About 10 minutes into the Brahms Third Symphony I wanted to check a name in the Budapest Festival Orchestra’s programme. I dared to turn a page. Bad idea. Such preternatural stillness had settled over the sold-out Royal Albert Hall that the gesture could probably have been spotted from the balcony. A motionless, virtually breathless audience is a rarity even at the Proms, where quality of listening is venerated; still, to hold around 6000 people quite so rapt with attention is an extraordinary skill in orchestra and conductor. But then, the Budapest Festival Orchestra and Iván Fischer are no ordinary visitors.

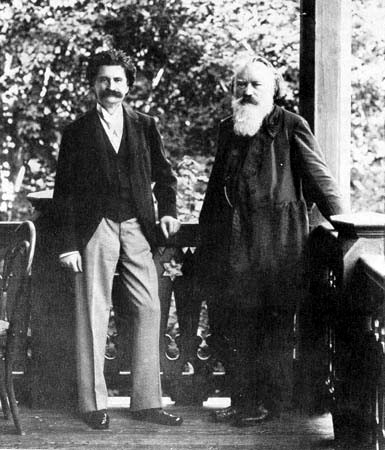

For this, the second of their two Proms, they chose total immersion in Brahms (pictured below with Johann Strauss II, featured in the first of the orchestra's Proms, on the left): the Third and Fourth Symphonies: a short but intense concert with musical marvels to be lapped up in every bar. The Third is the subtlest and most surprising of the four symphonies, sparked at the outset by a direct quotation from the equivalent symphony by the composer’s mentor, Schumann; in the latter it is a quiet, closing phrase, but Brahms elevates it into an impassioned, conflicted and uncompromising statement that, when played as it was here, contains a world of complex emotion. The Fourth Symphony is his last and most stringent statement in the form: reflective and sometimes austere in atmosphere, it is wrought with a perfectionism that gives it an iron-strong core. Its final Passacaglia takes no prisoners.

Much of the stillness in the hall can be attributed to Fischer himself. His conducting is tremendously centred, featuring an upright stance and great economy of gesture. Each movement is precise and focused – no histrionics here – and the orchestra is fine-tuned to his guidance, responding as one to the slightest twitch of a finger.

There is undoubtedly something uebercontrolled about this ethos: for instance the ensemble of the BFO’s string sections is second to none, so unified that they can sound like a giant string quartet. One sometimes feels Fischer keeps them on a tight rein, so sleek and polished is the sound, but there is opportunity aplenty for personal expression where it is needed; for instance, the first flute, Erika Sebok, brought heartrending beauty to the darkest, loneliest of solos in the Passacaglia of the Fourth Symphony.

There is undoubtedly something uebercontrolled about this ethos: for instance the ensemble of the BFO’s string sections is second to none, so unified that they can sound like a giant string quartet. One sometimes feels Fischer keeps them on a tight rein, so sleek and polished is the sound, but there is opportunity aplenty for personal expression where it is needed; for instance, the first flute, Erika Sebok, brought heartrending beauty to the darkest, loneliest of solos in the Passacaglia of the Fourth Symphony.

But that finesse, that close attunement to Fischer’s intent, is key to making the BFO’s performances a cut above the average competition. Fischer is an exceptional musician – he is also a composer, a skill that often adds to the ability to identify with musical processes from within during performance – and he reaches the details that can elude some others. Where the bigger picture is concerned, he thinks in long lines that give purpose and momentum to musical cause and effect, and one cannot imagine better-judged tempi or balance, which seemed perfect even in the RAH acoustic.

The double basses and timpani are ranged across the back, raised an extra level, while first and second violins are on opposite sides of the stage front – it works a treat. Within this inspiring whole there is a careful, supple sense of ebb and flow – a slight ritenuto on part of a phrase, a poise on a top note, or a swift catch-up of rubato – that would not be possible to this degree with a less focused ensemble. Furthermore, Fischer can imbue a phrase with the essence of its purpose, transforming emotion or sensation straight into the detail of the sound.

The fact that most of the BFO players are Hungarian (most - I spotted one Irish name on the list for their other concert) and share a very specific musical heritage and training certainly does not hurt. This is not necessarily a magic formula by definition, of course, and the importance of extremely hard work shouldn’t be overlooked. But where it may have paid off is, ironically, in the encore. Fischer announced that they would perform Brahms’s ‘Abendständchen’ (Evening Serenade) – and the players promptly put down their instruments, formed themselves into a choir and sang, a cappella. Singing is the foundation of Kodály-based Hungarian musical training (or would have been for most of these players in their childhood) – every child would have learned to sing before learning to play – and the orchestra made the transition seamlessly. Let’s get one of the London orchestras to try it next time.

Add comment