Classical CDs Weekly: Prokofiev, Schubert, Zemlinsky | reviews, news & interviews

Classical CDs Weekly: Prokofiev, Schubert, Zemlinsky

Classical CDs Weekly: Prokofiev, Schubert, Zemlinsky

Blistering piano concertos, emotionally draining chamber music and a pair of late-romantic symphonies

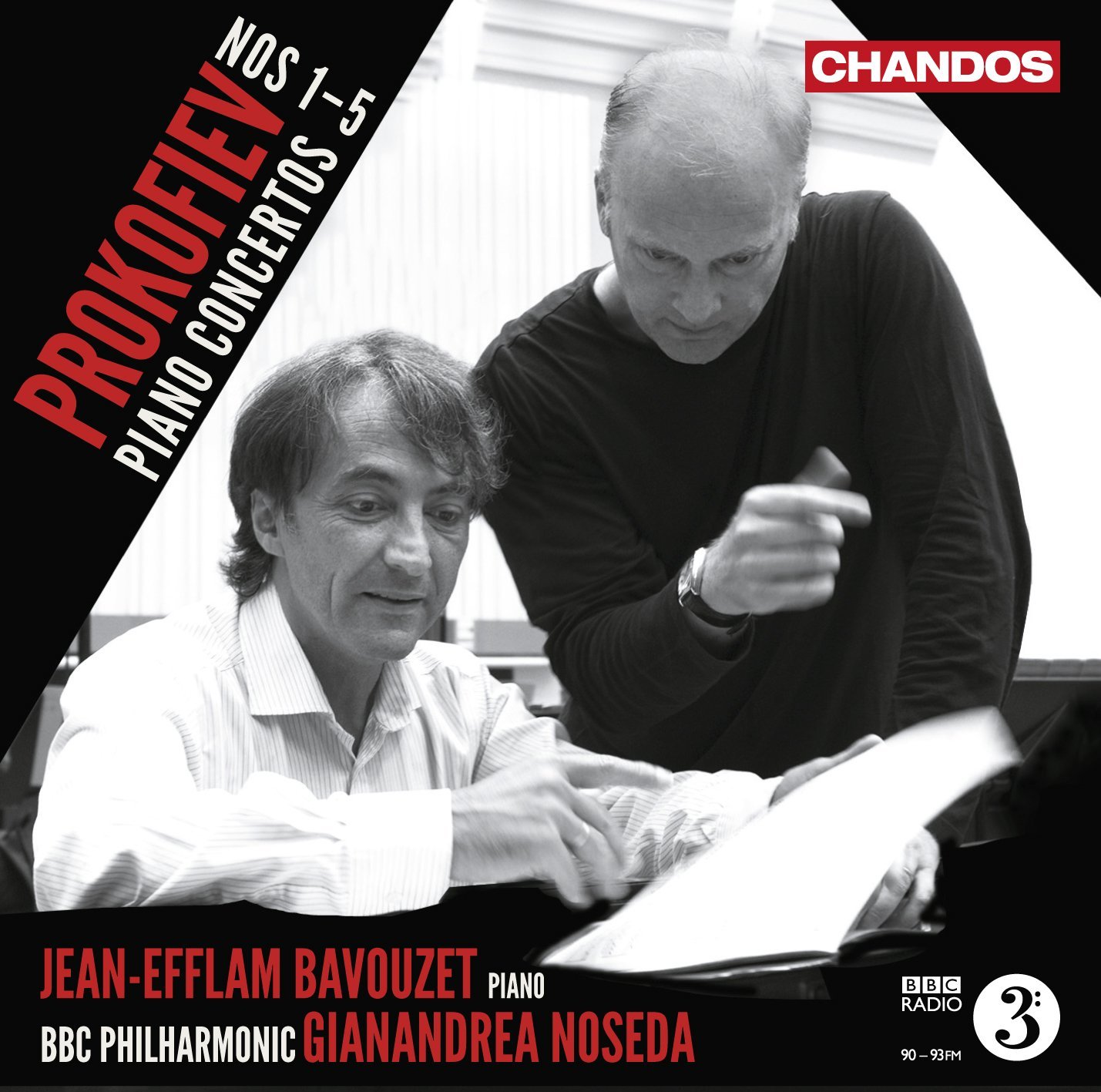

Two of Prokofiev's five piano concertos are so well-embedded in the repertoire that they tend to dwarf the other three. So it's great to have the whole lot squeezed comfortably onto a pair of discs. I've long enjoyed Ashkenazy's 1970s accounts, accompanied by a beefy LSO under André Previn. Jean-Efflam Bavouzet's playing is rather different; he realises that there's more to Prokofiev than pure brawn. Not that these performances are lightweight in any sense – the remorseless cadenza in the first movement of No. 2 is rightly gruelling here. Such a wonderful, theatrical moment, the orchestra's muscular lower brass almost drowning out the soloist. But we'll get back to 2 and 3 later. Turn to the second disc, and dive into the seldom-heard 4th concerto for left-hand only. This was commissioned by an ungrateful Paul Wittgenstein. He never actually performed it, telling a disappointed Prokofiev that he didn't understand the music; Prokofiev's plans to rework it for both hands were never realised. Bavouzet's reading is the best I've heard – sparky in the brittle moments, finding unexpected depths in the second movement's Andante. The finale hangs together well, and that tiny coda, abruptly condensing the first movement's material into 90 seconds, is brilliantly realised. Bavouzet is just as persuasive in No 5. This is an occasionally baffling work, but his reading will make you smile.

Gianandrea Noseda's nimble BBC Philharmonic are well-matched partners – not as sumptuous as some rivals, but rhythmically alert. Muted strings catch to perfection the noirish swoon of No. 1's slow movement, and the brassy big tune is all the more potent for never lingering. No. 2's Scherzo and Finale are breathtaking. No. 3 is light-footed, witty and propulsive. All concerned sound as if they're enjoying themselves. Comprehensive notes from Prokofiev expert David Nice too, and good Chandos sonics.

Franz Schubert was familiar with the work of 18th century poet and composer Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart's 1806 Reflections on an Aesthetics of Music, which includes an entertaining rundown of the characteristics of different musical keys. Schubert's Death and the Maiden quartet is in D minor – then an unusual choice for a chamber piece. Schubart associated it with “melancholy womanliness”, one in which “the spleen and humours brood”. Not very promising, though at least Schubert didn't opt for F Minor, a tonality redolent of “deep depression, funereal lament, groans of misery and longing for the grave”. This quartet is a big-boned, uncompromising work, containing many moments when the music almost buckles under its own expressive weight. You really feel the pain in this bold performance, the impact heightened by a close recorded balance. The Pavel Haas Quartet's cellist Peter Jarůšek's is one of this group's greatest assets, anchoring every grinding chord with dark weight and closing Schubert's first movement with a weary shrug. Equally good is the Presto's shadowy opening, and the quartet's final chords sound like a heavy door slamming shut.

And we've a generous coupling; an emotionally generous reading of Schubert's vast C major Quintet. Adding a second cello makes the sonorities richer still, and the Haas Quartet tread with some skill a fine line between intimacy and extravagance. This is a brilliantly assertive, large-scale reading. But these players always know when to step back; the Adagio's more ethereal strains are painted with heartbreaking poignancy. The Allegretto's final bars are overwhelming, outright triumph undermined by that snarling semitone. Glorious, thought-provoking music. I can't think of many more productive ways of spending 54 minutes.

As a young composer, Alexander Zemlinsky was supported by the ageing Brahms. He became a friend of Schoenberg and was, for a time, the composition teacher and unlikely lover of the young Alma Schindler, who then went on to marry Mahler. He's a fascinating transitional figure. Several of his works have a toehold in the repertoire, notably the gorgeous Lyric Symphony which owes a huge debt to Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde. Zemlinsky's two orchestral symphonies are from his student days, but they're hugely assured, enjoyable pieces, filling in the gaps between Brahms, Strauss and Mahler. Brahms was in the audience for the premiere of the 1892 Symphony in D minor. You feel that he would have been impressed; Zemlinsky's dark orchestral colours suggest the older composer without ever sounding like too obvious a tribute, and the first movement has a confident sense of purpose and plenty of forward motion. The slow movement recalls both Dvořák and Bruckner, and if the finale's blazing D major conclusion doesn't quite feel hard-earned, it's brilliantly scored.

More impressive is the 1897 Symphony in Bb. The descending horn call at the start is such a simple yet memorable idea – nostalgic, bucolic, bidding farewell to a musical culture and tradition already on the wane. The ensuing Allegro has infectious swagger, the Scherzando has Mahlerian bounce and the Adagio is marvellous. Zemlinsky alludes to the passacaglia of Brahms 4 in his finale. As with the earlier work, the dramatic major key coda sounds as if it's been clumsily bolted on as an afterthought, but it provides plenty of uplift. Hyperion's sound is glowing – one of the richest recordings they've issued. Martyn Brabbins's BBC Welsh players raise the roof in the noisier climaxes, and the notes are excellent. Lovely sleeve art too.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Add comment