Down by Law | reviews, news & interviews

Down by Law

Down by Law

Jim Jarmusch's timeless neo-noir fairytale – and how it augured 'Only Lovers Left Alive'

Jim Jarmusch's Down by Law is back in British cinemas 28 years after it joined Spike Lee's She's Gotta Have It and Lizzie Borden's Working Girls in galvanising the embryonic American indie movement.

The original catalyst was Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise (1984), an affectless account of a young Hungarian visitor (Eszter Balint) to Manhattan who short-circuits the hostility of her downtown slacker cousin (John Lurie) on their road trip with his friendlier gambling buddy (Richard Edson). The writer-director's second film, it led critics to re-mint words like "deadpan", "laconic", and "minimalist" in characterising Jarmusch's unhurried, ultra-cool aesthetic.

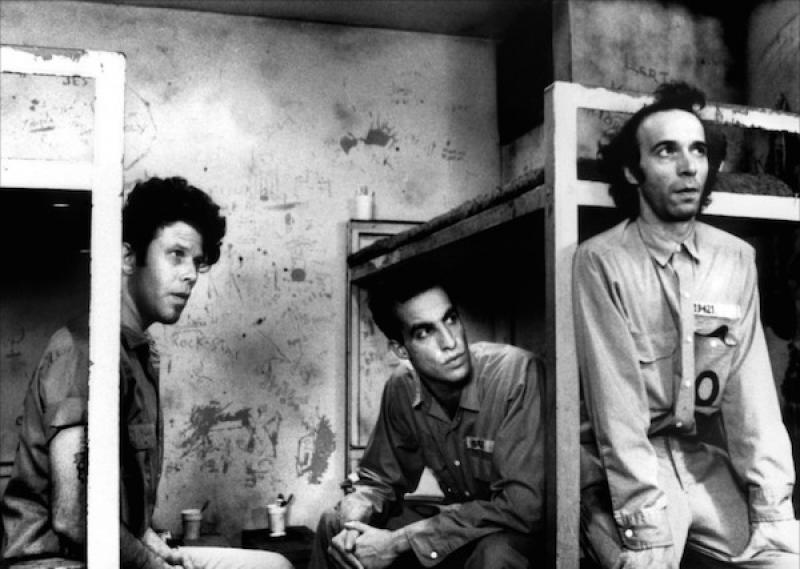

Stranger Than Paradise's story, such as it was, also anticipated that of the more poetic and eventful Down by Law, which depicts the slowly evolving friendship of three ill-sorted convicts. The feckless D.J. Zack (Tom Waits) and the louche pimp Jack (Lurie) – avatars of cool, in denial about their chronic loserdom and failures as lovers and providers – are duped into committing crimes. They wind up in a New Orleans prison where, as rivals in feeble macho braggadoccio, they routinely antagonise each other.

However, Jack's need for conversation elicits Zack's admission that he is late-night radio's Lee "Baby" Sims, whose purring jive talk impresses his cellmate. They unite in aloofness when the garrulous Italian immigrant Bob (Roberto Benigni), way beneath their contempt, is forced upon them. Yet Bob's gregariousness loosens up Jack and Zack, so much so that the three rouse their fellow inmates by stomping in a circle as they chant a refrain from a 1920s novelty song. The soulful lttle man additionally shocks these bogus hardcases with the enormity of his accidental crime, which he matter-of-factly describes to them in his pidgin English, a constant source of hilarity.

It is also Bob, the supposed fool, who shows "my friends, Jack and Zack" how they can break out of jail, and who feeds them with roasted wild rabbit when the trio gets lost in the Louisiana bayou (pictured right). In one moving scene, which milks Benigni's Norman Wisdom-like pathos, the least sentimental of Bob's companions feels obliged to rescue him from imminent recapture. When Jarmusch eases his neo-noir comedy into a fairytale late on, Roberto even shows Jack and Zack how to treat a woman (in this case played by Nicoletta Braschi) and win her devotion. Like Balint's Eva, and like Tilda Swinton's Eve in this year's Only Lovers Left Alive, Bob exemplifies the Jarmuschian outsider who perceives more about a lifestyle than the solipsists who are living it.

It is also Bob, the supposed fool, who shows "my friends, Jack and Zack" how they can break out of jail, and who feeds them with roasted wild rabbit when the trio gets lost in the Louisiana bayou (pictured right). In one moving scene, which milks Benigni's Norman Wisdom-like pathos, the least sentimental of Bob's companions feels obliged to rescue him from imminent recapture. When Jarmusch eases his neo-noir comedy into a fairytale late on, Roberto even shows Jack and Zack how to treat a woman (in this case played by Nicoletta Braschi) and win her devotion. Like Balint's Eva, and like Tilda Swinton's Eve in this year's Only Lovers Left Alive, Bob exemplifies the Jarmuschian outsider who perceives more about a lifestyle than the solipsists who are living it.

Down by Law introduced English-speaking audiences to Benigni and Braschi (pictured below) in a film infinitely less mawkish than would be their 1997 Oscar-winning Holocaust tale Life Is Beautiful. Roberto announces himself by bellowing "Ees a sad and beautiful world" at the sozzled Zack, disrupting the movie's melancholy and its bluesy groove (it presumably gave Benigni a future title). This signalled that Jarmusch doesn't take his hipsters so seriously that a noisy troublemaker can't rattle them. Eve and her equally cool and undead husband, the drone rocker Adam (Tom Hiddleston), are forced to leave his modern-day Detroit hideaway because of the misbehaviour of her bloodsucking brat of a sybarite sister (Mia Wasikowska), not that she's as remotely sympathetic as Bob.

Jarmusch went further with Only Lovers than he had done in his previous movies in making cultural and historical allusions. He drew them into his most polemical film yet about the state of society and its ruinous effect on the planet, as encapsulated by the suicidal Adam's bitter condemnation of careless, wasteful "zombies" (non-vampires). Though the film's Tangier sequences almost have an Anytime ambience, Adam's colloquys with Eve, and the nocturnal glimpses of Detroit's 21st-century dystopia – as well as an admiring glimpse of "Jack White's old house" – root the film in the here and now, which it constantly undercuts through the couple's affectionate nostalgia (or disdain) for the literary and musical celebs they knew in past centuries.

A similar kind of metaphysical time-slippage underpins other Jarmusch films. The Memphis of Mystery Train (1989) is haunted by the unseen spirits of 1930s blues legends and the visible ghost of Elvis. The Old West of Dead Man (1995), blighted by "dark satanic mills" that anticipate Only Lovers' desolate auto factories, is wandered by a doomed greenhorn, William Blake (Johnny Depp), who's taken to to be a reincarnation of the poet by a Plains Indian fond of the Romantics. Broken Flowers (2005) is anchored to the post-Silicon Valley boom but recalls a partially regretful Don Juan's serial amatory pasts. Jarmusch's existential hitman fantasies Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) and The Limits of Control (2009) are not so much timeless films as journeys into postmodern abstraction.

A similar kind of metaphysical time-slippage underpins other Jarmusch films. The Memphis of Mystery Train (1989) is haunted by the unseen spirits of 1930s blues legends and the visible ghost of Elvis. The Old West of Dead Man (1995), blighted by "dark satanic mills" that anticipate Only Lovers' desolate auto factories, is wandered by a doomed greenhorn, William Blake (Johnny Depp), who's taken to to be a reincarnation of the poet by a Plains Indian fond of the Romantics. Broken Flowers (2005) is anchored to the post-Silicon Valley boom but recalls a partially regretful Don Juan's serial amatory pasts. Jarmusch's existential hitman fantasies Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999) and The Limits of Control (2009) are not so much timeless films as journeys into postmodern abstraction.

Down by Law both inscribes and transcends the 1980s. The cinematographer Robby Müller's indelible pre-credit sequence, scored to Waits's chugging "Jockey Full of Bourbon", begins with an autumnal image of a hearse parked by a cemetery. Then a montage of travelling shots, which pause to drop in on Zack and Jack and their sad waking girlfriends (Ellen Barkin, Billie Neal), displays rows of cheap wood-frame houses, poor black neighbourhoods, shacks on the Mississippi, ornate properties in New Orleans and the lacy iron balustrades of its French Quarter, a police shakedown in a rundown district, a schoolyard, and tracts of wasteland. But for the vast cars, left over from the 1970s, the street signage, and modern industrial eyesores, this could be the Depression.

Müller's subsequent shots of empty, detritus-strewn streets at night now conjure post-Katrina New Orleans. Such eerie urban vistas and views of the primordial bayou are coincidentally echoed in Godfrey Reggio's wordless non-fiction film Visitors (2013), which fleetingly shows Katrina-ravaged buildings as it implicates technology in climate disturbance. That's not to say Jarmusch's little classic was prophetic, only that it's timeless, in its modest way, as a resonator of history collapsing into itself. It's also timeless as a lasting joy, albeit one with an undertow of bleakness.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Anemone review - searching for Daniel Day-Lewis

The actor resurfaces in a moody, assured film about a man lost in a wood

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Relay review - the method man

Riz Ahmed and Lily James soulfully connect in a sly, lean corporate whistleblowing thriller

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Comments

great article. As someone