theartsdesk Q&A: Singer Sonja Kristina | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Singer Sonja Kristina

theartsdesk Q&A: Singer Sonja Kristina

Curved Air's frontwoman talks about their new album and her emotional musical journey

The March release of North Star, Curved Air's first studio album for 38 years, was no small triumph for vocalist Sonja Kristina and drummer Florian Pilkington-Miksa. Surging yet deliquescent, it echoes here and there the psychedelic pomp of the first three LPs they and original core members Francis Monkman and Darryl Way recorded at the height of the progressive rock era.

Sonja Kristina Linwood was a former folkie and a two-and-a-half year veteran of the stage musical Hair when, in January 1970, she joined violinist Way and keyboardist-guitarist Monkman's classically based group Sisyphus, which took its new name from Terry Riley's minimalist opus A Rainbow in Curved Air. Sonja Kristina sang with a crystalline clarity that transformed the band's shimmering melodies and sonic effusions into a spectral sound that anticipated Kate Bush and the Cocteau Twins.

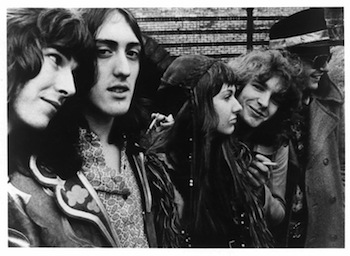

After Air Conditioning (1970), the masterpiece Second Album (1972), and Phantasmagoria (1972), Way and Monkman – unable to write together – left Curved Air, which had a revolving door of bassists. Because Sonja Kristina was able to enlist another virtuoso in violinist-keyboardist Eddie Jobson and guitarist Kirby Gregory, both under 20, Curved Air sustained its electrical charge on Air Cut (1973), the standout track "Metamorphosis" as potent as Way's "Vivaldi" and Monkman's "Piece of Mind." (Below, Curved Air 1971: from l., Pilkington-Miksa, bassist Ian Eyre, Sonja, Way, Monkman.)

When Jobson and Kirby quit, Way and Monkman returned for a tour that produced 1975's comparatively raucous Curved Air Live. Way stayed for Midnight Wire (1975) and Airborne (1976), but these were generic rock albums devoid of their predecessors' ethereal beauty. Sonja Kristina married the group's latest drummer Stewart Copeland, who co-founded the Police in 1977. "I then became a rock wife and polo widow and had two sons before resuming my career and separating from Stewart," she said in 2008.

Ever alert to new music, or old music in new forms, she duly cut a series of albums in different genres – experimenting with acid folk, jazz standards, and ambient – and writing revelatory lyrics about love, intimacy, loss, and motherhood. She reformed Curved Air in 2008 with Way, Pilkington-Miksa, bassist Chris Harris and, fleetingly, Monkman, whose desire to jam Grateful Dead-style wouldn’t mesh with Way's perfectionism. Unwilling to tour, Way left in 2009. Sonja Kristina recruited keyboardist Robert Norton and violinist Paul Sax from her 1990s acid folk group. Kirby returned to the fold when ill-health forced guitarist-composer Kit Morgan to bow out just before the recording of North Star.

Perhaps more solid in shape than ever before, Curved Air winds up its current tour tonight at the Cheese and Grain in Frome, Somerset; more dates follow in October. "Backstreet Luv" – a number 4 hit in 1971 – lives!

GRAHAM FULLER: North Star is reminiscent of Air Cut, the only previous Curved Air album Kirby played on throughout, but some songs recall the first three albums.

SONJA KRISTINA: Good. I'm not a musician in the same way Darryl [Way] and Francis [Monkman] are. I didn't go to music college and learn about time signatures. My way of approaching music is to let people play freely around my songs, which are influenced by whatever's around me at the time. I can't write Curved Air music – except for "Melinda More or Less" kind of things – but I did write the lyrics, except for Francis's "Piece of Mind" and "Over and Above". So on North Star I needed the musicality to come from the band. Robert [Norton] and Paul [Sax] and I had developed some stuff in 2012, some of which ended up in "Spider", and then they and Kit [Morgan] and Chris [Harris] presented ideas. Everybody brought in their own lines and melodies. From the bare bones they gave me, I chose the pieces that I could imagine being played on a stage at a big festival, that had grandeur and excitement.

What's your lyric-writing process?

I'm not prolific, but I had to have surgery last year and while I was recuperating the lyrics to "Time Games" and "Magnetism" came floating out – maybe it was the pills. I sang them very roughly on my phone and texted them to Paul and Robert. I also made a start on "Old Town News." "Images and Signs" evolved later in rehearsals. Some of the lyrics from "Time Games" were from a dream.

We had already started on "Stay Human" together. I had been immersed in the energy of the Arab Spring and I thought there had to be a song in it. I had this image of a woman and her lover. The man has joined the revolution, which is frightening because so much anger comes with change and can build into hatred that can last for generations. I've always believed the microcosm is reflected in the macrocosm so the energy in a relationship transmits to the outside world.

"Images and Signs" could be read as a critique of a couple filtering their love through technology. When you sing "intimate meanings on delicate ground," your voice deepens and the words become sinister.

I've had experience of a relationship where we were happiest communicating through e-mails and texts when we weren't together. During that tentative dance of attraction, the words and photos gain extra power and you weave a fantasy. It can be very creative in terms of expressing your feelings. (Below, Curved Air 2014: with violinist Paul Sax and bassist Chris Harris.)

Isn’t it also dangerous because the reality can't always live up to the reality?

But the fantasy is the important thing – that's the joy, the pleasure.

Did you call up Stewart [Copeland] and ask for permission to do the Police's "Spirits in the Material World"?

Nope. Someone suggested it would be good to cover a Police song. In terms of my lyrical thread, "Spirits in the Material World" fitted well. I decided to sing it quite ethereally. It takes a step back from the Police's reggae, though it has some of that feel. Kirby brought an extra energy to it. It had a '60s Flamingo Club vibe at one stage, but then it sparked up into a modern ska sound.

You also cover the Beatles' "Across the Universe".

I'd done a version of it at a little festival in Camden Town called "War, What Is It Good For?" with Robert, Paul, and Paul Hankin [percussionist] of the Ozric Tentacles. We also did Buffy Sainte-Marie's "Universal Soldier" and "Citadel" [from 1991's "Songs From the Acid Folk"]. Doing covers for North Star, I didn’t want to do them the way people are used to hearing them but just take the content and make it work.

I've had, when walking by the sea and looking at the sky under the influence of psychedelic substances, a sense of the stars singing and a wonderful vibration in the air – the vibration of existence, I suppose. For "Across the Universe", I had the concept of a tiny voice of peace in the middle of the universe. When we recorded it, I just sang it and Robert played in the moment.

You revisited three early Curved Air songs on the album – "Situations" [from Air Conditioning] and "Puppets" and "Young Mother" [from Second Album]. It's been rumored that "Young Mother" was inspired by Jackie Kennedy. Is that true?

No, it has nothing to do with her. It's just about being strong and kind, which was my philosophy of life at the time we originally recorded it and probably still is now. Darryl wrote it first. His original words were "Young mother in style/Trying hard to keep her smile." Those words are actually on what is now Air Waves [2012], the re-mastered BBC John Peel sessions. I just never settled into that version, so I got into the melody and stretched it and played the chords on the piano and sang over it. Then I came up with the words and the tune, and it moved me, which was great – so then it moved other people, too.

I've long been haunted by your recitation of the lines from T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land" in "Piece of Mind". How did they end up in there?

Francis stuck them in. "Piece of Mind" was entirely his own work. Like a great composer, he could just play a composition on a keyboard and know exactly who would play the different parts. That song is about being in a mental hospital. I think the Eliot lines just provide a bit of mood.

It’s one of those eerie Curved Air songs, full of phantoms.

There's a lot of them! Francis's phantoms – they're his own – are all over Phantasmagoria. "Over and Above" is a beautiful song – "One fine night I left my soul to journey on the wind/Far beyond the stars I watched to see where it would go." I can feel that when I sing it. Francis also wrote "Everdance" [on Second Album] as well, but Phantasmagoria was the real ghost album.

Though it's made up of demos, Lovechild [1973, released 1990] features one of your most powerful songs, "Seasons". Does it still resonate with you?

The lyrics are nice. It's not something I'd want to do now because it's too static, though maybe it would work with more stripped-down music, just keyboards or something to give it room to breathe.

In the mid-1970s, Curved Air's sound and image became more raw and sexual. Certainly, your singing was less ethereal on Midnight Wire and Airborne.

I'd heard Janis Joplin for the first time when we were in America and was very moved by her – I don't know if that was an influence. I went through some personal problems at that time. Between Air Cut and the live album, my marriage to Mal Ross, who used to be Black Sabbath's tour manager, broke up, so I was going out and partying a lot and drowning my sorrows with various kinds of inebriation. The original Curved Air members had gone off to do their own things. Then I got the Air Cut band together and they went off, too, which left just me. I did some recordings that were apparently turned down by the record company and the management cut off my money. I had a son to support so I went out to work and got a job dealing cards in the Playboy Club. I ended up back in the same Hampstead flat where I used to live with the original Curved Air. I was living with this lady, Norma Tager, who ended up writing the lyrics because I just didn't want to write anything.

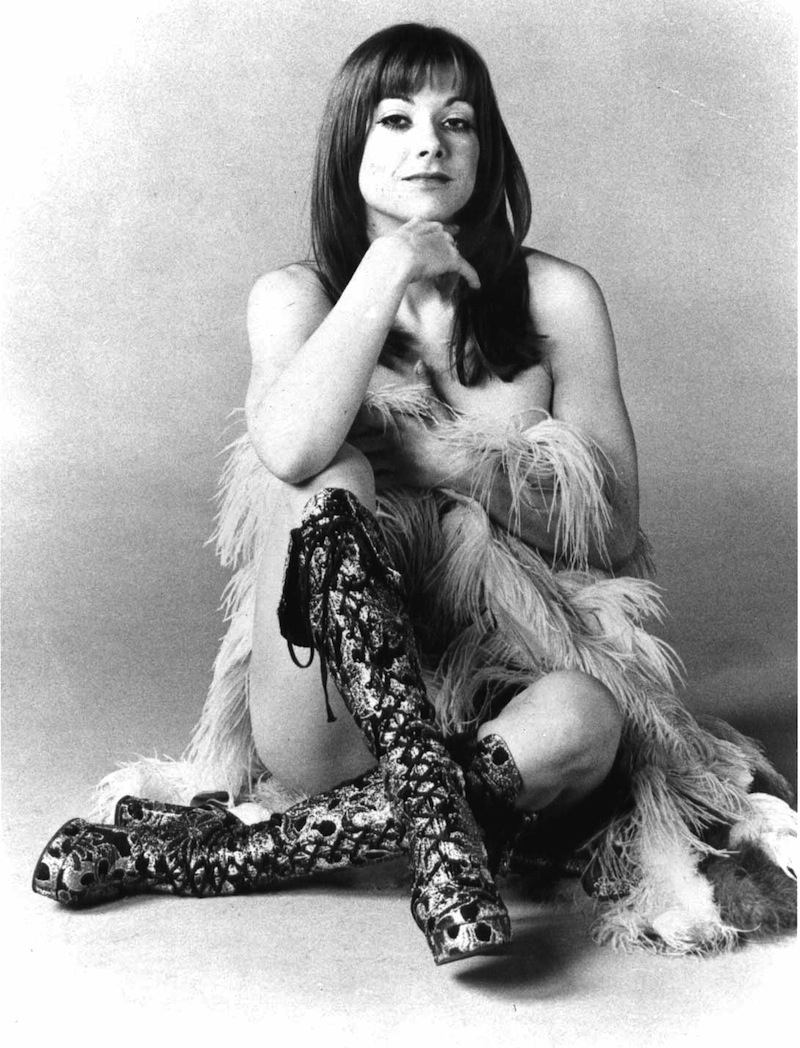

I was drinking before the shows we did then and would be wired. I went for it with abandon, which I hadn't done before. Because I'd worked at the Playboy Club, I didn't see anything wrong with going on stage almost naked, slightly veiled with a bit of lace and stuff. I had never been so overtly feminine with Curved Air in the past. I was a kind of space gypsy, something from somewhere out there, not like a normal showgirl. We had fun buying fabrics from the market and making new costumes to create this glamorous, ragged, tatty look (pictured above). The clothes I wear now are just a more mature version of that.

I don't know if Marvel Comics's Red Sonja came out of that image, but I remember the artist [Barry Windsor-Smith] being in our dressing room at the Roundhouse one time and that I left him a note….

Curved Air then went into a long hiatus and you formed Escape.

That was liberating. I cut my hair. I was inspired by punk. I liked that everyone was a character – an anarchic human installation.

That led to your first solo album [Sonja Kristina, 1980], which had a much more pared-down sound.

That album was my version of Curved Air punkified, I think. "Street Run" was based on the Notting Hill Riots. I was there and remember the sound of the crowd changing from a happy burble into the roar of some beast. It got all mixed up in my head with my memories of growing up in a boys' approved school where my father was the headmaster. From birth to 18, the backdrop in my life was 16-year-old delinquent boys.

In the 1990s and 2000s, you embarked on an eclectic period of experimentation. First, you revisited your folk beginnings with Songs From the Acid Folk and then Harmonics of Love [1995], which is full of the sounds of nature.

I was echoing what was around me. We called it "astro-folk", as opposed to "acid folk". It was a kind of leaning into folky trance music.

Was that period rewarding?

On my fortieth birthday, I was in heaven because I was playing acid folk, with all its ingredients, at the Crypt in Deptford. But when I was doing the Acid Folk album, Stewart and I were going in different directions. I left him and lived with Graeme [Holdaway], who'd produced the record. We had a nice relationship for five years, then he suddenly went off to find himself. I'm still friends with him – as I am with Stewart – but at the time it was a big shock to my system. (Below: covering David Bowie's "Sound and Vision" on MASK: Technopia, 2009.)

And that led indirectly to Cri de Coeur [2003], your non-jazz album of jazz standards.

I had an obligation to stand by my sons [Sven from an earlier relationship; Jordan and Scott from her relationship with Copeland], taking care of their schooling and everything, and all my creativity left me. But then I started doing vocal coaching and was offered a job teaching rock and pop voice at Middlesex University. They told me I'd have to teach jazz, too. I thought, "Oh my God, what is jazz?" During the six years I was there, I sorted out what I did and didn't like about it, and, as a step into writing again, I took some of the songs I liked and recorded them with spare arrangements, just piano, bass, flute, and saxophone. I'd also been inspired by Angelo Badalamenti's soundtracks, especially the one for The Straight Story, which was country music recorded live but with a weird, cinema tension-making background to it.

A year earlier, I'd been helping someone find artists for an online record label and came across Marvin Ayers's music, which I thought very exciting. He came to hear me singing the Cri de Coeur songs just before we went into the studio and said how much they suited my voice. I thought, "I need his sound" – he made these dissonant pieces, some more melodic, with evolving waves of strings – and we produced the record together. Then he said he'd like to work with me on something different.

It seems we had history. When he was a 15-year-old, he had been best friends of a girl called Hazel, the only female fan who actually came to the Curved Air house to my knowledge. She was a beautiful David Bowie-lookalike with red hair. Apparently, they came to the studio when we were recording Air Cut or Lovechild.

Under the name of MASK, you and Marvin made two ambient albums [Heavy Petal, 2005, and Technopia, 2009] that blended electronica and classical.

It was a whole new world, though I'd experimented with trancey, droney ambience and sound loops on Harmonics of Love. When Marvin and I were improvising, I was inspired to write again and it was another period of great fertility. Marvin knew all about music as art – not like techno, which is music to dance to, but music as a background to alternate realities. I don't think we'll do more together but for me it was very enriching.

Back to Curved Air – do you plan to record again?

Not in a hurry. With Kit leaving just when we started recording and Kirby coming in, we had to re-examine all the ideas and we had to challenge each other – it was quite volatile at times, but we kept coming back to the task and worked through a very stressful year. Everyone says the music is right for who we are and that it's right for the Curved Air name. Yes, we will do more recording, but it has to be beautiful.

I wondered if the title of North Star was a tribute to Sandy Denny's The North Star Grassman and the Ravens?

Not at all, though I love Sandy Denny. In the 2000s, I moved from North London and lived on North Street in Clapham. My children had left home and it was a new start in a new environment. I just like the idea of North Star as a guiding light. We know where we are at this moment in time because of the positions of the stars. It's all very cosmic really.

Below: Curved Air's "Backstreet Luv," 1971.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Comments

Was Desiree plagiarized by