10 Questions for Drummer Billy Cobham | reviews, news & interviews

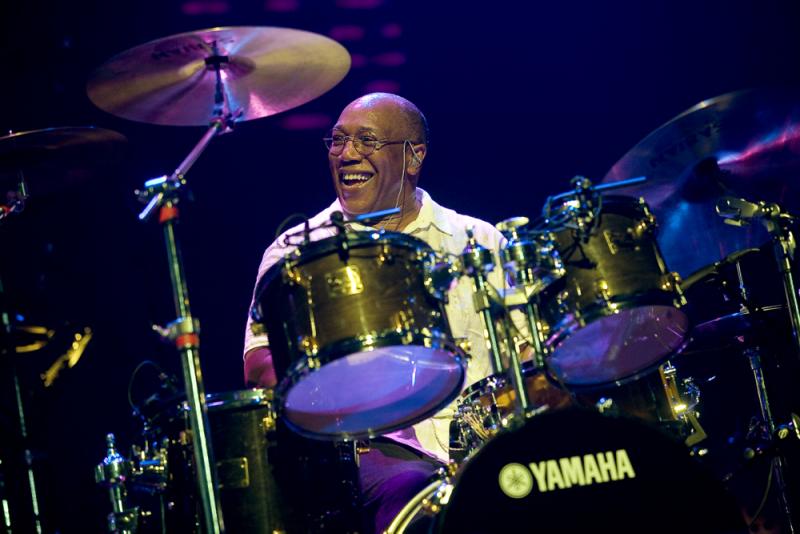

10 Questions for Drummer Billy Cobham

10 Questions for Drummer Billy Cobham

Fusion pioneer on creativity, drummer-bandleaders and the triple effect of a hotter climate

Drummer Billy Cobham has been an innovative and influential figure since the 1960s across jazz, Latin, funk and the areas of fusion between. He has played with Horace Silver, Miles Davis, Randy and Michael Brecker, and in 1971 was a founder-member of John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, widely considered to have been the greatest jazz-rock fusion group of all.

When the Mahavishnu Orchestra disbanded in 1973, Cobham began leading his own groups, and releasing albums in his own name. The first of these, Spectrum (1973), is generally regarded as one of the defining statements of the jazz-rock genre, and Cobham’s significance in creating and defining the genre stands alongside the contributions of Davis, Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Wayne Shorter. Cobham has continued to perform, record and teach, and his influence on the development of drumming and its role in all jazz-related genres remains huge.

He spoke to theartsdesk about fusion, creativity, turning 70, and the curious tripling effect of a hot climate.

MATTHEW WRIGHT: When Spectrum was released in 1973, did you think you were doing something ground-breaking? How do you look back on that moment now?

BILLY COBHAM: It was a mistake. I didn’t know I was doing anything. I was making a record based on my experiences, based on who I’d worked with: I wasn’t going out of my way to break new ground, it was just who I was, that’s all the reputation means. You have to keep in mind that the people talking about it now didn’t exist back then.

The silent word we’re not using is competition: music is not sport, it’s not the Olympics

How did that sound come about? What were you trying to create? Was it experiment, or a sudden brainwave, that brought all of those elements together?

I’ve played and recorded with funk bands, Latin bands, and jazz bands. I took a piece from each genre and applied it to what I knew. My recordings have a lot to do with my history as an artist, as a musician. Every sonic element in the music reflects who Billy Cobham was and is.

You’ve said that you find it difficult to concentrate on one musical style: is this where fusion comes in?

I’m not consciously doing that. I take whatever is given to me, musically, if I feel I can be effective, contributing to the musical poker table.

You’ve been heavily involved in Cuban music and WOMAD, as well, of course, as the Mahavishnu Orchestra: what is it that draws you to the music of other cultures?

The foundation and trigger for me is the same trigger in music all the way around the world: whatever is coming through, if I hear something I can relate to, I try to work with it. I’m always changing conceptually, always listening, not closed. As long as something comes to me I can relate to, then I'm fine, and I try to use it in my own conception, to stimulate the cross-pollination of ideas. No musician in the world creates anything entirely by themselves.

There are, obviously, a number of distinguished drummers leading bands, though some critics say they can become too interested in pyrotechnics and not enough in getting the other members to play together. What’s your experience of the challenges of leading a band as a drummer?

Nine tenths of it is sitting behind everybody pushing, whereas a sax player is pulling. I only take over if it’s musically effective to do so. The silent word we’re not using is competition: music is not sport, it’s not the Olympics. We’re creating a sonic image of players on the bandstand, we all contribute to that image, and if everybody works together you have a band projecting personality. It’s all about teamwork, not anybody doing better than anyone else. When people get the idea, the band does well. That’s what I want them to walk away with.

Where do you think the next new frontier in jazz is? Is it all electronic? Are there new kinds of fusion to try?

I don’t know. I only only think about getting to the next level. I have trouble getting to where I am, playing as well as I am right now. You have to know all about how you use this skill to access the instruments that make things sound different, as well as the imagination and brainpower. All these things are manufactured, they won’t play themselves.

You’ve played with Horace Silver, Miles, John McLaughlin’s Mahavishnu Orchestra, so many exciting bands: what do you think are the highlights, looking back on your career?

I don’t see particular moments as highlights. It’s been a wonderful life, because it needs to be that way. Generally the one most important image in my mind is that I've had a consistent way of working from day to day, doing what I love most. I’ve been associated with some great great people, people who are very interesting personalities, whether negative or positive. There’s some positive from everyone. I just play - most of the stuff written about me may or may not be true...

Most people in tropical regions tend to function in rhythmic patterns of triplets

You’ve made some bold statements about the importance of music as a means of bringing people together, having been involved with UNICEF for some years: what’s your experience been of how it works? What would you like to see done next?

Just be yourself! The fundamental thing in music is us and we are music. Every work that comes out of your mouth is music, it’s all part of your assigned image, if what you say is true.

What does that mean in practice?

Take note of the Tropic of Cancer and Capricorn, then go to a place like Brazil. Most people inside those regions tend to function in rhythmic patterns of triplets. They appear to walk slower, but they broaden their gait one third more than those who live above or below, where it’s much colder. Go to Guatemala, they walk in triplets; all the way round Africa, too. That’s the way life is, everything is sonically represented through those images. Mexico was supported and influenced by the West after the French invasion (1861-7). The French came with their troops and military bands, and the Mexicans retained that afterwards. Flamenco is also very duple-oriented, but as soon as you take that Spanish concept south to Panama, the rhythms work in triple, and further south, everything does.

At 70, do you look forward or look back? What are your musical plans now?

I’m looking forward to making it to 70, sure. Getting there is fine. Now I’m thinking what do I have to offer? What can I share with my public, in Cheltenham, to make it a special situation? I’m thinking about how I have to internalise my art form to make a great concert. My latest project, Tales from the Skeleton Coast, about my musician parents, will be available in Cheltenham.

- Billy Cobham plays a special 70th birthday celebration concert at the Cheltenham Jazz Festival on 4 May

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

Comments

Bill Cobham and Alphonse