambitious exhibition that has the space to give no more than a brief view of an underexplored subject. The MO archives held at the University of Sussex are, presumably, vast. The Photographers’ Gallery may prove to be early adopters of a particularly rich trove of work. They may be on to something else as well. Filmmaker and MO founder Humphrey Jennings has been a favourite of cineastes for a long time. Recently Danny Boyle resurrected Jennings’s important book Pandaemonium and employed it as the guiding spirit for the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics. Jennings seems increasingly like a giant of the British interwar scene. We need to hear more about him.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment