The Dark Side of the Moon: Prog’s Gleaming Peak | reviews, news & interviews

The Dark Side of the Moon: Prog’s Gleaming Peak

The Dark Side of the Moon: Prog’s Gleaming Peak

Concluding theartsdesk's 40th-anniversary celebration of Pink Floyd's opus

Let us go now to a foreign country. To the foreboding concrete tunnels and rooms of an RAF early-warning facility under the Sussex Downs in the early summer of 1973.The Lower Sixth has somehow procured the space for an epic late-night party. Cheap beer and cheaper cider is drunk. Cigarettes are smoked, self-consciously. Flared jeans and cheesecloth shirts are worn under Afghan coats, not with panache.

There’s no dancing because there’s no DJ and no one has thought to bring any pop singles. Instead, there’s a pile of gatefold-sleeved albums beside the record player, each of which gets played to completion or until someone gets bored. Since you can’t dance to LPs like King Crimson’s In the Wake of Poseidon or The Yes Album, people stand and talk in small groups, the sexes mostly divided.

Tubular Bells has just come out, but it’s too cerebrally tintinnabulous for a party in this Cold War redoubt. Aladdin Sane is new, too, but most of us are still wary of Bowie’s androgyny. The anthemic highlight of the evening is The Dark Side of the Moon. The first thuds of the opening heartbeat melt the frigid atmosphere. There’s a small terrace by the wall, and nearly everyone sits on it to listen to Pink Floyd’s epochal record.

Disappointed the Floyd hasn’t produced another hallucinatory opus like the Atom Heart Mother suite or Echoes, I had initially resisted DSOTM, sceptical of its consecutive song structure. Why would they jettison such ethereally beautiful symphonic rock? But the LP gradually put its hooks into me, and they’ve never fallen out. Even if its messages and melodies seem sadder with the passing years, you can still apply old Melody Maker adjectives like “majestic” and “haunting” to it without the triteness-police nabbing you. The future belonged to The Clash and Joy Division, but DSOTM was prog’s gleaming pinnacle. (Pictured above from left, Nick Mason, Dave Gilmour, Roger Waters, Rick Wright.)

Preceded by Meddle and followed by Wish You Were Here, it was the undisputed masterpiece among the three great Floyd albums, after which there was a tailing off until the final resurgence with The Division Bell. In terms of the evolution of sophisticated British rock, it was the link between Sgt. Pepper and OK Computer. Radiohead may resent the comparison, but DSOTM set the benchmark for sonically layered tunes that radiated existential despair.

Back on the steps, we hear those two guys talking about being mad for fucking years and those unearthly screams – uttered, presumably, by a mother giving birth. Dave Gilmour’s relaxed, bluesy slide guitar groove takes over. The sound is big, cinematic, inclusive. We nod our heads in tune to it. We breathe in the air and we’re not afraid to care. There’s still no dancing, but boys and girls are mingling now, and some pair off. The point is that Pink Floyd’s songs of everyday English dystopia – built on drudgery, boredom, inequality, and greed, wracked by the fear of madness and death – have united the people in the concrete room.

“Breathe” gives way to the synthesised air-travel nightmare of “On the Run”, which ends in disaster. "Time"'s Orwellian cacophony of antique alarm clocks follows. The mood has changed and Gilmour’s singing is hectoring. When Rick Wright takes over to sing the two bridges, he sounds spent, resigned. The lyric “Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way” captures the ennui into which the song has drifted.

“Breathe” gives way to the synthesised air-travel nightmare of “On the Run”, which ends in disaster. "Time"'s Orwellian cacophony of antique alarm clocks follows. The mood has changed and Gilmour’s singing is hectoring. When Rick Wright takes over to sing the two bridges, he sounds spent, resigned. The lyric “Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way” captures the ennui into which the song has drifted.

When you’re 17 those words don’t resonate as much as “I hope I die before I get old” or “I am an anti-Christ”. But as you listen to DSOTM as you age, they become increasingly poignant. Gilmour had been singing about the danger of wasting time, but since his words weren’t heeded, the procrastinators he was addressing have frittered their lives away so completely that they now have only a faint grip on reality. “Hanging on” may be a commonplace for stoicism, but the metaphor must have originated in the terror of someone whose grip on a cliff-edge is loosening.

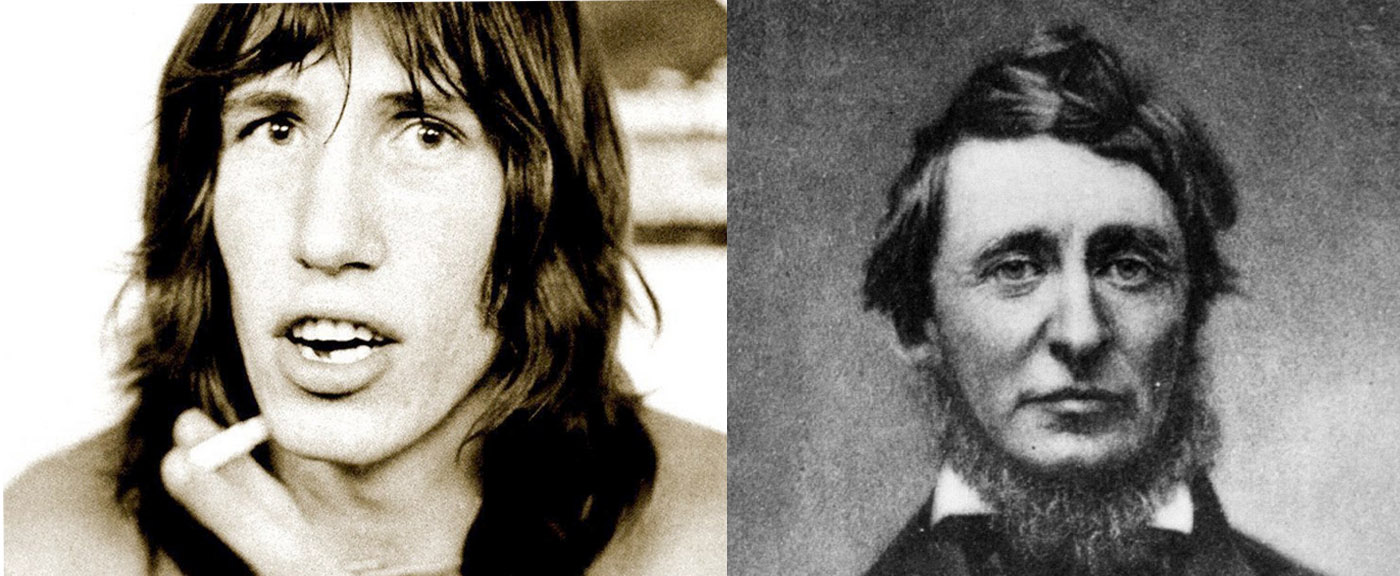

The lyrics of “Time” were written by Roger Waters, Pink Floyd’s least forgiving observer of human folly. “Hanging on in quiet desperation is the English way/The time is gone, the song is over/Thought I’d something more to say” echoes Henry David Thoreau’s words in “Walden” (1854): “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.” Waters has said that “quiet desperation” seemed the best way to sum up the English (Waters and Thoreau, top of page). The phrase supports a notion of endurance that’s less reassuring than the myth of stiff upper lip-dom. “Desperation” skews the sentiment away from the World War II ethos of keeping calm and carrying on toward barely withheld panic (above: Ian Emes's animated film for "Time".)

Two things happen that save “Time” from cynicism. Gilmour’s massive searing riff can be interpreted as a rebuke to people who throw their lives away, but as it draws to a close, it softens and curls into a tender embrace. Then, as the song segues into “Breathe (Reprise)", he sings of the simple comfort (improbable though it seems, but he's only human) of warming his bones beside the fire when he comes home cold and tired. These lines come next: “Far away across the field/The tolling of the iron bell/Calls the faithful to their knees/To hear the softly spoken magic spells". Is Waters being ironic here? I don’t think so. Gilmour sings the words devotedly, as if he accepts the need for spiritual balm.

Some of the sixth formers at the party in the RAF place are dead now. I have kept in touch with two or three only, so I really don’t know who has settled into comfortable middle age and who is hanging on with quiet desperation. I do know that these words from “High Hopes,” the last song on “The Division Bell,” convey what the memory means to me:

The grass was greener

The light was brighter

With friends surrounded

The nights of wonder.

Read about The Dark Side of the Moon on theartsdesk

Pink Floyd perform 'Time' at Earls Court, 1994 (from the Pulse DVD)

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Add comment