Much Ado About Nothing, Old Vic | reviews, news & interviews

Much Ado About Nothing, Old Vic

Much Ado About Nothing, Old Vic

A transatlantic reworking of Shakespeare's wordy comedy gets lost in translation

“What, my dear Lady Disdain! Are you yet living?” Surely never before has Benedick’s opening quip cut so close to the literal, nor drawn such a laugh from its audience. With a combined age of 158, the romantic leads in Mark Rylance’s Much Ado About Nothing take the current trend for an older pair of lovers to the extreme.

In an effort to showcase his stars at their most natural, Rylance relocates the action to 1940s England. Don Pedro’s troops become a khaki-clad bunch of American GIs and Leonato’s household the motley retainers of a country house, lacking only the Labradors to complete the tale of their cable-knit pullovers, corduroy and wellies.

James Earl Jones is still not master of his lines, sending verbal shot after shot into the net

Redgrave’s Beatrice enters with a brace of dead rabbits, tossing them casually over the back of a chair like a handbag. Later she comes to summon Benedick to dinner brandishing a bloody carving knife, smearing the gore across her white apron. Sadly these are the only hints of the violence that lies so near to the sunny surface of a comedy in which virgins become whores and weddings funerals in an instant. Beatrice’s touchstone of a line – “Kill Claudio” – was met with an uncomplicated laugh, something that could never happen if the text were given its full emotional range. As it is, Danny Lee Wynter’s Don John (despite his pronounced disfigurement) hasn’t a hope of real menace, coming straight as he does from panto playbook or perhaps Carry On Sneering.

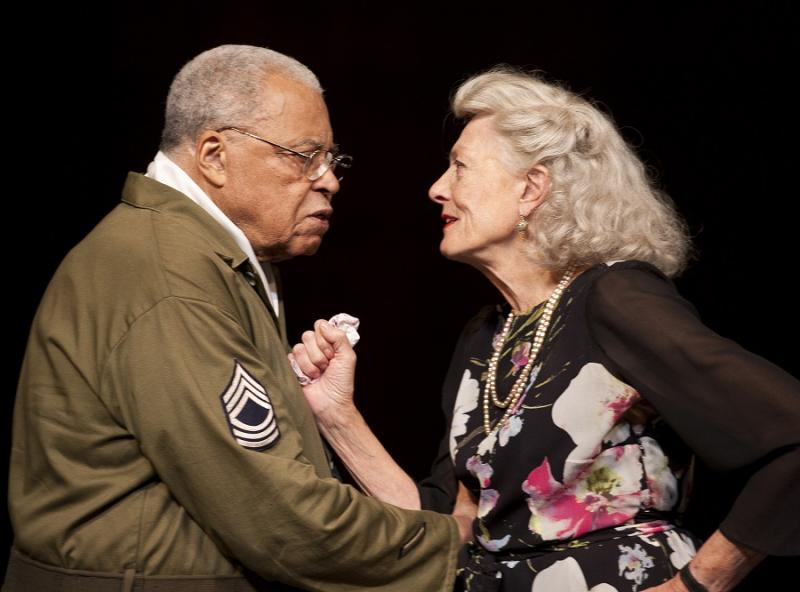

Diction in Ultz’s stylised wooden interior (at baffling odds to the rest of the production) is a serious issue. American accents thicken an already booming acoustic and it’s a struggle to catch the details of this nimblest of verbal displays. Although greatly improved by all accounts from the previews, James Earl Jones is still not master of his lines, sending verbal shot after shot into the net, unbalancing the elegant symmetry of Benedick’s constructions and leaving us tense until his safe arrival at each final full-stop. Even Redgrave worries (pictured above right with Beth Cooke as Hero), punctuating her dialogue so oddly as to lose the sense at times, and is only carried through a gently unfocused performance by her still-potent charisma.

Diction in Ultz’s stylised wooden interior (at baffling odds to the rest of the production) is a serious issue. American accents thicken an already booming acoustic and it’s a struggle to catch the details of this nimblest of verbal displays. Although greatly improved by all accounts from the previews, James Earl Jones is still not master of his lines, sending verbal shot after shot into the net, unbalancing the elegant symmetry of Benedick’s constructions and leaving us tense until his safe arrival at each final full-stop. Even Redgrave worries (pictured above right with Beth Cooke as Hero), punctuating her dialogue so oddly as to lose the sense at times, and is only carried through a gently unfocused performance by her still-potent charisma.

The real joy is in the supporting roles. Although wayward in shaping the play’s larger arcs, Rylance’s direction finds unexpected tenderness in moments – Alan David’s Antonio, shuffling gamely forward to defend his niece’s honour, creates an intensity and stillness missing elsewhere, a glorious jazz-spiritual of a “Sigh No More, Ladies” – while the substitution of a troupe of Scouts for the watchmen turns a laboured episode into an unexpected joy. James Garnon is reliably strong as Don Pedro, creating something human of this stuffed-shirt of a prince, and veterans Peter Wight (Dogberry/Friar Francis) and Michael Elwyn (Leonato) anchor proceedings in the familiar.

Perhaps it’s in the crooning depths of Jones’s voice, perhaps in the arthritic swagger of Redgrave’s stride, but there is something here of love and affection that isn’t accounted for by the nuts and bolts of production and performance. Much Ado is a comedy of words – dialogue is not only exposition but also theme and argument too. Words create reality, create love where none was, turn an innocent into a whore. Take these away and you are left with something fragile and neutered. Energy sways where words fail here, and in the midst of a chaotic production something contradictory is salvaged. It’s testimony to Shakespeare rather than Rylance though – even without the words, he still manages to find something to say.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Add comment