10 Questions for Conductor Vladimir Jurowski | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Conductor Vladimir Jurowski

10 Questions for Conductor Vladimir Jurowski

LPO maestro on the ins and outs of Rachmaninov, focus of this season's celebration

The Russian conductor Vladimir Jurowski, chief conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, heads its major new series devoted to the music of Sergei Rachmaninov, in context with his forerunners and successors.

Here Jurowski tells theartsdesk about the thinking behind the series; why there is never a bad time to celebrate great music; and why he believes Rachmaninov, supposedly the creator of great, soaring melodies, in fact did not write tunes at all.

JESSICA DUCHEN: Vladimir, why this huge celebration of Rachmaninov and why now? What are the motivating forces of this series?

VLADIMIR JUROWSKI: There’s never a specifically good or bad time to celebrate a great composer. The only problem is that if you celebrate him or her at the same time everybody else does, you are likely to be one of many, so all the 100th and 150th celebrations usually make up a perfunctory event. But if you simply feel this is a good time to explore a certain composer, then it usually is; and with Rachmaninov it’s probably now, after we’ve been through last year’s festival at the Southbank Centre, The Rest is Noise, which gave us the chance to play so much 20th-century music in one go. Some Rachmaninov was included in that, but only the usual suspects such as the Second Symphony and one piano concerto.

His music is never about the cosmos, or nature, or the urban world of machines; it’s always the the human beingI’ve always felt that it’s particularly gratifying to look at composers’ oeuvres a) in chronological sequence and b) in connection with works by other composers who have inspired them, or whom they have inspired in return. Having been also through a very detailed exploration of Prokofiev and Britten, to name but a few, over the last several years, I thought Rachmaninov would actually benefit from this type of exploration. We have set him next to people who obviously made him as a composer – Tchaikovsky and Taneyev, or his Russian contemporaries such as Scriabin, for instance – and the big influences from the West like Wagner and Richard Strauss. Then we look at the people with whom he was composing simultaneously: Szymanowski, Enescu, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, et al.

What about that other great symphonist of the era, Sibelius?

At first there was also an idea to involve Sibelius because, for me, Rachmaninov, like Sibelius, and in many ways like Richard Strauss, was one composer who consciously decided not to go in the same direction as everybody else, but to develop his own style and, though modernising it mildly, still remain true to what his outset had been [i.e., they did not abandon their traditional and melodic leanings to pursue serialism or atonality]. In the end, though, I think the reason we didn’t include Sibelius was because there’s been a cycle very recently and we didn’t want to do too much of the same thing.

Those other composers will be featured, though, and I think there are several unusual aspects to this. One is that we are putting Rachmaninov into some kind of context. The second is that there will be a lot of less performed or underperformed works such as the opera The Miserly Knight (Sergei Leiferkus pictured above in the Glyndebourne production conducted by Jurowski) the choral works such as the Cantata Spring, or the Three Russian Songs for choir and orchestra.

Those other composers will be featured, though, and I think there are several unusual aspects to this. One is that we are putting Rachmaninov into some kind of context. The second is that there will be a lot of less performed or underperformed works such as the opera The Miserly Knight (Sergei Leiferkus pictured above in the Glyndebourne production conducted by Jurowski) the choral works such as the Cantata Spring, or the Three Russian Songs for choir and orchestra.

Then the other aspect is that we will also show some of the works in compositional progress, as they were created. The piano concertos will come in all available versions – that’s quite unusual. For the First and Fourth Piano Concertos, at least two versions of each exist, and in the case of the Fourth there are even three, but I don’t think the first one is available; all we’ve got is its second version, from the 1920s, and the third of the 1940s, which was made with final corrections after the piece had already been released and recorded. And we’re also including some orchestrations of Rachmaninov’s piano works and songs.

When we started planning this, I wanted to have given all Rachmaninov works, including the three operas – indeed, three and a half, because there’s his unfinished opera, Monna Vanna – and all the choir a cappella works, but it would have been too ambitious for an institution like the LPO, which simply wouldn’t have had the funds to do this on our own. That’s why we decided to limit ourselves to all the core works: three symphonies, several important symphonic pieces, all the piano concertos in all the versions, plus the arrangements, plus the opera.

Even if you’ve had to scale down your initial vision, that’s still an extremely hefty festival. What aspects do you find most exciting?

I don’t think it’s going to be monotonous, because there will only be two concerts where Rachmaninov’s music is played on its own – the galas, so to speak. All the other concerts will include music by other composers – and sometimes the connections will be really inspiring. We have, for instance, The Miserly Knight played side by side with fragments from Das Rheingold; and George Enescu’s massive Third Symphony, a very rarely performed and I think greatly underrated work, will be performed alongside Rachmaninov’s Three Russian Songs and Spring.

Do you think Rachmaninov has perhaps been seriously misunderstood across previous decades?

Do you think Rachmaninov has perhaps been seriously misunderstood across previous decades?

Yes! Especially during his lifetime, there was a massive misunderstanding that he was chiefly a piano virtuoso; then the public and critical view basically downgraded him to some kind of Hollywood sentimental composer, which he wasn’t. I think the problem with Rachmaninov was his conscious choice to remain true to the principles that he followed from his youth. As I said, there were other composers who chose the same path: Richard Strauss, who turned away from modern music after Elektra and consciously chose to go into a much milder direction; and the other one was Sibelius, who I don’t think ever considered public success as an indicator of where his talent should go; but he still remained largely caught in the late 19th century – or rather, in a very individual style which certainly included some inflections of the 20th century, but was chiefly late Romantic.

And so it’s the same with Rachmaninov: his idiom is specifically personal. You can always tell his music from the others’ after only a few bars, even in such a complex and difficult work as the Piano Concerto No 4, which is very dear to my heart and will certainly be included in the celebrations in both versions. I think that was a very good example of the way he searched, almost until his dying day, for the perfect realisation of his vision. That’s a work that owes very much to his life in the West, and it is a 20th-century work. You can hear elements in it that are very Stravinskian, or that recall Ravel and even Gershwin – and yet there is not a single note in there which is not deeply, personally Rachmaninovian.

What would you say his central preoccupation is, if it’s possible to pinpoint one, across his oeuvre?

There’s one interesting aspect that I remember reading about in a Russian analysis of Rachmaninov’s work: at the centre point of his attention there is always the human being. His music is never about the cosmos, or nature, or the urban world of machines; it’s always the the human being, about human emotions, human life, human burden, human suffering, human joys. This humanitarian aspect of his work is rather remarkable in a time when human life often appeared to be worth very little and when beauty was certainly not celebrated on a daily basis in art and music. Yet he is someone who remains stubbornly obsessed with all those topics.

Therefore I think now is probably the time to revisit Rachmaninov without preconceptions, and just take him for what he was, with all his strengths and weaknesses. I think those who have ears to hear will recognise Rachmaninov not only as a creator of very popular melodies, but also as a great craftsman. That’s the other aspect I’m hoping to bring to people’s attention, simply through playing his music in certain contexts.

Of course there are certain aspects of his music which some may moan about as not being adventurous enough, not particularly radical, maybe not always as inventive as one would wish, but it has other fine qualities of its own. It’s always first-rate music, by all standards.

It is astonishing to read about Rachmaninov’s training at the Moscow Conservatoire. The depth of study that he and his contemporary Alexander Scriabin were put through with counterpoint exercises, and so forth, was extremely rigorous, intense and uncompromising. They were taught the building-blocks of their art in an incredibly thorough way, yet often the sheer quality of their craftsmanship is not well enough recognised. I suppose the film Brief Encounter has a lot to answer for, wonderful though it is and much as I love it. People often automatically dismiss Rachmaninov as emotional, therefore sentimental and therefore no good – yet there’s absolutely no reason why music full of emotion can’t be well written. It seems to have been very difficult to get this message across.

There’s one other thing that people, especially here in the West, don’t understand or don’t know: what often is seen as a melodic inflection is in fact not melody at all. I think it’s a myth that Rachmaninov was a great melodist. He was, to me, the opposite of a great tune writer. He used very ascetic and spare church mode tunes from the Orthodox service. If anything, I believe that Rachmaninov was a proto-Minimalist – in the same way that Carl Orff was.

Tell us more. In what sense?

In the sense that he minimalised the tools and the materials with which he was working – they were used with austerity. The only things he used in abundance were harmonic and polyphonic means, but melodically speaking all his music is created from two, three or four notes. Look at the opening of the the Third Piano Concerto – I think this is a good example. It’s not a melody! It’s the same four notes played in a different order. But at the same time it becomes a melody.

That’s fascinating. So many of us usually think of Rachmaninov in terms of great, soaring melodies…yet you’re saying that’s not him at all?

Those melodies never exceed the span of a fourth. And if you play it slowly, it sounds like a church tune – which it is.

I think this would also tie very much to the impression one receives from his own piano recordings. Hear Rachmaninov play his own works and you realise it is anything but heart-on-sleeve; indeed, his playing is very cool and detached, isn’t it?

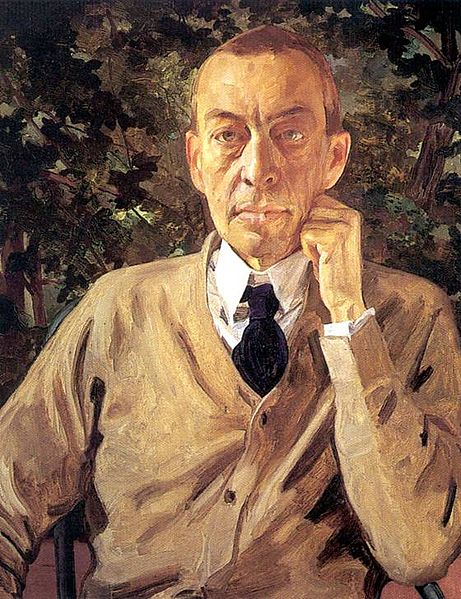

That was very much his approach to music in general: highly academic and very composed, almost withdrawn. He was never flamboyant, or outgoing (rare picture right of Rachmaninov smiling, with daughter and dog at Ivanovka in 1910), or trying to please. I think if you play his music this way, but obviously with a lot of inner understanding and feeling, then it speaks for itself much better.

That was very much his approach to music in general: highly academic and very composed, almost withdrawn. He was never flamboyant, or outgoing (rare picture right of Rachmaninov smiling, with daughter and dog at Ivanovka in 1910), or trying to please. I think if you play his music this way, but obviously with a lot of inner understanding and feeling, then it speaks for itself much better.

It’s very interesting that when there are preconceptions about a composer like Rachmaninov, people might come along – musicians included – with the idea that this is emotional, over the top, sentimental, "Hollywood" music; then they play it that way, too, because they believe it’s how it is supposed to sound; and thus the myths are reinforced. Yet it’s a false tradition - it has nothing to do with the reality of the works themselves. Do you think we might come out of your series with a rather different impression of what Rachmaninov is really all about?

I always say that people who have ears will hear, and people who have no ears will remain with their preconceptions. I am certainly not hoping to convert those individuals, but to give the other ones who have ears a chance to evaluate something anew. I spoke about Rachmaninov being a proto-Minimalist; there’s a very good work recently written by the Russian post-Minimalist composer, Anton Batagov, who is also a brilliant pianist. He entitled one of his works, a piano cycle, Selected Letters of Sergei Rachmaninov – it is a series of post-Minimalist compositions and each piece is an imaginary musical letter from Rachmaninov to composers of the late 20th and early 21st century, such as Philip Glass, Peter Gabriel, Arvo Pärt, Ludovico Einaudi, etc. It’s all based on the B minor piece from Rachmaninov’s Moments Musicaux [Op.16 No.3]; he’s basically showing that this work triggered the development of Minimal and post-Minimal music. There will be no Minimalist music in our programmes, but if I do manage to get Anton Batagov over to London to do maybe just a pre- or post-concert performance, just once, I think this alone would answer quite a lot of questions about Rachmaninov’s connection to our own time.

And so, in a way, Rachmaninov, having been the arrière-gardist his entire life, and always perceived as such by so many musical people, suddenly shifts into the forefront of musical thinking and becomes the troubadour of the post avant-garde epoch – which is quite an interesting thought.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment