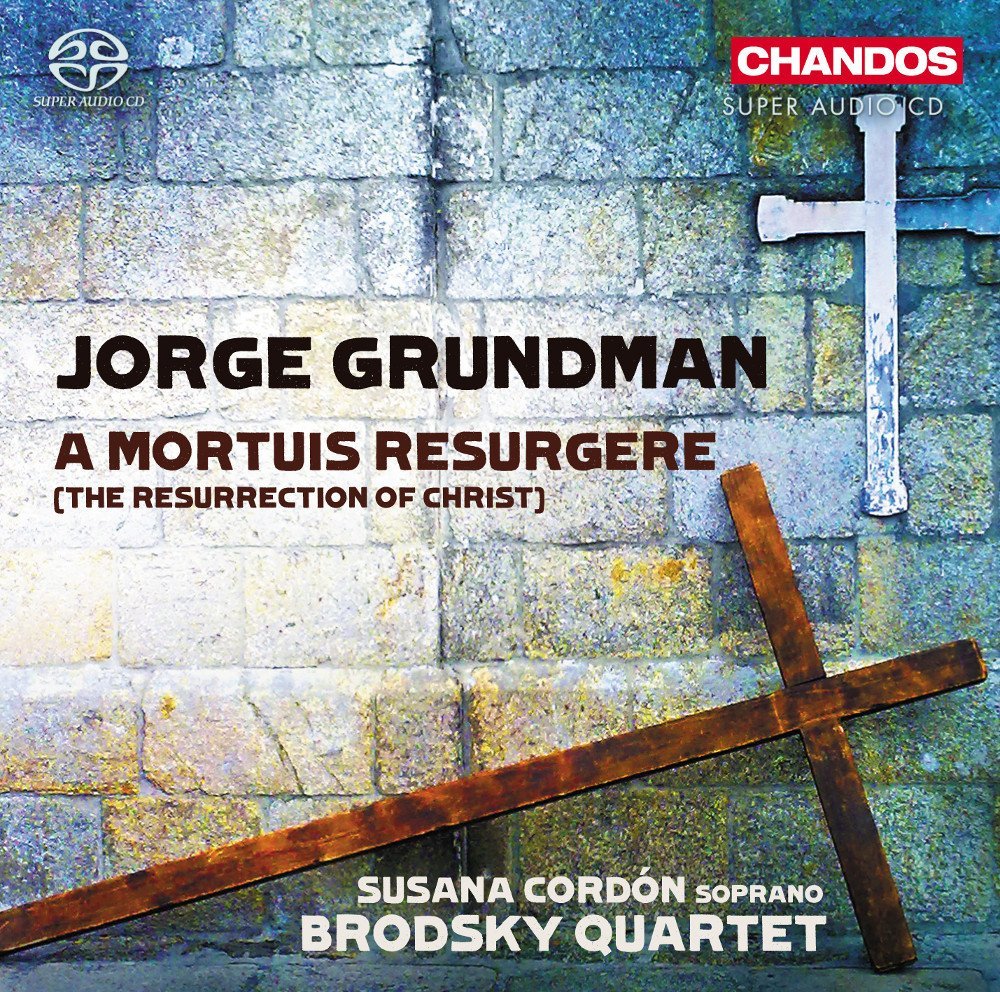

Spanish composer Jorge Grundman was a vocalist and keyboard player in two bands in his teens, and he’s now a professor of audio engineering at a Madrid university. His website includes this disarming statement: “I consider myself a writer of music more than a composer. I just try to tell stories through the music narrative. I do this in the simplest, almost naive way possible. I want people to find my music sentimental and moving and also, as far as possible, to fancy listening to it again.” I read those phrases and steeled myself in expectation of something embarrassingly banal and simplistic, but was quickly won over – as with the likes of Arvo Pärt, writing readily accessible music needn’t involve any dumbing down. Fifty-five minutes of stately, major-key radiance pass in the blink of an eye. I’ve listened to this disc three times so far, and I’ll be returning to it again.A Mortuis Resurgere is a string quartet and soprano follow-up to Haydn’s Seven Last Words of Christ, the Resurrection retold using Latin verses taken from the Gospel of St John.

Everything unfolds at a Brucknerian pace, with good reason – Grundman conceived the work for church performance, the slowness of movement accommodating the increased reverberation. Susana Cordón’s soprano line unfolds with calm authority and clear diction, repeated listenings revealing just how her singing reflects what’s happening in the narrative. The relative lack of musical incident is never a problem, making the occasional changes of tack more surprising and effective, as with the more animated quartet writing accompanying the closing Hosanna. Beguiling, emotionally charged music, sensitively performed and beautifully recorded.

New recordings of this extraordinary piece are still an event. Leonard Bernstein conducted the first performance in 1949, and it’s nice to think that he would have gloried in Messiaen’s extrovert sensuality. So much postwar music is, with reason, dour, gritty and grey. Turangalîla’s confidence and positivity must have come as a shock. Successful performances don’t downplay the vulgarity. A favourite recording remains Previn’s 1970s account with a rowdy LSO, where at one point you can hear a percussionist stifling giggles after a loud bass drum thwack. There’s a lot of humour in this baggy 10-movement work. Take it too seriously and the message gets lost. Hannu Lintu’s live version with Finnish Radio forces has much to commend it. He’s wonderful at observing what’s going on at a micro level, especially the insectile scratchings and tickings which make up much of Messiaen’s percussion writing. Hearing the various layers so clearly is a delight – there’s a great example five minutes into the first movement, with percussion ostinati, piano and strings, each going in a different direction, each perfectly audible.

Lintu's trump card is having Angela Hewitt to tackle the concertante piano role. Her playing is vibrant and clear, less hazily impressionist than can be the case in this work. The big cadenza in the fourth section is a stunner, as is its dreamy, bluesy comedown. She’s nicely partnered by Valérie Hartmann-Claverie on ondes martenot. The instrument’s sound is brilliantly caught by Ondine’s engineers, allowing us to hear the seismic grunts and groans it can make in its lower register. What I miss is the sense of abandon. Several of the earlier climaxes just aren’t fruity enough, as if all concerned are slightly embarrassed by Messiaen’s unhinged generosity of spirit. Things do warm up; "Jardin du sommeil d’amour" is all the better for moving at a flowing speed, and the "Développement d’amour" is more unbuttoned. But the final movement’s big chorale, though carefully coloured (with prominent ondes martenot), could be brassier and more exultant, the lurid last chord sustained for longer. Get this for Hewitt’s contribution. Ondine’s sound is stunningly natural, the widescreen stereo cinematic.

“Transcription can bring us to the music, and to its original hearers, afresh.” Hugh Collins Rice’s sleeve notes point out that we’re listening to the four pieces on this disc in a form which would have been familiar to fin de siècle audiences, for whom piano arrangements would have offered the only opportunity to experience much new music. Three movements from Stravinsky’s Firebird were transcribed in 1928 by Guido Agosti, and they’re a delight, bringing the harmonies into sharper focus and adding percussive glitter. The "Danse infernale" sounds not unlike Ravel, and it’s followed by the Berceuse and Finale. Aki Koruda’s introduction to the latter is wondrous, Stravinsky’s horn melody stealing in over an immaculately realised tremolando. Koruda follows it with an imaginative transcription of Debussy’s Prélude à l’aprés-midi d’un faune made by the English pianist Leonard Borwick. As with the Stravinsky, Debussy’s harmonies can be heard in sharper focus, though there’s no loss of poetry.

Rarer still is a piano version of Schoenberg’s quicksilver Chamber Symphony, transcribed by the composer’s pupil Edward Steuermann in 1920. Kuroda’s fearless precision pays huge dividends in such mercurial music, Schoenberg paying his respects to Mahler and Strauss as well as looking forward. It’s magnificent, and highly accessible. Japanese composer Yoichi Sugiyama's recent transcription of the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony is less successful. Mahler’s touching strings-and-harp original is transformed into something oppressively gloopy and overwrought, devoid of any light and shade.

Add comment