Renaissance Impressions, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Renaissance Impressions, Royal Academy

Renaissance Impressions, Royal Academy

Georg Baselitz’s extraordinary collection of 16th-century woodcut prints

Georg Baselitz might seem an unlikely connoisseur of 16th-century prints, but since the Sixties the controversial German artist has amassed a collection of chiaroscuro woodcuts to rival that of any museum.

Supplemented by loans from the Albertina, Vienna, Baselitz’s extraordinary collection follows the progress of the chiaroscuro woodcut from its invention in Germany through its rapid development across Italy and the Netherlands. Both Lucas Cranach and Hans Burgkmair the Elder claimed credit for the invention and Burgkmair’s portrait of Hans Paumgartner, 1512, demonstrates the capacity of the medium to render texture and volume, the luxuriant, hazy softness of Paumgartner’s fur collar captured entirely with line and tone.

Cranach and Burgkmair each produced chiaroscuro woodcuts dated 1508, Burgkmair’s St George and the Dragon, c.1508-10 (pictured left), using a key block with which the black lines were printed, and a single tone block coloured with a light brown ink. Far from simply adding colour to a monochrome image, the tone block creates highlights and mid tones which add depth and form to the modelling. Significant areas of the paper are left white, and it is this use of highlights that really defines the chiaroscuro – light and shade – woodcut technique.

Cranach and Burgkmair each produced chiaroscuro woodcuts dated 1508, Burgkmair’s St George and the Dragon, c.1508-10 (pictured left), using a key block with which the black lines were printed, and a single tone block coloured with a light brown ink. Far from simply adding colour to a monochrome image, the tone block creates highlights and mid tones which add depth and form to the modelling. Significant areas of the paper are left white, and it is this use of highlights that really defines the chiaroscuro – light and shade – woodcut technique.

It is perhaps not surprising that Dürer, the great printmaker of the time, remained unmoved by this innovation, concluding, rightly enough, that he had no need of colour when he could perfectly well express all that he wanted with black lines alone. Indeed, after Dürer’s death in 1528, Erasmus eulogised: "Dürer, though admirable also in other respects, what does he not express in monochromes, that is, in black lines. Light, shade, splendour, eminences, depressions". Dürer knew how to make minute tonal gradations within a single block, and in many ways, his fellow printmakers were using the chiaroscuro technique simply to emulate Dürer’s finesse, using the tone block to enhance an essentially linear design.

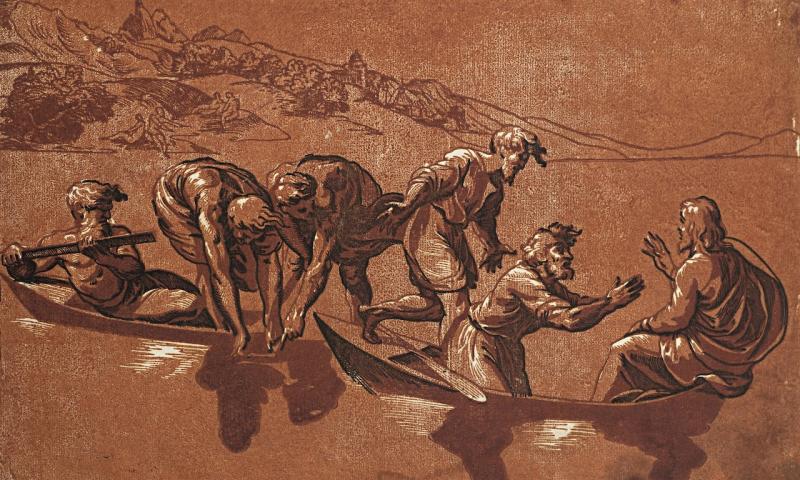

The painter and woodcutter Ugo da Carpi introduced chiaroscuro woodcut to Italy, and it was he who unlocked the painterly qualities of the form, recognising that the tone block could have a purpose beyond complementing the lines of the key block. Ugo’s print after a drawing by Raphael, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, 1523-27 (main picture), uses three blocks; the two tone blocks use gradations of red, one of which is boldly printed across the entire sheet, while the black is kept to a minimum, providing accents and occasional areas of deep shadow. Bright white highlights add to the sense of movement and vigour, and the print has all the immediacy and panache of a sketch.

Some of Ugo’s prints are here in different states, and it is fascinating to see how he and his pupils would reprint an image, using different tones to explore the effects of light and shade. Like Ugo, two of his pupils, Antonio da Trento and Niccolò Vicentino, translated drawings by Parmigianino into print form. The way that these two worked, often producing prints of the same drawing, not only reveals something of the workings of Parmigianino’s workshop, but shows how differently the same drawing could be interpreted by individual woodcutters. Antonio da Trento’s chiaroscuro woodcut of Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyll, c.1529-30, is shown next to Vicentino’s treatment of the same drawing, but where da Trento’s print is graphic and linear, Vicentino’s print is fluid and painterly, and it is interesting to imagine how Parmigianino may have enjoyed the variety of interpretations given to his drawings. (Pictured right: Hendrick Goltzius, Bacchus, c.1589-90.)

Some of Ugo’s prints are here in different states, and it is fascinating to see how he and his pupils would reprint an image, using different tones to explore the effects of light and shade. Like Ugo, two of his pupils, Antonio da Trento and Niccolò Vicentino, translated drawings by Parmigianino into print form. The way that these two worked, often producing prints of the same drawing, not only reveals something of the workings of Parmigianino’s workshop, but shows how differently the same drawing could be interpreted by individual woodcutters. Antonio da Trento’s chiaroscuro woodcut of Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyll, c.1529-30, is shown next to Vicentino’s treatment of the same drawing, but where da Trento’s print is graphic and linear, Vicentino’s print is fluid and painterly, and it is interesting to imagine how Parmigianino may have enjoyed the variety of interpretations given to his drawings. (Pictured right: Hendrick Goltzius, Bacchus, c.1589-90.)

Back in Germany, Erasmus Loy was developing the chiaroscuro woodcut in quite a different direction, using the tone blocks to dramatic effect in graphic architectural views, like Courtyard with Renaissance Architecture, c. 1550. These prints were sold as wallpaper that could be pasted onto walls and furniture as a cheap alternative to marquetry, the bold arrangements of black, brown and highlights mimicking the effects of inlaid wood.

That focusing on such a specific area of printmaking can produce a wide-reaching and varied exhibition only emphasises the scale and quality of artistic activity in Renaissance Europe. Works by Domenico Beccafumi and Andrea Andreani give some insight into the ambitions of Italian printmaking of the 16th century, while chiaroscuro woodcuts by Hendrick Goltzius show the technique used to create atmospheric landscapes that explore the effects of light in conditions ranging from bright sunshine to a brewing storm. The exhibition’s narrow focus risks seeming arcane, but actually serves to elucidate just some of the preoccupations and practices of artists in this golden age of printmaking.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment