In September 1899, Claude Monet booked into a room at the Savoy Hotel. From there he had a good view of Waterloo Bridge and the south bank beyond. Setting up his easel on a balcony, he began a series of paintings of the river and the buildings on its banks. So entranced was he by the river that, over the next three years, he came back twice to continue working on a series that would mushroom to over 100 canvases.

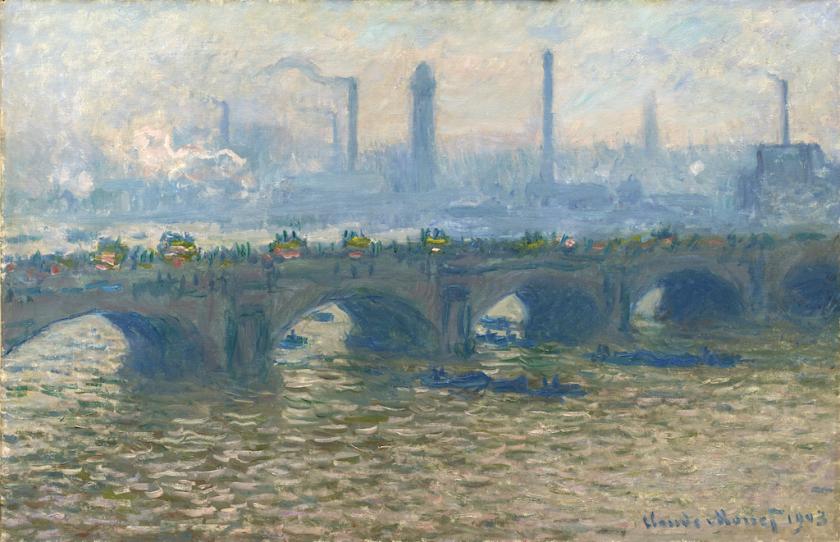

Waterloo Bridge, Overcast 1903 (main picture) shows the bridge packed with pedestrians and horse-drawn, double decker buses picked out in flicks of yellow and red. Making their way through the stone arches are narrow barges heaped with coal, while across the river you can see the south bank bristling with factory chimneys belching smoke. The smoke that filled the air to create extraordinary light effects was what fascinated Monet. “The fog assumes all sorts of colours,” he told a journalist. “There are black, brown, yellow, green, purple fogs and the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs… and the difficulty is to get every change down on canvas.”

The smoke that filled the air to create extraordinary light effects was what fascinated Monet. “The fog assumes all sorts of colours,” he told a journalist. “There are black, brown, yellow, green, purple fogs and the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs… and the difficulty is to get every change down on canvas.”

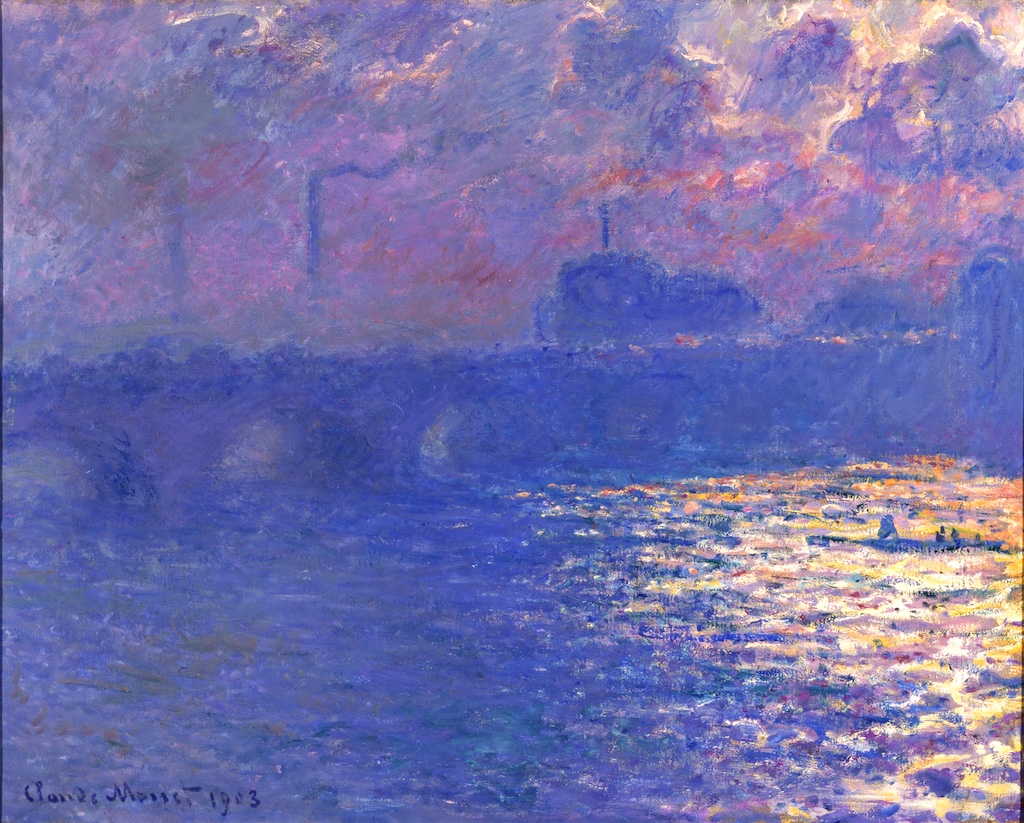

The light changed so fast, in fact, that the only way he could keep pace was to work on dozens of canvases at once, grabbing whichever one most nearly matched the rapidly changing atmospherics. In Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect 1903 (pictured above) the view has shifted a bit to the right where the horizon is dominated by the hulking Waterloo Flour Mill. This time the bridge is little more than a smudgy violet silhouette spanning violet waters tinged bright yellow where sunlight catches the rippling surface. The sky, meanwhile, is filled with billowing clouds of blue and crimson smoke. Never has pollution looked more beautiful and seemed more tangible; the air looks thicker and more substantial than the buildings.

It’s impossible to overstate how radical were these painting. Monet focuses on the intangible – on air, light and weather – and in paintings like Waterloo Bridge, Effect of Sunlight in the Fog 1903, the result is an almost completely abstract rendition of sunlight glinting off water. The Frenchman was obviously influenced by Turner’s sublime evocations of the Thames and James McNeill Whistler’s misty nocturnal views, but never before had anyone focused so determinedly on how light and smog change one’s perceptions and appear to dissolve solid form.

It’s impossible to overstate how radical were these painting. Monet focuses on the intangible – on air, light and weather – and in paintings like Waterloo Bridge, Effect of Sunlight in the Fog 1903, the result is an almost completely abstract rendition of sunlight glinting off water. The Frenchman was obviously influenced by Turner’s sublime evocations of the Thames and James McNeill Whistler’s misty nocturnal views, but never before had anyone focused so determinedly on how light and smog change one’s perceptions and appear to dissolve solid form.

Monet returned to London in February 1900, having got permission to paint the Houses of Parliament from a terrace of St. Thomas’s Hospital on the south bank. In this series the familiar silhouette of Charles Barry’s gothic pile is transformed into a mysterious set of pinnacles shrouded in a blanket of smog that turns it into a ghostly apparition. In Houses of Parliament, Sunset, 1900-1903 (pictured above), for example, the orange ball of the sun seems more substantial than the building, which is shrouded in a dark pall of lavender and crimson mist.

In London, Parliament. Sunlight in the fog, 1904 (pictured below) the building appears like a mirage hovering above and dissolving into the river. Sweeping across the canvas, a swirl of brush marks cradles the lavender spires in a nest of light coloured pink, orange, lilac and yellow, while the sun transforms the water into in a blaze of fiery orange.

On his return to France, Monet set about transforming his rapid impressions into finished pictures and, in 1904, he exhibited 37 of them at his gallery in Paris. The show met with enormous success. The pictures flew off the walls, but this made it impossible to stage a London show the following year, since buyers couldn’t be persuaded to part with their new treasures.

On his return to France, Monet set about transforming his rapid impressions into finished pictures and, in 1904, he exhibited 37 of them at his gallery in Paris. The show met with enormous success. The pictures flew off the walls, but this made it impossible to stage a London show the following year, since buyers couldn’t be persuaded to part with their new treasures.

120 years later, the Courtauld has gathered together 18 paintings from the Paris show and augmented them with three others to create a vivid sense of that first exhibition and of London choking in the pollution that Monet revelled in and Sadiq Kahn has done so much to eradicate.

- Monet and London: Views of the Thames is at the Courtauld Gallery until 19 January

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment