The Dark Side of the Moon: Introducing Prog | reviews, news & interviews

The Dark Side of the Moon: Introducing Prog

The Dark Side of the Moon: Introducing Prog

The first in a series celebrating the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd's masterwork

In 1973 certain world events carved themselves, a bit like the faces on Mount Rushmore, deep into the landscape of the late 20th century. No sooner had Richard Nixon begun to end the Vietnam War than Watergate broke. In the autumn Allende was overthrown by Pinochet in Chile; Egypt and Syria’s attack on Israel ignited the Yom Kippur war. A global oil crisis was to leave western economies strapped.

In Britain industrial unrest forced a tottering Heath government towards the Three Day Week. The IRA began bombing London. It wasn’t, really, a happy epoch; but young, mainly male, slightly self-fancying British musicians were, as was their wont, ignoring all that, perhaps even (to twist Paul McCartney’s lyric of five years before) taking bad times and making them better, or trying to, on vinyl.

The wildness was musical, not behaviourial

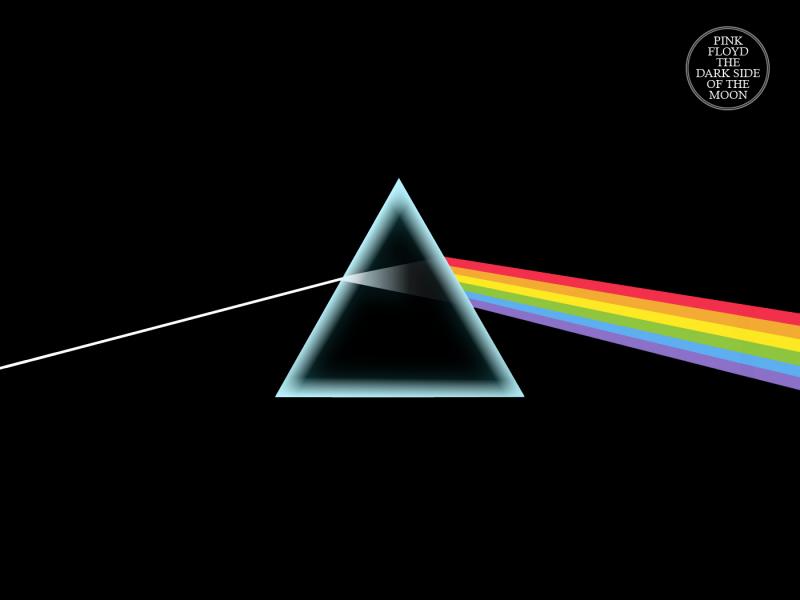

That’s what good pop and rock of the era did: got you high and helped you escape, perhaps the latter above all. A new “seriousness” also loomed. In March the invasion into teenage minds of a black-sleeved LP bright with echoey footsteps, male cackling, tick-tocks, chimes, a preoccupation with madness and alienation and, on its two sides, sonic spaciousness marked if not the start of then a major staging-post in this much derided thing called progressive rock. The Dark Side of the Moon seemed mysteriously to register some of the more dysfunctional things going on in the world, but it was a delicious listen too.

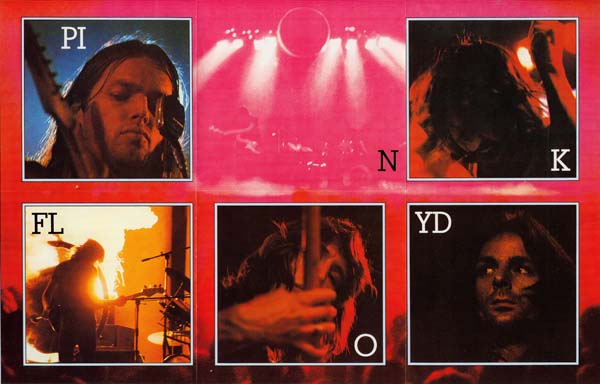

For some it came from nowhere. But Pink Floyd (pictured right, clockwise: David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Rick Wright and Roger Waters on Dark Side's original poster) had already put down formidable traces as one of the wilder psychedelic combos of the late 1960s. The wildness was musical, not behaviourial: by Dark Side group founder Syd Barrett had quite lost the plot through chemical self-immolation. Post-Barrett albums such as Ummagumma (1969), Atom Heart Mother (1970) and Meddle (1971) evinced a donnish disregard for pure, witty song-making - Barrett’s forte - and are full of prickly, experimental atmospherics.

For some it came from nowhere. But Pink Floyd (pictured right, clockwise: David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Rick Wright and Roger Waters on Dark Side's original poster) had already put down formidable traces as one of the wilder psychedelic combos of the late 1960s. The wildness was musical, not behaviourial: by Dark Side group founder Syd Barrett had quite lost the plot through chemical self-immolation. Post-Barrett albums such as Ummagumma (1969), Atom Heart Mother (1970) and Meddle (1971) evinced a donnish disregard for pure, witty song-making - Barrett’s forte - and are full of prickly, experimental atmospherics.

Then, somehow on The Dark Side of the Moon, Roger, David, Rick and Nick (no, the names of this quartet never quite tripped off the tongue) brilliantly united the best of their aural objets trouvés with a rock insistence, coolness and gravitas combined. Millions and millions wanted to buy it, and did.

Pink Floyd were not lone innovators. 1973 was as it happens a fantastically rich British year. A music culture producing within 12 calendar months a teenage soloist’s multi-instrumental, monster-selling album (Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells) - launching the career of a hippie businessman (Richard Branson) - a debut LP by a camp foursome fronted by a buck-toothed Zanzibarian (Queen; Freddie Mercury) and a two-record rock opera by a seminal 1960s noisemaker (Quadrophenia; The Who) can only be called, well, big.

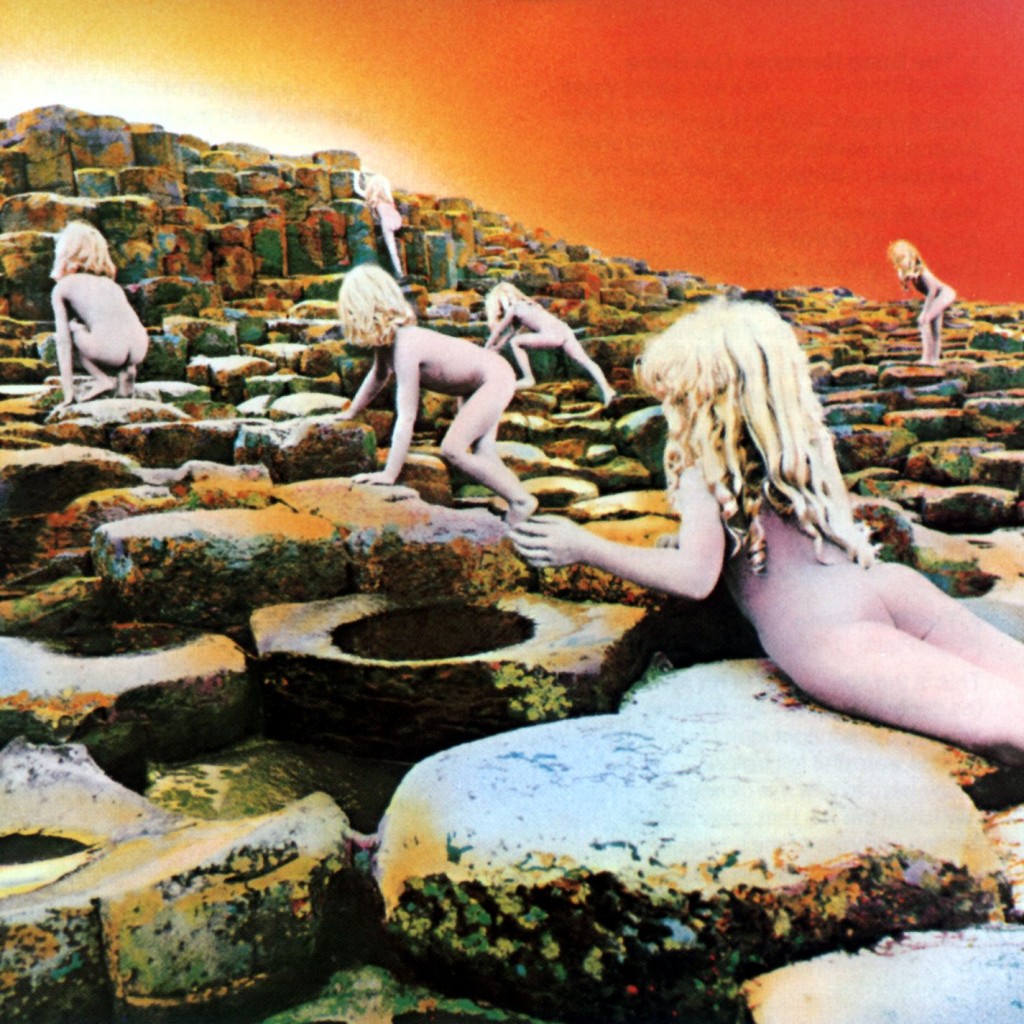

Big ideas, and very big sounds, were to roar from our isles across the western hemisphere in 1973. If the year was anybody’s it was Led Zeppelin’s. Kicking off with the quasi-sonata, and very prog, “The Song Remains the Same”, Houses of the Holy (pictured left) appeared mere weeks after Dark Side, and was then trumpeted in an enormo-tour of the US; Zeppelin were the first, that summer, to break a Beatles gig-attendance record there. Though fiercer, certainly more Moët-guzzling than feyer British outfits like Jethro Tull, or more pompous ones like Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and so not conventionally of the progressive camp, Led Zeppelin became increasingly sophisticated - highly, sculpturally sharpened in their musical thinking - from the Houses period through to their rock monument of 1975, Physical Graffiti.

Big ideas, and very big sounds, were to roar from our isles across the western hemisphere in 1973. If the year was anybody’s it was Led Zeppelin’s. Kicking off with the quasi-sonata, and very prog, “The Song Remains the Same”, Houses of the Holy (pictured left) appeared mere weeks after Dark Side, and was then trumpeted in an enormo-tour of the US; Zeppelin were the first, that summer, to break a Beatles gig-attendance record there. Though fiercer, certainly more Moët-guzzling than feyer British outfits like Jethro Tull, or more pompous ones like Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and so not conventionally of the progressive camp, Led Zeppelin became increasingly sophisticated - highly, sculpturally sharpened in their musical thinking - from the Houses period through to their rock monument of 1975, Physical Graffiti.

For British bands of this stripe the US was key. Its vast territory was where unit sales were implacably notched up (and still are, or can be). Touring there fed an extraordinary appetite in young Americans for this musical stretching towards immensity. So it was for a band to which many still say “no”, Yes. Yes were very, very big in America. It’s just a shame the release of their eternally vilified, otiose Tales from Topographic Oceans at that year’s end has effectively cast into outer darkness five talented musicians’ dense and expert performances on Fragile (1971) and Close to the Edge (1972) - the essence, love them or hate them, of prog.

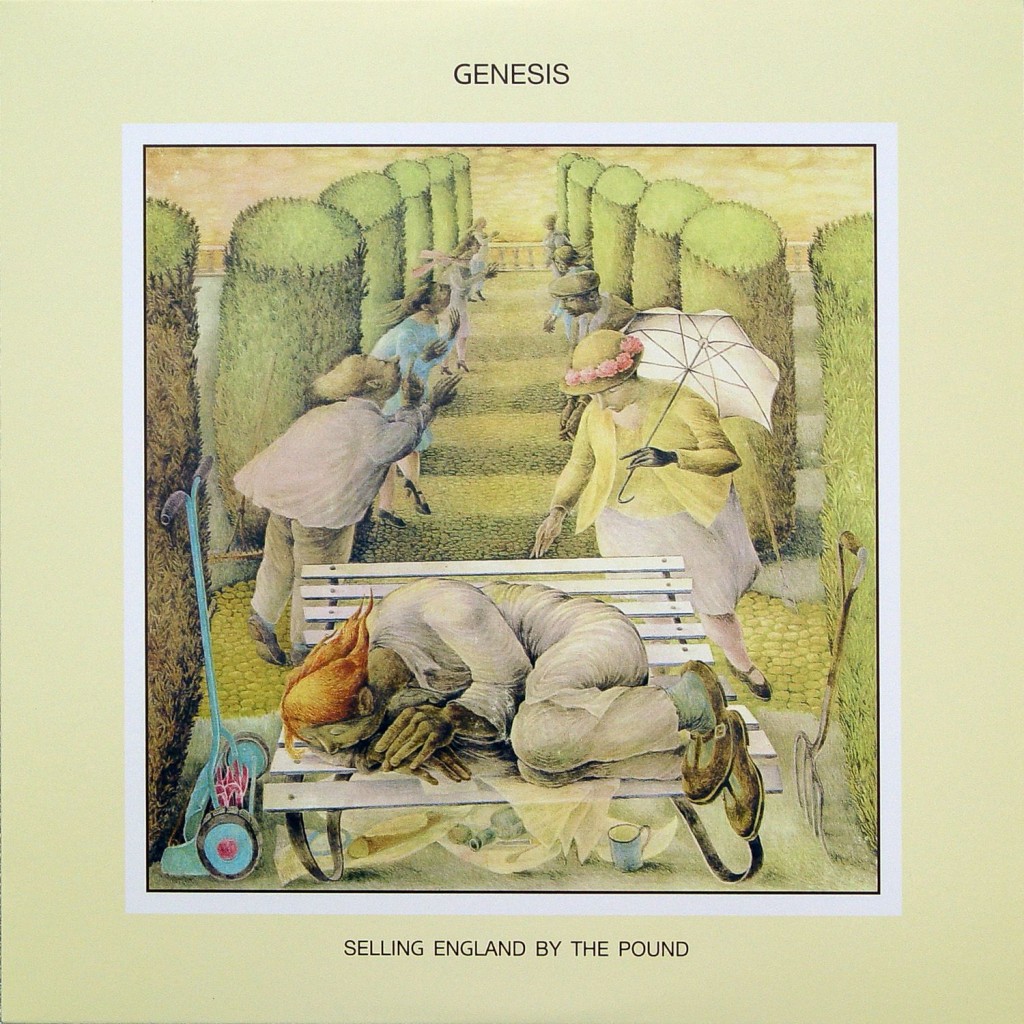

Then there was Peter Gabriel’s Genesis. Selling England by the Pound (pictured right) was released in 1973. Only the following year’s The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway cut much ice on tour in the US - Gabriel then quit - but this most self-ironising of English bands found their truest voice on this record. Its quipping and word play, surreal poetry and instrumental adventurousness make it (arguably) as fresh today as 40 years ago. Even Phil Collins sang a very pretty song on it.

Then there was Peter Gabriel’s Genesis. Selling England by the Pound (pictured right) was released in 1973. Only the following year’s The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway cut much ice on tour in the US - Gabriel then quit - but this most self-ironising of English bands found their truest voice on this record. Its quipping and word play, surreal poetry and instrumental adventurousness make it (arguably) as fresh today as 40 years ago. Even Phil Collins sang a very pretty song on it.

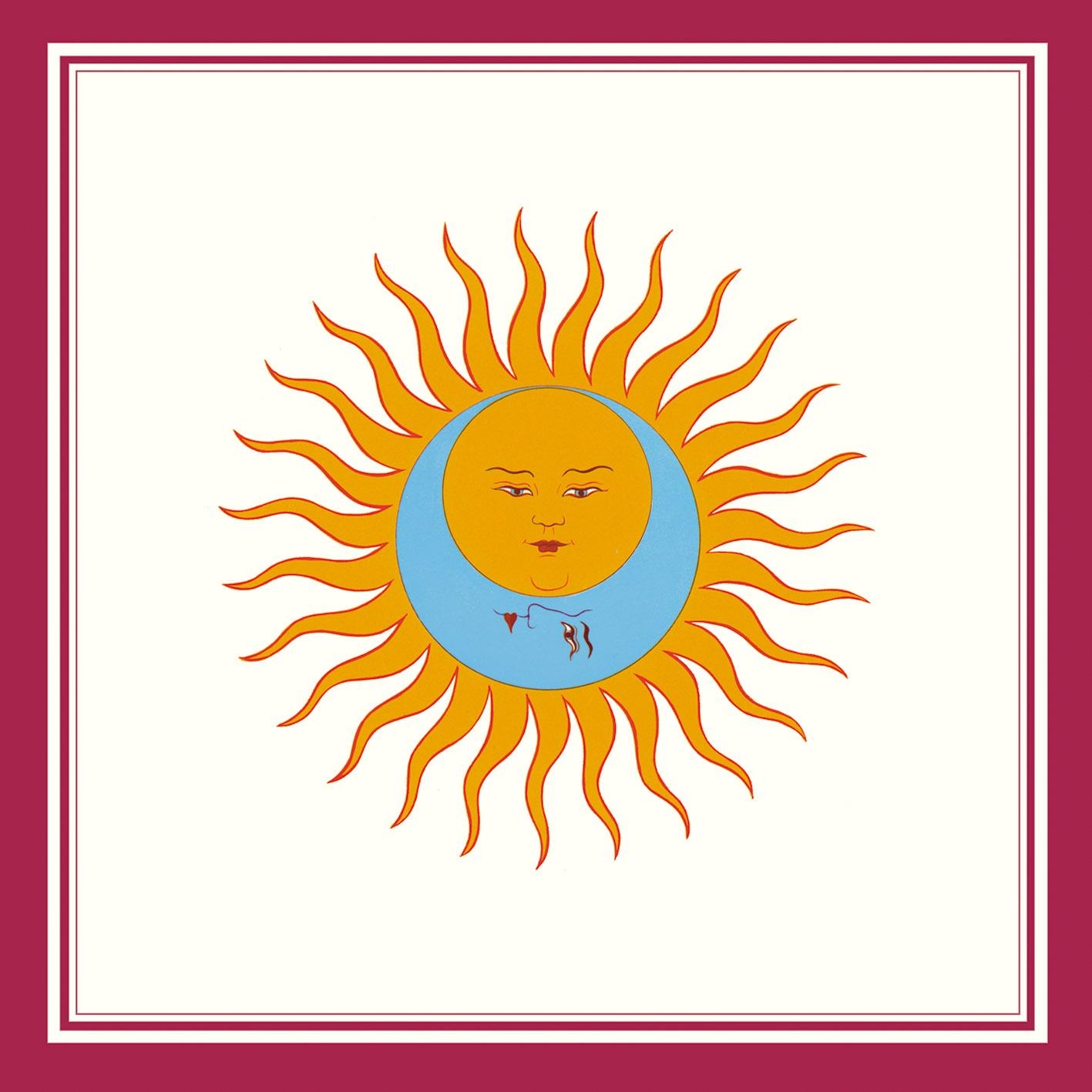

These things are, finally, about taste. Pink Floyd were unignorable but not especially likeable; their music could be monotonous. King Crimson have remained, like Yes, somewhat in the vilification stable of prog - pretentious, endlessly, nerdily noodling - but for my money, in a trilogy of albums begun in 1973, they remain the best: an essential of the genre. Shaped compositionally by a preternaturally gifted lead guitarist, Robert Fripp, Larks’ Tongues in Aspic (pictured below), Starless and Bible Black and Red (the latter two recorded in 1974) are exercises in sheer attack, rhythmic danger, textural polyvalence and lyric bravery. Jazz and scorched minimalism pulse through each. The eponymous track of the middle album remains the most fascinatingly frightening 10 minutes in rock.

The adventure wasn’t, of course, to last. By the time of Pink Floyd’s next LP in 1975, Wish You Were Here, a pale youth, surname Lydon, had started to hang around Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Chelsea boutique SEX. His T-shirt screamed “I Hate Pink Floyd”. Johnny Rotten was in the wings. Punk would do for prog. All said, though, a small guess: more people across the world today, many more, pep themselves up in the morning, or relax at night, or have a nice smoke, to “Breathe” than “Holidays in the Sun”…

The adventure wasn’t, of course, to last. By the time of Pink Floyd’s next LP in 1975, Wish You Were Here, a pale youth, surname Lydon, had started to hang around Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s Chelsea boutique SEX. His T-shirt screamed “I Hate Pink Floyd”. Johnny Rotten was in the wings. Punk would do for prog. All said, though, a small guess: more people across the world today, many more, pep themselves up in the morning, or relax at night, or have a nice smoke, to “Breathe” than “Holidays in the Sun”…

More pieces on The Dark Side of the Moon follow on theartsdesk through the week

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Add comment