Uchida, London Symphony Orchestra, Ticciati, Barbican | reviews, news & interviews

Uchida, London Symphony Orchestra, Ticciati, Barbican

Uchida, London Symphony Orchestra, Ticciati, Barbican

The great pianist ineffably projects Mozart's joy and sorrow, while the conductor lilts in Dvořák

Rumour machines have been thrumming to the tune of “Rattle as next LSO Principal Conductor”. Sir Simon would, it’s true, be as good for generating publicity as the current incumbent, the ever more alarming Valery Gergiev.

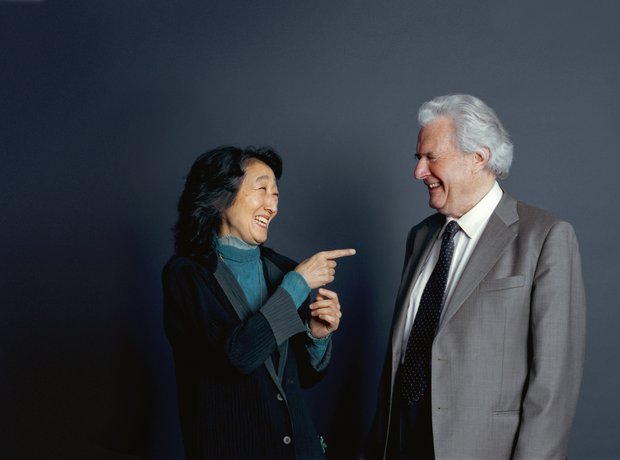

If that more interesting appointment were to be made, we can be sure that the LSO’s beloved Sir Colin Davis, with his unstinting championship for youth, would be looking down approvingly from Up There. This concert was long ago scheduled to be his, and it’s not the first where Ticciati has stepped confidently into the breach. Mitsuko Uchida was there to wave her magic wand right at the start, dedicating Mozart’s Rondo in A minor to Sir Colin (pictured with Uchida below by Gautier Deblonde), who adored it, and hoping as she wrote in the programme to make amends for what had been a bad performance in his studio by playing it “one more time, somewhat better prepared!”

That’s an understatement of the miracle that happened. A single audience-stilling note of E led us tenderly into a clear-sighted but unpredictable journey of gentle melancholy, consolation and even anger: here was the complex humanity of later Mozart in the hands of one who instantly understands the essence. Uchida’s turns and sideslips were perfect, her projection into the large hall as fine as if she were playing for each one of us.

That’s an understatement of the miracle that happened. A single audience-stilling note of E led us tenderly into a clear-sighted but unpredictable journey of gentle melancholy, consolation and even anger: here was the complex humanity of later Mozart in the hands of one who instantly understands the essence. Uchida’s turns and sideslips were perfect, her projection into the large hall as fine as if she were playing for each one of us.

That understanding of human nature, joy and sorrow seamlessly interwoven, continued with the wonderful partnership of Ticciati and the LSO in the G major Piano Concerto K453. It’s always apparent that the galanterie with which Mozart as often begins soon turns inward, but Ticciati had an extra shock in store first by turning it fiercely outward: not for him, or Uchida, the weak image of Mozart as sweet rococo child. The bittersweet second theme, with its keenings making a happy outcome uncertain, was ineffable from both orchestra and then soloist, strings shading their support chords with just as much care as they had the theme itself.

If anything, the slow movement trumped that. Ticciati has always dared to extend silences in music – his Glyndebourne Jenůfa was a searing first lesson in how effective that can be – and they were instrumental in creating suspense as to what the answers to the Andante’s many questions might be. What modulations, what surprises. And then we were encouraged to laugh out loud at the robust wit of the finale’s variations, from the piano’s first delighted entry to the horn charge of the coda, though again there were shadows in the nearly-naked minor variation.

Ticciati delighted in the fire and the wood magic of twilight-zone string rustlingsNaughtily, the LSO hadn’t really advertised an interloper, the world premiere of The Calligrapher’s Manuscript by Matthew Kaner, a participant in the Helen Hamlyn-supported LSO Panufnik Young Composers Scheme. Kaner knows how to put across high and low sonorities, and his woodwind curlicues did convey something of his subject's florid lettering. But the twittering of his first half and the doodles of the second still failed to step up to the mark as foreground interest; as with so many new pieces, it’s the process rather than any strong hooks for the audience which seems to interest the composer. Still, he likes the idea of melody, so let's see what happens next.

There are no problems with thematic hooks in Dvořák’s all too rarely performed Fifth Symphony: they flow in bucolic abundance from the first delighted, gurgling clarinet melody, even if the composer doesn’t always know what to do with them, symphonically speaking. Ticciati delighted in the fire, the free sweep of the first movement’s lyrical respite and the flow of the cellos’ bittersweet Dumka melody in the Andante con moto, the wood magic of twilight-zone string rustlings. And the buoyant Slavonic Dance of the scherzo suggested that this team might tackle the complete sets. It always comes as a bit of a disappointment to me that Dvořák has to lay on an unwarranted sense of struggle in the finale, energetic though it was here, and that he has to end in loud triumph. You just wish he could have laid it all to rest with more forest murmurs, and never more so given the poetry of this very Bohemian performance.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

First Person: Manchester Camerata's Head of Artistic Planning Clara Marshall Cawley on questioning the status quo

Five days of free events with all sorts of audiences around Manchester starts tomorrow

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Comments

Yes, indeed! David, sincere

Sincere thanks, too, for your

Sincere thanks, too, for your eloquent reasoning, Hedgehog - not just because it's flattering and of course I agree with every point. I'm only sorry you're stuck with the annoying public comment facility whuch doesn't cater for paragraph breaks. I urge readers not to be put off by that and to pay it careful attention.

I didn't know that patronizing remark from Rattle and I, too, would hold up Jurowski as a shining beacon of how to animate an orchestra and bring fresh audience blood into the bargain. Musical times have never been more exciting in London, though the LSO with Gergiev - despite some interesting rep choices - is not often part of that.